II. Teaching Techniques and Procedures

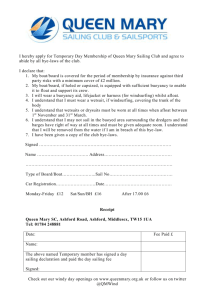

advertisement