Factors that determine nominal exchange rates and empirical

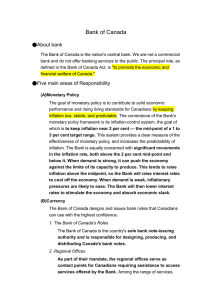

advertisement