Future Character of Conflict

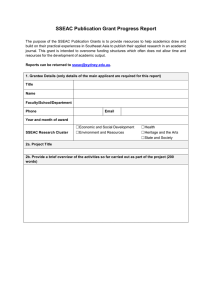

advertisement