Pedagogical framework and didactic guidelines

advertisement

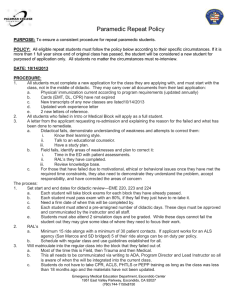

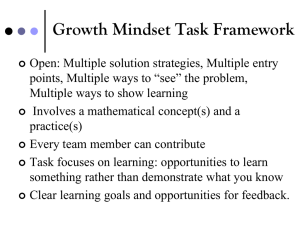

Pedagogical framework and didactic guidelines (June 2004) Helene (Minerva) Project 2 University of Lincoln HELENE Lead Institution Brayford Pool, Lincoln, LN6 7TS, United Kingdom Coordinating Project Director: Dr. Terence Karran tkarran@lincoln.ac.uk Project Manager: Dave al Bahrani-Peacock dpeacock@lincoln.ac.uk Oulun Yliopisto PL 4600, 90014 Oulun Yliopisto, Finland Project Manager: Sauli Pajari sauli.pajari@oulu.fi Universitat Pompeu Fabra Edifici Jaume I, Ramon Trias Fargas 25-27, E-08005 Barcelona, Spain Project Manager: Professor Francesc Pedró francesc.pedro@upf.edu Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Ammerländer Heerstraße 114-118, D-26111 Oldenburg, Germany Project Manager: Prof. Dr. Uwe Schneidewind Uwe.Schneidewind@uni-oldenburg.de The HELENE Project is granted by the EU Commission Grant period: 2002 - 2004 3 Index 1. PEDAGOGICAL FRAMEWORK............................................4 1.1. WHAT IS LEARNING? .......................................................5 1.2. HOW TO FACILITATE LEARNING ..........................................7 1.2.1. Activating previous knowledge................................... 7 1.2.2. Providing a real context in order to exercise competencies ................................................................... 7 1.2.3. Organising content around its application.................... 8 1.2.4. Favouring the transfer to other contexts and situations. 8 1.2.5. Putting learning to the test........................................ 9 1.2.6. Creating opportunities for collaborative learning .......... 9 1.3. HOW TO MOTIVATE LEARNING BASED ON SIGNIFICANCE ........11 2. DIDACTIC METHODOLOGY .............................................13 2.1. ALTERNATIVE MODELS OF E–LEARNING ..............................14 2.2. OUR METHODOLOGICAL MODEL ........................................17 3. THE ROLE OF THE TEACHING STAFF AT THE DIFFERENT STAGES OF THE PROGRAMME ............................................19 3.1. PREPARATION OF THE MODULE AND MATERIALS ...................20 Didactic guidelines ....................................................... 20 3.2. DEVELOPMENT OF THE COURSE.........................................23 Didactic guidelines ....................................................... 23 3.3. ASSESSMENT ...............................................................26 Didactic guidelines ....................................................... 26 4 1. Pedagogical framework For a variety of reasons, the process of teaching and learning for working professionals has never been a priority concern for specialists in psycho-pedagogy or didactics. In practical terms it is as if it were assumed that whatever a teacher decides to do and, how in the end they do it, on the basis of their notes and manuals, is the most suitable. Underpinning this view is the further assumption that nobody knows the subject matter better than the teacher. Though often true, this approach only guarantees that the teacher is familiar with the subject, not that they now how to deliver it in a manner that enables the student to learn. This state of affairs is yet more evident in the diversity of e-learning materials. In order to achieve a successful learning experience, e-learning courses must be based on a solid theoretical framework allowing teaching staff the resources to provide both individual student attention and for the creation of didactic units, which are then properly situated within the students’ learning processes. In this context, the purpose of this Pedagogical Handbook is to provide all participating teachers in Project Helene a common basis for the design of the study materials. All participating institutions whose project managers contributed to this shared vision of e learning have agreed upon the handbook. 5 1.1. What is learning? Learning is... Learning is a process through which people modify their structure of knowledge and abilities concerning a specific theme, broadening or changing it, which can even extend to their attitudes and behaviour. In short, when we learn or acquire new knowledge our existing knowledge is usually modified. This process may also entail a review or restructuring of our existing knowledge to allow for the new. That is to say, what we knew before may have to be changed, either wholly or in part, and, therefore, we will have to find a new equilibrium accommodate what we now know. Of course there are different styles of learning. But reference to styles should not be interpreted as an essential difference in the way in which learning is configured. It is more helpful to see styles of learning as the strategies an individual develops when facing a learning activity, that is to say, the way in which he or she resolves the demands and problems that arise in the learning process. There are three basic problems we face when learning: • problems of understanding: what we have to learn is either poorly taught or simply pre-supposes some previous knowledge which we do not possess. We often say that what is explained to us is not readily understood. • problems of integration: what