CAPACITANCE PURPOSE: There are three objectives in this

advertisement

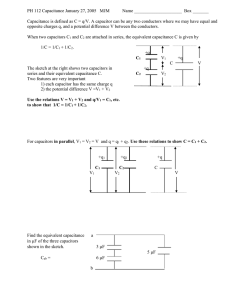

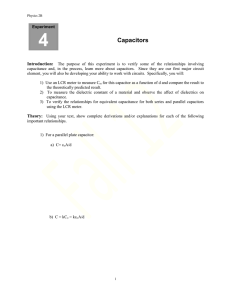

August 7, 2007 CAPACITANCE PURPOSE: There are three objectives in this experiment: to determine the precise values of some commercially available capacitors and hence to check the formulae for combining capacitors in parallel and in series. to investigate how the capacitance of a parallel plate air-dielectric capacitor varies with plate separation. to measure the dielectric constants of several insulating materials. REFERENCES: Introduction to Electrodynamics, 3rd Edition, D. J. Griffiths: p 103 to 106; 183 to 186 Electricity and Magnetism, 3rd Edition, W. J. Duffin: p 108 to 120 University Physics, 11th Edition, Young & Freedman: P 909 to 918; 922 to 928 Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 78th Edition, CRC Press Inc. APPARATUS: 3 commercial capacitors multimeter 3 terminal boards 6 leads parallel plate capacitor 16 paper spacers steel weight calipers/micrometer 2 pieces of acrylic 2 pieces of Styrofoam 6 pieces of Bristol board INTRODUCTION: Capacitors are commonly used in a variety of electric circuits: they are used to tune radio receivers, as filters in power supplies, to eliminate sparking in automobile ignition systems, and as energy storage devices in electronic flash units. In this experiment we will investigate these devices in more detail. When an uncharged finite conductor removed from other objects is given a charge Q, its potential is raised from zero to a certain value V (with respect to zero potential at infinity). The value Q/V is called the capacitance of the conductor, C: C≡ Q V CAPACITANCE-1 [1] August 7, 2007 For example, a spherical charged conductor with charge Q has an electric potential outside the sphere given by: V= Q 4πε o r [2] At the surface, the potential is given by equation [2], substituting r = R, the radius of the sphere. By the definition of capacitance, and a reference position at infinity, the capacitance of an isolated charged sphere is therefore: C= Q Q = = 4πε o R V Q 4πε o R [3] Note that the capacitance of an isolated charged sphere is proportional only to its radius, and is independent of the charge on the sphere. This is true in general: capacitance is an inherent property of the conductor, and depends only on the geometry and the material with which the device is made, with some dependence on environmental factors such as temperature, pressure, humidity, etc.. Typically capacitance is discussed in reference to two conductors carrying charges of equal magnitude and opposite sign. In this scenario, a potential difference, ∆V, exists between the two conductors due to the presence of this charge separation. Equation [1] then becomes: C≡ Q ∆V [4] where Q is the magnitude of the charge on each conductor. Capacitance is a measure of the amount of charge the conductors will hold for a given potential difference, and by definition, capacitance is a positive quantity. The SI unit for capacitance is the Coulomb/Volt or farad, symbol F. In practice, the submultiples µF and pF tend to be more convenient. In this experiment, we will be investigating parallel plate capacitors. These devices consist of two parallel metal plates of equal area A, separated a distance d as shown in figure 1. One plate carries a charge of +Q, the other carries a charge of –Q. Therefore, each plate has a surface charge density of: σ= Q A [5] Assuming that the plates are very close together, in comparison with their length and CAPACITANCE-2 August 7, 2007 width, it can be shown that the electric field between the plates is: r σ E = [6] εo With a uniform electric field, the potential difference between the two plates is then: r σd ∆V = E ⋅ d = εo [7] and by combining equations [7], [5], and [4], the capacitance of the parallel plate device is given by: C= εo A [8] d Again, the capacitance is only dependent on geometric factors: the area of the plates (A) and the distance between them (d). -Q +Q Area = A d Figure 1: Schematic depiction of a parallel plate capacitor. In the preceding discussion, it was assumed that the space between the two conductors was evacuated. This