X-ray Powder Diffraction II Peak Intensities

advertisement

X-ray Powder Diffraction II

Peak Intensities

Chemistry 754

Solid State Chemistry

Lecture #10

Outline

• Elastic scattering of X-rays by atoms

• Diffraction peak intensities

–

–

–

–

Structure Factors

Multiplicity

Lorentz and Polarization Factors

Temperature Factors

• Neutron diffraction

• Electron diffraction

1

Interaction of X-rays with Matter

These are the

diffracted X-rays

Elastic Scattering by an Electron

• Charged particles (electron) scatter

electromagnetic radiation (x-rays)

– The varying electric field of the X-ray induces an oscillation

of the electron

– The oscillating electron then acts as a source of

electromagnetic radiation

– In this way the x-rays are scattered in all directions

• JJ Thompson analyzed the scattering and found

that:

I = I0[(μ0/4p)2(e4/m2r2)sin2α]

I = I0(K/r2) sin2α

α is the angle between the scattering direction and the

direction in which the electron is accelerated

r is the distance from the scattering electron

K is a constant

2

Scattering by an Atom

We can consider an atom to be a collection of

electrons. The electrons around an atom scatter

radiation in the manner described by Thompson.

However, due to the coherence of the radiation we

need to consider interference effects from different

electrons within an atom. This leads to a strong

anglular dependence of the scattering. We express

the scattering power of an atom by its form factor (f).

X-ray Form Factors

25

The form factor is

equivalent to the atomic

number at θ = 0

Form Factor, f

20

Ca

Ca2+

15

10

The form factor

drops rapidly as a

function of (sin θ)/λ

5

0

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

Sin(θ)/λ

3

The Effect of Form Factors on

Diffraction Patterns

4500

TbBaFe2O5 - 70 K

Neutron Data

TbBaFe2O5 - 300 K

Synchrotron X-ray

4000

Intensity (Arb. Units)

3500

Intensity

3000

2500

2000

1500

1000

500

0

5

25

45

65

2-Theta (Degrees)

The peak intensities drop off at

high angles in an X-ray diffraction

pattern because the form factor

decreases

10

30

50

70

90

110

130

2-Theta (Degrees)

Neutrons are scattered from the

nucleus and the form factor is not

angle dependent. Intensities do

not drop off at high angle.

Diffraction Intensities

The integrated intensity (peak area) of each powder

diffraction peak is given by the following expression:

I(hkl) = |S(hkl)|2 × Mhkl × LP(θ) × TF(θ)

–

–

–

–

S(hkl) = Structure Factor

Mhkl = Multiplicity

LP(θ) = Lorentz & Polarization Factors

TF(θ) = Temperature factor (more correctly

referred to as the displacement parameter)

This does not include effects that can sometimes by

problematic such as absorption, preferred orientation

and extinction.

4

Structure Factor

The structure factor reflects the interference between atoms in

the basis (within the unit cell). All of the information regarding

where the atoms are located in the unit cell is contained in the

structure factor. The structure factor is given by the following

summation over all atoms (from 1 to j) in the unit cell:

S(hkl) = Σj fj exp {-i2π(hxj+kyj+lzj)}

– fj = form factor for the jth atom

– h, k & l = Miller indices of the hkl reflection

– xj, yj & zj = The fractional coordinates of the jth atom

To evaluate the value of the imaginary term in the exponential

function, remember Euler’s equation:

exp (-ix) = cos(x) – i sin(x)

The value of this function is a real number when x is a multiple of

2π. It is equal to 1 for even multiples of 2π and -1 for odd

multiples of 2π.

Structure Factors: Example CsCl

• Let’s calculate the structure factors for the first 6

peaks CsCl. To do this we need to know the atomic

positions and the Miller Indices.

Cl at (0,0,0)

Cs at (½,½,½)

5

Structure Factors: Example CsCl

S(hkl) = Σj fj exp {-i2π(hxj+kyj+lzj)}

S(hkl) = fCl exp {-i2π([h×0]+[k×0]+[l×0]}

+ fCs exp {-i2π([h×½]+[k×½]+[l×½]}

S(hkl) = fCl exp {0} + fCs exp {-iπ(h+k+l)}

S(hkl) = fCl – fCs when h+k+l is an odd number

S(hkl) = fCl + fCs when h+k+l is an even number

S(100) = fCl - fCs

S(111) = fCl - fCs

S(210) = fCl - fCs

S(110) = fCl + fCs

S(200) = fCl + fCs

S(211) = fCl + fCs

Systematic Absences: Body Centering

Recall that earlier we said that for a body centered space

group all of the peaks where h+k+l is an odd number will

be missing. Consider the structure factors for sodium

which has the BCC structure with Na atoms at (0,0,0) and

(½,½,½). The equations will be just like CsCl, but the two

form factors will be equal.

