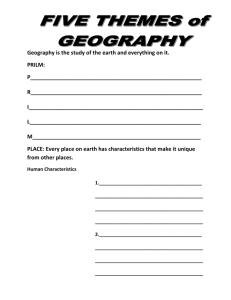

AP Human Geography Course Description

advertisement