is not always the case; in many devices, a non-conducting material called a dielectric is inserted between the two conductors to increase the capacitance. If the dielectric completely fills the space between the conductors, the capacitance increases by a dimensionless factor κ, which is called the dielectric constant of the material: C = κ Co [9] CAPACITANCE-3 August 7, 2007 where Co denotes the capacitance in the absence of the dielectric. In particular, for a parallel plate capacitor with a dielectric, the capacitance is given by: C =κ εo A d [10] Table 1 summarizes some values of the dielectric constant. Note that these materials all have dielectric constants greater than unity: this implies that the presence of these dielectrics will always serve to increase the inherent capacitance of the devices to which they are added. Table 1: Dielectric constants of various substances (20°C) Vacuum Air Acrylic Bakelite Neoprene Nylon Paper Bristol board Plastic Polyethylene Polystyrene Pyrex glass Silicone oil Styrofoam Teflon Transformer oil Water, distilled 1.00000 1.00059 2.7 – 4.5 4.9 4.0 – 6.7 3.4 1.9 - 3.7 depending on grade 1.8 – 2.0 depending on air content 2.6 - 3.6 depending on type 2.25 - 2.3 2 – 2.8 5.6 2.5 1.03 2.1 22 80 In many applications, more than one capacitor is used in a circuit. It is often therefore useful to be able to calculate the equivalent capacitance between two points such as A and B in the circuit, where the equivalent capacitance is again defined by equation [4]. However, we can now express ∆V as VA – VB, the potential difference resulting from the transference of Q from B to A. In other words, the equivalent capacitance is the capacitance of a single capacitor which, if connected between A and B, would produce the same effect as the original configuration. Determining equivalent capacitance involves two principles: conservation of charge and the path-independence of potential difference. In this experiment we will be investigating two special cases: capacitors in series and capacitors in parallel. CAPACITANCE-4 August 7, 2007 Capacitors in series Figure 2 shows a set of capacitors in series, with the capacitors represented by their circuit diagram symbol: two thick parallel lines of equal length. A B C1 C2 C3 Figure 2: three capacitors in series. When point A is connected to the positive terminal of a battery, and B is connected to the negative terminal of the battery, charge begins to flow. Electrons from C1 flow to the positive terminal, leaving a net +Q on the left-hand plate of C1, while electrons from the battery flow to C3, leaving a net –Q on the right-hand plate of C3. Conservation of charge ensures that the left-hand plate of C1 and the right-hand plate of C3 accumulate charge of equal magnitudes. As negative charge builds up on the right-hand plate of C3, an equivalent amount of negative charge is forced off the left-hand plate of C3, leaving it positively charged. The negative charge leaving the left-hand plate of C3 accumulates on the right-hand plate of C2, and so on. The overall effect is that all the capacitors in series have ±Q on their conducting surfaces, as shown in figure 3. A +Q -Q +Q C1 -Q +Q C2 + -Q B C3 – ∆V Figure 3: Charge distribution among capacitors in series connected across a battery. The potential differences between the two conductors of each capacitor is then: ∆V1 = Q C1 ∆V2 = Q C2 and ∆V3 = Q C3 [11] By adding ∆V1, ∆V2 and ∆V3, we get the total potential difference between A and B or: CAPACITANCE-5 August 7, 2007 Q Q Q ∆V = V A − VB = + + C1 C 2 C3 [12] and by definition, this implies that the equivalent capacitance between A and B is: V − VB 1 1 1 1 = A = + + Ceq Q C1 C 2 C3 [13] In general, for n capacitors in series: 1 = Ceq n ∑C 1 i =1 [14] i Capacitors in parallel Figure 4 shows a set of capacitors in a parallel configuration. The left hand plate of each capacitor is connected to the positive terminal of a battery, and are therefore all at the same electric potential. The right hand plates are all connected to the negative terminal, and are also all at the same potential. Therefore, the potential difference across each capacitor is the same when connected in parallel. C1 