Oct27 SeversonScreen.. - UW Faculty Web Server

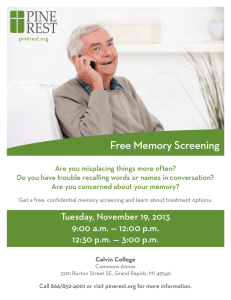

advertisement