Excellent long-term reproducibility of the

advertisement

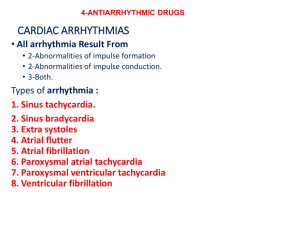

Excellent Long-Term Reproducibility of the Electrophysiologic Efficacy of Quinidine in Patients with Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation and Brugada Syndrome BERNARD BELHASSEN, M.D., AHARON GLICK, M.D., and SAMI VISKIN, M.D. From the Department of Cardiology, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel-Aviv, Israel, and Sackler School of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel Background: Quinidine is very effective in preventing the reinduction of sustained ventricular fibrillation (VF) during electrophysiologic study (EPS) in patients with idiopathic VF and Brugada syndrome. However, there are no data on the long-term reproducibility of this EP efficacy. Methods and Results: Nine patients (seven males and two females, aged 21–72 years), who suffered from aborted cardiac arrest (n = 8) or recurrent syncope (n = 1) due to Brugada syndrome (n = 5) or idiopathic VF (n = 4), comprised the study. All patients had inducible sustained VF at baseline that was prevented by quinidine therapy and underwent another EPS on medication after 1.7–23.6 (9.8 ± 6.8) years (>5 years in eight patients). Two patients underwent two late EPS on quinidine. The goal of repeat EPS on quinidine was to ensure persistent long-term drug efficacy (n = 6) or to elucidate the reason of syncopal episodes during therapy (n = 3). The EPS protocol significantly evolved over the years as it became more aggressive (more pacing sites and/or more ventricular extrastimuli). All nine patients tolerated the medication well and had no recurrent documented arrhythmic events during long-term follow-up (mean 15 ± 7 years). No sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias could be induced in any patient during repeat late EPS. In six patients, a more aggressive stimulation protocol could be tested at repeat EPS. Conclusion: The long-term reproducibility of the EP efficacy of quinidine in patients with idiopathic VF and Brugada syndrome is excellent. EP-guided quinidine therapy represents a valuable long-term alternative to ICD therapy in these patients. (PACE 2009; 32:294–301) quinidine, electrophysiologic study, programmed ventricular stimulation, idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, Brugada syndrome Introduction Implantation of an automatic cardioverterdefibrillator (ICD) is recommended by most cardiac electrophysiologists worldwide in patients with ventricular fibrillation (VF) occurring in patients without organic heart disease (idiopathic VF) and those affected with the Brugada syndrome.1,2 Antiarrhythmic therapy with quinidine is frequently used as an adjuvant to control recurrent ventricular arrhythmias in implanted patients.3,4 The policy at our institution during the last three decades concerning these patients has been different and based on our published experience5–7 showing: (1) the great efficacy of quinidine in preventing reinduction of sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias during electrophysiology study (EPS), and (2) the excellent long-term clinical out- No disclosure. Address for reprints: Bernard Belhassen, M.D., Department of Cardiology, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Weizman Street 6, Tel-Aviv 64239, Israel. Fax: +00-972-3-697-4418; e-mail: bblhass@tasmc.health.gov.il Received April 28, 2008; revised August 4, 2008; accepted September 18, 2008. come of the patients treated with the drug. Thus, we usually have left the patient the choice between implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy and EP-guided chronic quinidine therapy.8 However, there is only scarce information available about the long-term EP efficacy of quinidine. In this study, we review our experience on the long-term EP efficacy of quinidine in a group of patients who underwent EP-guided quinidine therapy for idiopathic malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Methods Patient Selection Records of all patients with inducible sustained VF during EPS were reviewed. Criteria for inclusion in the study included all the following: (1) no recognizable heart disease based on normal findings during noninvasive (echocardiogram, exercise test, Thallium test) and/or invasive (right and left ventriculography and coronary angiography) evaluation, (2) normal baseline QT interval on repeated electrocardiograms (ECGs), (3) EP testing with quinidine showing no inducible sustained ventricular arrhythmias, (4) long-term treatment with quinidine following the initial C 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. C 2009, The Authors. Journal compilation 294 March 2009 PACE, Vol. 32 PACE, Vol. 32 M 28 M 52 F 24 M 27 M 40 M 21 M 43 