A B C2 C3 + – ∆V Figure 4: capacitors arranged in a parallel configuration. As with the discussion of capacitors in series, when these devices are connected to the terminals of the battery, charge begins to flow. The net result is that the left hand plates become positively charged, while the right hand plates become negatively charged. The flow of charge ends when the potential difference across each capacitor is exactly the amount across the terminals of the battery, ∆V. Rearranging equation [4], this implies that the maximum charge of each capacitor, achieved when the potential difference is ∆V, is given by: Q1 = C1 ⋅ ∆V Q2 = C 2 ⋅ ∆V and CAPACITANCE-6 Q3 = C3 ⋅ ∆V [15] August 7, 2007 The total charge transferred in reaching this steady state is: Q = Q1 + Q2 + Q3 [16] due to conservation of charge. Therefore, recognizing again that ∆V = VA – VB, the equivalent capacitance between A and B is: Ceq = C ⋅ ∆V + C 2 ⋅ ∆V + C3 ⋅ ∆V Q = C1 + C 2 + C3 = 1 V A − VB ∆V [17] In general, for n capacitors in parallel: n Ceq = ∑C i [18] i =1 Note: Capacitor value codes (in pF): 3rd digit Multiplier 0 1 1 10 2 100 3 1000 4 10,000 5 100,000 6, 7 not used 8 0.01 9 0.1 Letter D F G H J K M P Z Tolerance 0.5 pF 1% 2% 3% 5% 10% 20% +100, -0% +80, -20% Example: If a capacitor is marked 105, this means 10 * 100,000 = 1 × 106 pF = 1000 nF = 1 µF. The letter added to the value is the tolerance as indicated in the table above. EXPERIMENT NOTE: after each measurement of capacitance, turn the meter off before disconnecting the device you have measured. Part 1: measuring commercial capacitors 1-1. Connect the 1st commercial capacitor to the multimeter, and turn the dial to the capacitance setting: CAPACITANCE-7 August 7, 2007 Record the capacitance measured, as well as the uncertainty. 1-2. 1-3. 1-4. 1-5. 1-6. Repeat 1-1 with the 2nd and 3rd capacitors. With the leads disconnected from any commercial capacitor, measure the inherent capacitance of the meter. Record this value and its uncertainty in your notebook. This capacitance is in parallel with the commercial capacitors when measured, so correct your measured values accordingly. Connect the three capacitors in series, and record the overall capacitance including uncertainty. Remember to correct for the meter’s capacitance. Connect the three capacitors in parallel, and record the overall capacitance including uncertainty. Remember to correct for the meter’s capacitance. Based on the corrected values of the individual capacitances measured previously, calculate the expected values for combining the devices in series and in parallel, including uncertainties. Record these calculations in your notebook. You should have a table that looks something like: Configuratio n C1 C2 Measured capacitance (corrected) Uncertainty Calculated capacitance C3 Uncertaint y C1, C2, C3 in series C1, C2, C3 in parallel Part 2: Investigating the relationship between capacitance and plate spacing Now you will use the meter to determine the capacitance of the parallel plate capacitor for a number of different plate separations ranging from d ≈ 0.5mm to d ≈ 6.0mm. Make sure that the paper spacers do not cover the metal plate, otherwise there will be an error in the capacitance measured value. 2-1. Starting with two spacers, measure the total spacer thickness, d, with the caliper or the micrometer. Record this value in a table in your lab book, along with the associated uncertainty. 2-2. Position a pair of spacers on either side on the bottom plate. Make sure that the spacers do not overlap onto the plate itself. Place the top plate face down on top, CAPACITANCE-8 August 7, 2007 taking care to ensure that the plates are aligned. 2-3. Weight the top plate after placing the spacers. 2-4. Record the capacitance and the associated uncertainty in your notebook. 2-5. Add one additional spacer on each side of the lower plate, and repeat steps 2-1 through 2-4. Continue this procedure until you have measured capacitance with all spacers available. Plot the results as a linear graph, 1/d vs. C, plotting 1/d on the y axis as it has the larger uncertainties. From this graph, determine εo. Compare this value with the tabulated εo. (Note: the area of the plates is 0.0103 m2 ± 0.7%.) Part 3: Investigating the effect of using a dielectric material Again, use the meter to investigate the capacitance with various dielectrics inserted. The procedure is similar to that in part 2, except that for simplicity you will only collect capacitance values at two plate separations for each material. 