we have learned does is not easily integrated with what we already knew or thought we new. The problems that appear in this case require a solution. A temporary conflict arises between what was known and what is aimed at being taught, which the learner must solve by either rejecting what they previously knew or questioning what is supposed to be learnt now. • problems of significance: what we have to learn has no meaning, makes no sense, or is, seemingly, of no use for us. That is to say, it is not meaningful to us and if knowledge is not meaningful it will not be assimilated. In essence, a process of temporary, isolated memorisation takes place in order to respond to a requirement at one given moment as might, for example, happen when preparing for an exam. Once this situation has been hurdled, what has theoretically been learnt becomes disregarded and completely forgotten about. a process through which people modify their structure of knowledge and abilities concerning a specific theme, broadening or changing it and even their attitudes and behaviour. 6 Often, though not always, when content has to do with human phenomena - individual or social, or with elements that are closely related to the quality of life, such as health, or with our way of seeing the world, learning may also imply contradictions and changes to attitudes, values and behavioural rules. In these types of situations, new knowledge or learning may be deeply resented and/or resisted by individual or whole communities of learners. This too can often lead to knowledge being disregarded or ignored. For example, some communal attitudes to race or gender, or even the perceived need for education itself, may take a very long time to respond to changes in knowledge about, and thus, understandings of, human society. 7 1.2. How to facilitate learning Psycho-pedagogical research provides us with several basic – and contrasted - principles concerning how to facilitate and optimise adult learning that contrast with traditional teaching practice. They are as follows: Basic teaching principles 1. Activating prior knowledge. 2. Providing a real context. 3. Organising content around its application. 4. Favouring the transfer to other contexts and situations. 5. Putting learning to the test. 6. Creating opportunities for collaborative learning. Let us look at each one separately. 1.2.1. Activating previous knowledge All professionals possess a set of prior knowledge pertaining to a module’s subject matter. Without such knowledge they would be incapable of making sense of any content since they would lack the necessary references required enabling comprehension and integration. It has been shown that learning efficacy is greater when the first activity suggested by the teacher or the units is aimed, precisely, at the activation of such previous knowledge. Achieving it is easy: suffice to introduce questions or exercises that, either directly or indirectly, force participants to activate what they already know. 1.2.2. Providing a real context in order to exercise competencies It also seems clear that the development of competencies is achieved, precisely, by putting them into motion: taking decisions and examining the consequences instead of limiting oneself to memorising the theoretical bases. This is why it is highly recommended to utilise a procedure of active learning, situating participants within a context 8 that forces individuals to put the required competencies into motion, and either acquire or develop them. In order to achieve this, it is most recommended that one should generate a practical case, or, at least, start the process by situating participants in as close a context as possible to the real professional world. Despite no being a complete case, the situation should be taken up every time an attempt is made to get participants to take decisions or to recapitulate. 1.2.3. Organising content around its application It is common, in any course, for the teacher to decide to follow the sequence suggested by disciplinary or deductive logic – from general points to specific ones. When dealing with the training of professionals, a clear distinction should be made between what is reference material (an article or a part of a didactic unit, for example) and what is teaching material or an intervention of a didactic nature. In this case, the logic that should be followed is that which suggests, at all times, the practical case or the starting situation. Therefore, didactic material – which should be distinguished from reference material – should be presented following the logic called for given the situation or the case presented for its appropriate solution. 1.2.4. Favouring the transfer to other contexts and situations Given that course orientation is towards the development of competencies, it is essential to document as many times as possible how an expert would solve situations in which he may have to put the competencies in question into play, in as broad a variety of contexts as possible. In this way, the transfer of competencies and content will be projected towards other situations and problems. 