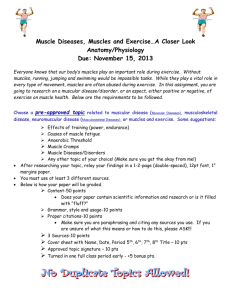

Exercising with a Muscle Disease

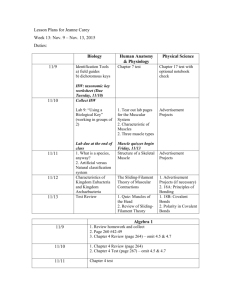

advertisement