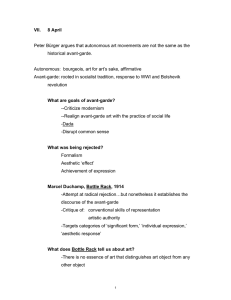

“High Modernism”: The Avant-Garde in the Early 20th Century

advertisement