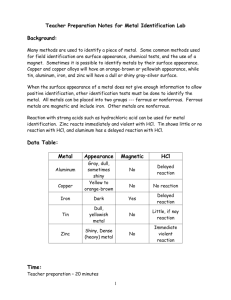

NONFERROUS METALS - National Bureau of Economic Research

advertisement