9 The best way to do so consists of offering as many solved situations and practical mini-cases as possible, showing how an expert solved them, whether well or poorly, and why. These resources should always allow the student to identify the different contexts and the peculiarities with regard to the reference situation. 1.2.5. Putting learning to the test Any activity that is suggested to the student, once done, should give rise to as immediate feedback as possible, so that the student will not be in suspense as to whether or not he has learnt properly. When dealing with an e–learning course, immediacy should preside both with regard to both the teacher’s intervention and, above all, the presentation of the material. • It is most recommendable for self-assessment exercises to be included incorporating automatic answers indicating the type of mistake made and where to go to obtain the knowledge to amend them. • When correction and assessment is deferred in time (for example, because it is a long test or written assignment), the student should receive an immediate acknowledgement of receipt and estimation as to when he or she will receive the results. 1.2.6. Creating opportunities for collaborative learning Another characteristic of e–learning courses is the participant’s feeling of isolation. Not just because of this, but also because modern psychological theories such as constructivism has proved that learning is most readily consolidated when it takes place, or is evaluated, within a social context – i.e., in a group, it is most important to allow for critical exchanges among participants and, if possible, the joint solution of a problem or situation. 10 In short, the use of participant group communication should be optimised, not just through debate and discussion but, whenever possible, by creating opportunities for co-operative – and sometimes competitive – group work. 11 1.3. How to motivate learning based on significance Adults – involved as they are in the development of their own personal, family and professional projects - require clear, and constant motivation so that a learning process can grab and keep their interest and attention. This is especially important if the routine of continuous class attendance does not exist. In professional or work-oriented training, the best way to maintain motivation and enthusiasm is to guarantee that learning will have a special significance for them. In short, it is vital that the content provided will be professionally meaningful and linked to relevant situations or problems they might encounter. However, beyond this, even when presenting content it is important to always bear in mind the need for the teacher – or the didactic material – to encourage and sustain motivation. To do so it must be guaranteed that whatever is presented or shown shall: • have an immediate, practical application. That is to say, when the importance of what is being learned is delivered with due regard to the applications that interest the students. For example, in the context of their working environment or their everyday lives; or • solve a concrete cognitive problem. That is to say, when it appears that this learning will help the students to fill a void in their knowledge or to put an end to an inexcusable limitation. For example, using a word processor, database or spreadsheet; or • question dominant viewpoints or opinions held by the majority. That is, when the surprise factor is used to advantage overturning by means the of a cognitive presupposed challenge knowledge on strategy, which the participants base their decisions; or • be based on a reference to the immediate current situation. Especially if dealing with the professional world itself. That is to say, when the adult learner clearly sees the link When can learning be meaningful for the adult, professional student? 12 that exists between the events and facts, that interest him personally and professionally, and what he has to learn. For example, when learning is based on a news item that appears in a professional journal. 13 2. Didactic methodology Obviously, such considerations, as discussed above, contrast with the image given by traditional teaching, including professional training courses, where emphasis is always placed upon content and is not sufficiently sensisitive to the student. In fact, an alternative approach comes to mind, at almost the opposite extreme, far more student-focused and, thus, far more open, which is just what an elearning system requires. 14 2.1. Alternative models of e–learning In continental Europe, traditional university teaching consists fundamentally of lectures. From the methodological point of view, many university classes still greatly resemble, formally speaking, the lessons given at medieval universities. The same can be said of many e–learning programmes. In both cases, the problem is not that all hinges on the teacher, but rather that for reasons which are often beyond the teacher’s wishes, poor use is made of the oral lessons or of the didactic units that are designed to replace them. In traditional teaching requiring student presence, the teacher becomes a means of transmission, merely, of oral content, which is complemented by resorting to other written means, such as manuals for example. In traditionally structured e–learning programmes this point of view