DRAFT DO NOT CITE OR DISTRIBUTE WITHOUT AUTHORS

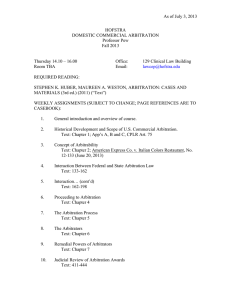

advertisement