Hydroelectric Power Plants as a Source of Renewable Energy

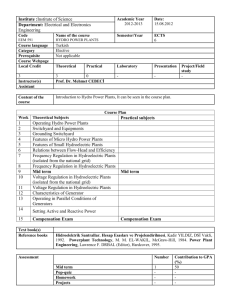

advertisement