F 51 M 72 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Abbreviations: A = age; BL = blood level (mg/L); BS = Brugada syndrome; F = female; IVF = idiopathic ventricular fibrillation; NI = noninducible; M = male; NA = nonavailable; NSVT = nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; Pt = patient; S = sex; * = quinidine hydrochloride. NSVT(24) NSVT(7) 2.5 3.2 1,500 1,500 13/6/02 16/2/06 NSVT(7) NI NSVT(60) NI NSVT(34) NSVT(15) NSVT(14) NI NI 2.57 NA NA 3.8 1.5 NA 2.9 1.2 NA 1,500 1,500 1,500 1,500 1,500 1,500 1,500 600* 750 7/11/02 14/7/92 3/9/02 11/7/95 13/2/99 13/7/99 23/11/99 23/10/07 24/5/05 NI NI NSVT(7) NI NI NSVT(9) NI NI NSVT(17) 2.0 5.2 2.3 3.8 2.6 3.9 4.5 6.2 1.29 1,500 1,500 1,500 1,500 1,500 1,500 1,500 1,500 750 5/4/79 22/11/81 27/2/85 16/11/87 4/2/92 31/7/94 22/11/94 2/12/97 23/9/03 Results BL Dose Date Diagnosis IVF VF + BS VF + BS IVF IVF VF + BS VF + BS IVF Syncope + BS Results BL Dose Date BL Dose Quinidine Bisulphate Quinidine Bisulphate Date EPS No. 2 Results March 2009 S/A The study group comprised nine patients, seven males and two females, ranging in age from 21 to 72 (40 ± 16.5) years (Table 1). Five patients Pt Results Study Patients (Table I) EPS No. 1 Definitions Sustained VF was a ventricular tachyarrhythmia manifesting a continuously varying morphology with a mean cycle length <200 ms that required cardioversion for termination or resulted in clinical cardiac arrest before spontaneous termination. Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) was a tachycardia of ≥6 complexes that was shorter than 30 seconds in duration and was not associated with loss of consciousness. Arrhythmias were “noninducible” when <6 repetitive ventricular complexes were induced. Results of Electrophysiological Drug Testing in Nine Patients Table I. EPS Protocol EPSs were performed using a protocol of programmed ventricular stimulation (PVS) that evolved over the years. From 1979 to 1982, PVS was performed only from the right ventricular apex, using three basic cycle lengths (600, 500, and 400 ms) and a maximum of two extrastimuli. In 1983, pacing from the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) was added and the number of basic cycle lengths was decreased to two (usually 600 and 400 ms). The use of triple extrastimulation in our laboratory was introduced in 1988. In addition, our protocol has included repetition (10 times) of double extrastimulation (since 1979) and repetition (five times) of triple extrastimulation (since 1988) both at the shortest coupling intervals. This was done at each pacing site and for each of the cycle lengths tested. We previously found that repetition of extrastimulation increases the sensitivity of PVS protocols.11 The stimulus current intensity was set at five times the diastolic threshold (but never >3 mA). EPS No. 3 drug testing, and (5) repeat EP testing on quinidine ≥1 year following the first drug study. From February 1979 to December 2007, 76 patients (87% males, 38% with spontaneous VF) with inducible VF and no obvious heart disease underwent repeat EP testing with quinidine in our laboratory. In 71 (93.4%) of these patients, quinidine bisulphate (750–2,000 mg/day) effectively prevented the reinduction of sustained ventricular arrhythmias. Nine (12.6%) of the 71 patients underwent repeat EPS on quinidine >1 year after the initial drug testing and comprised the study group. The case report of one of the patients has been reported elsewhere.9,10 All the study patients were included in our previous publications.5–7 Quinidine Bisulphate QUINIDINE FOR IDIOPATHIC VF AND BRUGADA SYNDROME 295 BELHASSEN, ET AL. Figure 1. ECG tracings obtained at hospital admission (November 24, 1997) of a 57-year-old woman with a history of multiple syncopes (no. 10) during the few weeks prior to admission. Ventricular extrasystoles of variable coupling interval (some of them very short coupled) are seen in panel A. Panel B shows an episode of rapid nonsustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, triggered by a very short coupled ventricular extrasystole. In panel C, a similar long-lasting episode resulting in syncope is shown. In all nine patients who had inducible sustained VF at baseline, no sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias could be induced during treatment with quinidine bisulfate (Quiniduran,* Teva Laboratories, Tivka, Israel) at doses ranging from 750 mg (one patient) to 1,500 mg (eight patients) (Figs. 2 and 3). The effective quinidine serum blood levels ranged from 1.3 to 6.2 mg/L (mean 3.5 ± 1.6 mg/L). In six of these nine patients, no significant arrhythmias were induced while asymptomatic NSVT including 7–17 beats was induced in the remaining three patients. ride quinidine (Serecor,* Sanofi-Aventis