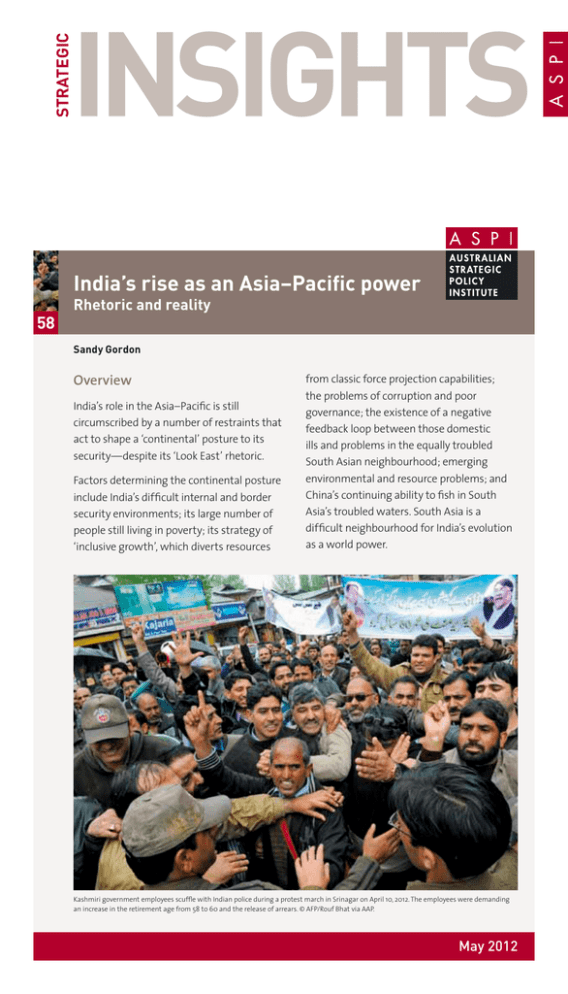

india`s rise as an asia–Pacific power

advertisement