DRAFT DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE WITHOUT AUTHORS

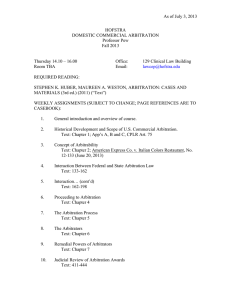

advertisement