Laboratories, Paris, France) due to discontinuation of the production of quinidine bisulphate.12 In seven of the eight patients who underwent initial and repeat EPS on the same quinidine salt, an identical drug dosage of 1,500 mg/day was tested. In five patients, the serum quinidine levels obtained at the initial and repeat EPS were 3.82 ± 1.65 and 2.39 ± 1.05 mg/L, respectively (P = 0.14 using paired Wilcoxon signed-ranks test). No sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias could be induced in any of the nine patients during repeat EP testing on quinidine (Figs. 4 and 5). This was observed despite the fact that in four of the nine patients, the PVS protocol was more aggressive at repeat study (triple extrastimulation could be tested at repeat EPS while only double extrastimulation was applied at the initial EPS). Repeat EPS on Quinidine (Table I) Repeat EP study was performed in all nine patients after 1.7–23.6 (9.8 ± 6.8) years of quinidine therapy (≥5 years in eight of nine patients). The goal of the repeat EPS on quinidine was to ensure persistent long-term drug efficacy (n = 7 patients) or to elucidate the reason of syncopal episodes during therapy (n = 2; patients 5 and 9). In all patients but one, the repeat drug study was performed on the same quinidine salt (bisulphate). In one patient the EPS was performed on hydrochlo- Third EPS on Quinidine (Table I) In two of the nine patients (patients 6 and 7), a third EPS was performed during quinidine therapy 3 years and 6 years, respectively, after the second drug study. In patient 7 it was performed to reassess drug efficacy while in patient 6 it was justified by the occurrence of a syncopal episode during quinidine therapy. In both patients, only NSVT could be induced. (one female) had Brugada syndrome and four patients had idiopathic VF. Eight patients had cardiac arrest with documented VF (Fig. 1) and one patient with the Brugada syndrome had recurrent syncope of unknown cause. Initial EPS on Quinidine (Table I) 296 March 2009 PACE, Vol. 32 QUINIDINE FOR IDIOPATHIC VF AND BRUGADA SYNDROME Figure 2. Baseline electrophysiologic study (November 25, 1997). Induction of sustained rapid polymorphic ventricular tachycardia with triple extrastimulation from the right ventricular apex. The tachycardia was terminated with DC shock. Clinical Course All nine patients tolerated the medication well during long term and had no recurrent documented arrhythmic events during follow-up ranging from 4.5 to 29 (mean 15 ± 7) years. However, an ICD was implanted in two patients (patients 3 and 6). Patient 3 was 24 years old at the time of initial cardiac arrest. After 17 uneventful years of quinidine therapy, she opted for the ICD option (of note, this patient had two uneventful pregnancies and normal childbirth during quinidine therapy). Patient 6 initially presented with a history of recurrent syncope and had documented VF at the emergency room. He remained asymptomatic for 8 years on 1,500-mg quinidine (which was found effective at two EP studies performed 5 years apart) but later had unexplained syncope that prompted a third EP study on quinidine. Although this study only showed the induction of a 4-second episode of NSVT, it could not be ruled out that that the syncopal episode was due to a spontaneous longer episode of NSVT. Therefore, an ICD was implanted without discontinuing PACE, Vol. 32 quinidine therapy. Three months and 1 year later, the patient had recurrent syncope but ICD interrogation failed to reveal any arrhythmia in both instances. One patient (no. 2) who had normal coronary angiography in 1981 at the time of his cardiac arrest underwent coronary artery bypass grafting for multivessel disease with preserved left ventricular function 18 years later. All remaining eight patients had no change in their cardiac status during follow-up. Discussion Efficacy of Quinidine In contrast to the present general skepticism of the cardiologic community toward the use of class 1 antiarrhythmic drugs and especially quinidine in patients with ventricular arrhythmias, the literature has shown the extraordinary efficacy of this drug in the treatment of malignant arrhythmias occurring in patients with no demonstrable heart disease. The first patients with idiopathic VF reported, back in 1929 and 1949, were March 2009 297 BELHASSEN, ET AL. Figure 3. Repeat electrophysiologic study after 1 week of treatment with quinidine bisulfate (1,500 mg/day). No ventricular arrhythmias could be induced with up to five extrastimuli delivered from both the right ventricular apex and the right ventricular outflow tract. treated with quinidine after multiple episodes of spontaneous polymorphic VT and VF were clearly documented.13,14 Both patients had an excellent response to the