A Study of Critical Thinking Skills in the International Baccalaureate

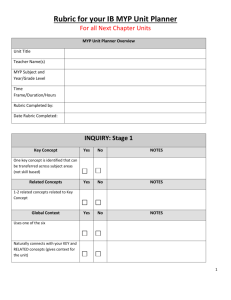

advertisement