S(hkl) = fNa exp {-i2π([h×0]+[k×0]+[l×0]}

+ fNa exp {-i2π([h×½]+[k×½]+[l×½]}

S(hkl) = fNa exp {0} + fNa exp {-iπ(h+k+l)}

S(hkl) = fNa – fNa = 0 when h+k+l is an odd number

S(hkl) = fNa + fNa = 2fNa when h+k+l is an even number

6

Int.

Na (BCC)

(110)

12000

10000

4000

(220)

(200)

6000

(211)

8000

2000

Simulated X-ray

powder

diffraction

patterns

[Calculated with

Diamond]

0

20

30

40

2Theta

50

60

Int.

(210)

(220)

(110)

20000

(200)

30000

(111)

40000

(100)

50000

(211)

CsCl

60000

10000

0

20

30

40

2Theta

50

60

Multiplicity Factor

In a powder diffraction experiment the d-spacings for related

reflections are often equivalent. Consider the examples below:

Cubic

– (100), (010), (001), (-100), (0-10), (00-1) → Equivalent

Multiplicity Factor = 6

– (110), (-110), (1-10), (-1-10), (101), (-101), (10-1),

(-10-1), (011), (0-11), (01-1), (0-1-1) → Equivalent

Multiplicity Factor = 12

In general for a cubic system where the Miller indices are n1, n2 and

n3 (all unequal) the multiplicity factors Mhkl are:

n100 (i.e. 100) → M = 6

n1n10 (i.e. 110) → M = 12

n1n1n2 (i.e. 221) → M = 24

n1n1n1 (ie 111) → M = 8

n1n20 (ie 210) → M = 24

n1n2n3 (ie 321) → M = 48

The multiplicities are lower in lower symmetry systems. For example

in a tetragonal crystal the (100) is equivalent with the (010), (-100)

and (0-10), but not with the (001) and the (00-1).

7

Lorentz Factor

There are a number of factors that lead to a theta

dependence of the peak intensities (integrated

intensities).

• Diffraction can occur for angles slightly different from the value

predicted by Bragg’s Law → I α 1/sin(2θ)

• The number of crystals oriented in such a way as to satisfy Bragg’s

Law is highest for low angles → I α cos(θ)

• The fraction of the diffraction cone that intersects the detector is

highest at low angles → I α 1/sin(2θ)

When combine these considerations and do some

trigonometric manipulation we get the Lorentz Factor:

I α 1/(4sin2θ cosθ)

Polarization and the LP Factor

An X-ray propagating in the x-direction will have an

electric vector oriented in the yz plane. The y and z

components of the X-ray will be scattered differently

because the angle between the scattered beam and the

electric field gradient will differ, as derived by

Thompson. This leads to the polarization factor:

I α (1+cos22θ)/2

Typically the Lorentz and Polarization terms are combined

to give the Lorentz-Polarization (LP) factor.

I α (1+cos22θ)/(8sin2θ cosθ)

8

Temperature Factor

The vibrations of atoms in a crystal lead to an angle dependent effect

on the diffracted peak intensities. The more an atom vibrates the

scattering power is decreased, because the scattering power of the

atom is smeared out. As an approximation we can assume that all atoms

vibrate equally. In that case the TF can be expressed by the equation:

TF(θ) = exp {B(sin θ/λ)2}

Where the coefficient B is the isotropic temperature factor.

– B is proportional to the mean squared displacement of the atoms

– Typical values for inorganic extended solids range from 0.5 to 1.5.

– The temperature factor has its biggest impact at high angles.

More sophisticated treatments assume

– Different values of B for each crystallographically independent atom

– Anisotropic vibrations (elliptical in shape rather than spherical).

5

1.2

Lorentz-Polarization

4

3.5

1

0.8

3

2.5

0.6

2

0.4

1.5

1

Temperature Factor

LP

LP Inc. Beam Mono

Temp. Factor (B=1)

Temp. Factor (B=2)

4.5

0.2

0.5

0

0

50

100

2-Theta

150

0

200

9

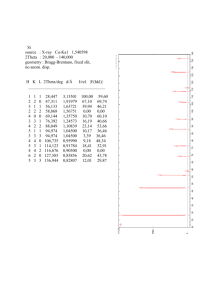

Int.