medication. Interestingly, a second publication reporting the long-term follow-up of the patient initially reported in 1949 established that this patient eventually died of cancer at old age, without ever experiencing a recurrence of his arrhythmia while on quinidine therapy for 40 years.15 In addition, quinidine is being successfully used as a first-line therapy for abolishing arrhythmic storms in patients with Brugada syndrome.3,4 Our group reported the first largest series of patients with idiopathic VF or Brugada syndrome in whom quinidine was found to be very effective (96%) in preventing VF reinducibility during EPS.6 Similar results were found by others.16–21 In this study, we report the first series of nine pa- 298 tients with inducible VF in whom the repeat EP efficacy of quinidine was confirmed late (>5 years in eight patients) following the initial drug testing. In patients with Brugada syndrome, the efficacy of quinidine has been attributed to various mechanisms: (1) strong inhibition of Ito current that restores electrical homogeneity and abolishes phase 2 reentry,2 and (2) anticholinergic effects. In patients with idiopathic VF, the mechanism of the efficacy of quinidine is much obscure.6 Effect of Stimulation Protocol Our study has spread over three decades, and major changes in the stimulation protocol occurred during this period. Therefore, one could wonder whether the use of more aggressive PVS protocols at repeat drug study would March 2009 PACE, Vol. 32 QUINIDINE FOR IDIOPATHIC VF AND BRUGADA SYNDROME Figure 4. Repeat electrophysiologic study performed approximately 10 years later during treatment with quinidine hydrochloride (600 mg/day). Only single repetitive ventricular complexes are induced with triple extrastimulation from the right ventricular apex. have revealed drug failure among some patients studied earlier with less aggressive protocols. The results of our study showed that this was not the case. All four patients in whom drug efficacy was first tested with double extrastimulation and who were subsequently tested with more aggressive PVS protocols showed a similar efficacy of quinidine. Figure 5. Same findings as in Figure 4 during programmed ventricular stimulation from the right ventricular outflow tact. PACE, Vol. 32 March 2009 299 BELHASSEN, ET AL. Study Limitations Following the first drug study, eight of our nine patients did not develop any change in their cardiac condition during follow-up as expected from the fact they had no obvious heart disease at study inclusion. However, one patient subsequently developed significant coronary artery disease with preserved left ventricular function. Had this patient suffered an acute myocardial infarction during quinidine therapy it might have altered the later EP results. Therefore, close patient follow-up is necessary in order to detect any change in cardiac status or other abnormalities (such as electrolyte disturbances) that may affect the safety of long-term quinidine therapy. Clinical Implications The results of our study suggest that EPguided therapy with quinidine is a very reasonable long-term therapeutic alternative to ICD therapy for patients with idiopathic VF or Brugada syndrome provided several conditions are fulfilled: (1) the patients have inducible VF at baseline EPS, (2) quinidine prevents the reinduction of VF, (3) the patients exhibit a good tolerance to the medication, (4) repeated assertion of drug compliance during follow-up is obtained, (5) the patients are committed to a life-long drug therapy, and (6) no significant change in cardiac status occurs during follow-up. Such a therapeutic option can be safely recommended to patients who refuse the implantation of an ICD or to patients for whom cost constraints resulting from implantation and replacements of ICD over the years will make impossible the ICD option. Other potential candidates are young patients in whom multiple ICD replacements are expected during long term as well as patients in whom ICD needs to be explanted due to complications. Finally, our results suggest that patients with Brugada syndrome and inducible VF, but no previous cardiac arrest, and in whom controversial results presently exist concerning the predictive value of EPS,22,23 may benefit from the quinidine option rather than ICD therapy, taking in account the high incidence of complications observed with ICD, some of them potentially lethal.24 References 1. Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, Buxton AE, Chaitman B, Fromer M, Gregoratos G, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48:e247–e346. 2. Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D, Gussak I, et al. Brugada syndrome: Report of the second consensus conference: Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation 2005; 111:659–670. 