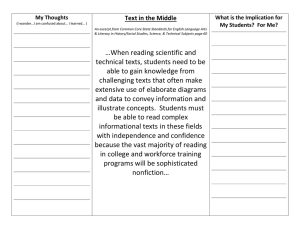

Reading and Writing Standards - NZ Curriculum Online

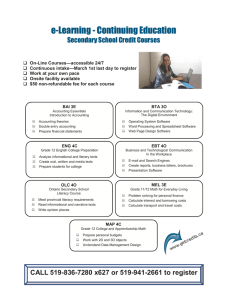

advertisement