(220)

(210)

20000

(200)

30000

(111)

40000

(211)

CsCl

(110)

50000

(100)

Intensity

Calculations

for CsCl

60000

10000

0

20

h

k

l

0

0

1

0

0

1

0

0

1

1

0

1

1

2

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2Theta [°] d-spacing [Å]

21.54

30.64

37.76

43.88

49.39

54.47

63.80

4.123

2.915

2.380

2.062

1.844

1.683

1.458

30

40

2Theta

S

LP

34.66

58.72

31.54

51.98

29.32

47.68

44.64

6.80

3.23

2.05

1.47

1.12

0.90

0.63

50

60

Mult. Relative Int.

6

12

8

6

24

24

12

37

100

12

18

17

37

11

Neutron Diffraction

Diffraction from crystals can also be carried out with neutron and

electrons. The basic concept are the same though there are

important distinctions. Let’s begin with the DeBroglie relationship.

λ = h/p = h/mv

but the kinetic energy, E, and velocity, v, of a particle are related by

the expression

E = (1/2)mv2 → v = sqrt(2E/m)

combining the two relationships gives

λ = h/sqrt(2mE)

finally for thermal neutrons from a reactor source the energy of an

electron is E = kT so that

λ = h/sqrt(2kT)

Typical values for a neutron reactor source are 300<T<400K and 1.0

A< λ < 2.5 A.

10

Reactor Diffractometers

Thermal Neutron Instruments at NIST

BT1 Powder Diffractometer

BT1 Powder Diffractometer at NIST

11

X-rays vs. Neutrons

• Neutron beams are highly penetrating (penetration depths of

centimeters-decimeters), whereas X-rays are highly attenuated

by matter (penetration depths of microns-millimeters).

– Larger samples are needed for neutron diffraction

• Neutrons are scattered from nuclei, whereas X-rays are

scattered by electrons

– Neutron scattering factors do not drop off with increasing θ

• Neutron scattering power varies irregularly with atomic number

and mass number, whereas X-ray scattering power varies

smoothly with atomic number.

– Neutrons are more sensitive to light elements (H, N, O, F, C, etc.)

and isotope distributions

– Some elements strongly absorb neutrons and cannot be easily

studied (B, Cd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Dy, Hf, Ir, Hg), some are essentially

transparent to neutrons (V) or have negative scattering lengths (Ti,

Mn)

• Neutrons have an intrinsic magnetic moment, whereas X-rays

have no magnetic moment

– Neutrons are used to determine ordered magnetic structures

Electron Diffraction

Diffraction from crystals can also be carried out with neutron and

electrons. The basic concept are the same though there are

important distinctions. Let’s begin with the DeBroglie relationship.

λ = h/p = h/mv

but the kinetic energy, E, and velocity, v, of a particle are related by

the expression

E = (1/2)mv2 → v = sqrt(2E/m)

combining the two relationships gives

λ = h/sqrt(2mE)

The energy of an electron is related to the accelerating voltage, V,

by the relationship E = eV. Upon correcting for relativistic effects

we get an approximate relationship between the wavelength (in

Angstroms) and the voltage

λ = sqrt(150/V)

Typical values for a electron microscope are V ~ 100 kV and λ ~ 0.04

Angstroms

12

Transmission Electron Microscope

This is the CM300 UltraTwin Field Emission Gun

TEM.

It is located in the Campus

Center for Electron Optics

(CEOF) in the MSE

department

X-rays vs. Electrons

• Electrons are highly attenuated by matter (penetration depth of

nanometers), whereas X-rays are strongly attenuated by matter

(penetration depths of microns-millimeters).

– Data collection done under high vacuum

– Data collection is usually a transmission measurement (TEM) on a thin

sample or crystal

• Electrons beams can be highly focused, whereas X-rays are

difficult to focus

– The electron beam is usually focused onto a very small micro-single

crystal

• Electron scattering power drops off strongly as a function of 2theta, whereas X-ray scattering power drops off smoothly as a

function of 2-theta

– Data sets are often collected over a very limited angular range

(± 4° 2-theta)

• Diffracted electrons can interact strongly with the lattice making

it difficult to get reliable intensities, whereas X-ray intensities and

peak positions can be determined with a great deal of accuracy

– Structure refinement and solution is challenging

13