3. Marquez MF, Salica G, Hermosillo AG, Pastelin G, Gomes-Flores J, Nava S. Ionic basis of pharmacological therapy in Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2007; 18:234–240. 4. Ohgo T, Okamura H, Noda T, Satomi K, Suyama K, Kurita D. Acute and chronic management in patients with Brugada syndrome associated with electrical storm of ventricular fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2007; 4:695–700. 5. Belhassen B, Shapira I, Shoshani D, Paredes A, Miller H, Laniado S. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation: Inducibility and beneficial effects of class I antiarrhythmic agents. Circulation 1987; 75:809– 816. 6. Belhassen B, Viskin S, Fish R, Glick A, Setbon I, Eldar M. Effects of electrophysiologic-guided therapy with class 1A antiarrhythmic drugs on long-term outcome in patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and the Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1999; 10:1301–1312. 7. Belhassen B, Glick A, Viskin S. Efficacy of quinidine in highrisk patients with Brugada syndrome. Circulation 2004; 110:1731– 1737. 8. Belhassen B, Viskin S, Antzelevitch C. The Brugada syndrome: Is an implantable cardioverter defibrillator the only therapeutic option? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2002; 25:1634–1640. 9. Belhassen B, Pelleg A, Miller HI, Laniado S. Serial electrophysiological studies in a young patient with recurrent ventricular fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1981; 4:92–99. 10. Belhassen B. A 25-year control of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation with electrophysiologic-guided antiarrhythmic drug therapy. Heart Rhythm 2004; 1:352–354. 300 11. Belhassen B, Shapira I, Sheps D, Shoshani D, Laniado S. Programmed ventricular stimulation using up to two extrastimuli and repetition of double extrastimulation for induction of ventricular tachycardia: A new highly sensitive and specific protocol. Am J Cardiol 1990; 65:615–622. 12. Viskin S, Antzelevitch C, Marquez MF, Belhassen B. Quinidine: A valuable medication joins the list of “endangered species.” Europace 2007; 9:1105–1106. 13. Dock W. Transitory ventricular fibrillation as a cause of syncope and its prevention by quinidine sulfate. Am Heart J 1929; 4:709– 714. 14. Moe T. Morgagni-Adams-Stokes attacks caused by transient recurrent ventricular fibrillation in a patient without apparent heart disease. Am Heart J 1949; 37:811–818. 15. Konty F, Dale J. Self-terminating idiopathic ventricular fibrillation presenting as syncope: A 40-year follow-up report. J Intern Med 1990; 227:211–213. 16. Aizawa Y, Naitoh N, Washizuka T, Takahashi K, Uchiyama H, Shiba M, Shibata A. Electrophysiological findings in idiopathic recurrent ventricular fibrillation: Special reference to mode of induction, drug testing and long-term outcomes. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1996; 19:929–939. 17. Wever EFD, Hauer RNW, Oomen A, Peters RHJ, Bakker PFA, Robles de Medina EO. Unfavorable outcome in patients with primary electrical disease who survived an episode of ventricular fibrillation. Circulation 1993; 88:1021–1029. 18. Otto C, Tauxe R, Cobb L, Greene HL, Gross BW, Werner JA, Burroughs RW, et al. Ventricular fibrillation causes sudden death in Southeast Asian immigrants. Ann Intern Med 1984; 100: 45–47. 19. Garg A, Finneran W, Feld GK. Familial sudden cardiac death associated with a terminal QRS abnormality on surface 12-lead electrocardiogram in the index case. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1998; 9:642–647. 20. Hermida JS, Denjoy I, Clerc J, Extramiana F, Jarry G, Milliez P, Guicheney P, et al. Hydroquinidine therapy in Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43:1853–1860. 21. Mizusawa Y, Sakurada H, Nishizaki M, Hiraoka M. Effects of low-dose quinidine on ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with Brugada syndrome: Low-dose quinidine therapy as March 2009 PACE, Vol. 32 QUINIDINE FOR IDIOPATHIC VF AND BRUGADA SYNDROME an adjunctive treatment. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006; 47:359– 364. 22. Paul M, Gerss J, Schultze-Bahr E, Wichter T, Vahlhaus C, Wilde AA, Breithardt G, et al. Role of programmed ventricular stimulation in patients with Brugada syndrome: A meta-analysis of worldwide published data. Eur Heart J 2007; 28:2126–2133. PACE, Vol. 32 23. Viskin S, Rogowski O. Asymptomatic Brugada syndrome: A cardiac ticking time-bomb? Europace 2007; 9:707–710. 24. Rosso R, Glick A, Glikson M, Wagshal A, Swissa M, Rosenhek S, Shetboun I, et al. Outcome after implantation of cardioverter defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: A multicenter Israeli study (ISRABRU). IMAJ 2008; 10:435–439. March 2009 301