3-1. Measure the thickness of one piece of a given dielectric. Record this value and its uncertainty in your lab book. (NOTE: for testing Bristol board, use a minimum of 3 sheets for your first plate separation measurement.) 3-2. Place the dielectric on the lower plate, and position the upper plate on top, taking care to ensure that the plates are aligned. The dielectric should cover the entire lower plate. Weight the top plate down. 3-3. Measure the capacitance of this configuration, recording the value and its uncertainty in your lab book. NOTE: if the capacitance meter reading does not stabilize fairly quickly, disassemble the capacitor and try again. 3-4. Now measure the thickness of two pieces of this dielectric. Repeat the capacitance measurement with two pieces, and record the necessary data. (For Bristol board, your second plate separation measurement should involve more than 3 sheets.) 3-5. Repeat steps 3-1 to 3-4 for the remaining dielectrics. For each material, use the two thickness measurements to determine the dielectric constant by comparison with the data collected previously with the air capacitor. Thus determine the dielectric constant of each material, including the uncertainty. CAPACITANCE-9 August 7, 2007 Informal lab report expectations for the Capacitance lab Maximum length for report = 5 pages on 8.5”x11” paper, stapled together, min. 12 pt font size. Follow the organizational structure below. Part 1 Measuring commercial capacitors • • give a table of measured and calculated capacitances, with their uncertainties, for both individual capacitors and series and parallel network of capacitors; a skeleton of such a table is shown in the lab write-up to show how it could be organized show calculations of the net capacitance in series and parallel, and the associated uncertainties. Part 2 Investigating the relationship between capacitance and plate spacing • • • give a table of corrected measured capacitances together with the associated plate spacing: give the uncertainties here as well. provide a plot of inverse plate spacing versus the capacitance data, together with a linear fit of the data: ensure the plot has a title, proper axis labels with units, and that the linear fit slope and intercept are quoted on the graph, together with their uncertainties o the linear fit must be calculated using weighted linear regression, whether it is done by hand in a spreadsheet, or by a software program (note that Excel does not perform weighted linear regression in its straight line fits) o if the linear fit is done by hand, show the spreadsheet calculations o if the linear fit is done by a software package, state what the package is, and what parameters were used, if any show the calculation of εo and its uncertainty from the slope of the fit and its uncertainty; compare to the accepted value. Part 3 Investigating the effect of using a dielectric material • • • • give a table of corrected measured capacitances and their corresponding plate separations, with uncertainties, for each dielectric material give a mathematical derivation relating the dielectric constant of a given dielectric material to that of air using the capacitance equations for parallel plate capacitors, one with air, the other with a dielectric material; use this derivation to calculate the dielectric constant for each of the materials tested give a sample calculation of the dielectric constant for one of the dielectric materials give a table summarizing the dielectric constants of the materials, together with their uncertainties; compare to accepted values Part 4 Conclusions • • • • summarize results: how well do measured and calculated capacitances agree in part 1? How close is your estimate of εo to the accepted value in part 2? Are the dielectric constants you calculated in part 3 reasonable? Discuss systematic errors. CAPACITANCE-10