is also shared, and this is reflected in didactic units that are solely conceived as a manual for presentation. As a matter of fact, such units that have generally been provided for e-learning have been solely conceived of as electric/virtual versions of the traditional handbooks, notes, lectures, and all the other paraphernalia of the rapidly passing, if not actually past, "printed word" dominated learning culture. In both cases, pedagogic emphasis is placed on the devlivery of How do they differ? content. The teaching staff focuses on compiling and generating – via research - the content they will sooner or later disseminate and, at the end of a course, assess. Under a traditional pedagogic regime therefore, a learning session becomes, at best, a unidirectional act of communication, which, if it goes well, might engender some doubts or comments from the more confident students. In an e–learning programme, to replicate this model is an act of gross negligence, betraying a lack of pedagogical engagement with either the technology or the craft of teaching, on behalf of the tutor. An alternative model does exist that encourages the teacher to become a guide, mentor, and facilitator of learning. In this model the focus is shifted from the tutor who merely broadcasts information and the didactic units that simply present themes, to the student as an active learner and the activities that students should accomplish, alone or accompanied by others. Under this model: 1. The aims and objectives for the student to fulfil are very clearly specified, as are the contents or the abilities they will be expected to command, specifying the competencies to be achieved and how these will be assessed. There is a commonly held belief that this is the function that all traditional Basic characteristics of the teaching and learning model 15 educational programmes meet, when in reality they are frequently, just indices of content covered by the student taking the course, providing no evidence, for example, of the degree of command or competence attained by the student. 2. A learning framework is designed advising the student about the activities that he or she should develop in order to achieve the specified aims and objectives of the course or module. In continental Europe, the activity par excellence has always consisted of attending class and listening to lectures or reading a manual. What has to be achieved in an e-learning system is for the student to play an active role in attaining the aims and objectives, that is to say, that he or she achieves the required learning outcomes by means of performing a variety of activities: by searching and finding, by comparing and contrasting, and by doing and debating. 3. The process is put into practice with the teacher acting as a supervisor and facilitator and, at the same time, as a source of activities and information. In the teacher, the student must find the reference point which, when faced with a doubt, may offer some guidance. The teacher is also a privileged source of knowledge to which one should resort when appropriate. 4. The result is assessed. It should not be expected that everyone is equally interested in all of the modules, or is equally dedicated. If the aims have been well designed, this process will be relatively simple. What cannot be done is to mix the assessment of elements that are not connected to the learning process such as, for example, creativity, criticism or personal effort. These three aspects are, in themselves, most important values, but the mission of assessment is to measure, which aims among those proposed have been achieved by each student, and to what extent. This is why it is so important for the definition of aims to be clear, concise, unmistakable and, above all, well understood by the student. 5. The process is assessed. The results of student assessment are already an initial indication of whether all of the elements of the process have been correctly designed, whether correspondence exists between the aims and objectives set, and the activities that are proposed with the assessment mechanisms used. 16 17 2.2. Our methodological model The course of study will be provided on an open basis via Internet. The didactic methodology utilised throughout the course will be based on case studies, participant discussion fora, and group-work. Participants shall engage in both individual and group practical work, and all significant points on the curriculum will include gateway tests, tests that only allow progression once they have been satisfactorily accomplished, based on multiple-choice self-assessment questions. Each module comprises: The didactic sequence of each module 1. An introduction or synthesis detailing the aims, elements of the module, assessment, timing and recommended itinerary. 2. A central unpublished text that the participant may print (around 8000/10000 words). Is there not a danger of reinventing the book here. What purpose does so much text serve on a medium that renders text so unfriendly? Doesn’t this contradict all that was said above regarding traditional delivery methods? 3. A set of self-correctable, self-assessment tests. 4. A final assessment test that the participant submits to the teacher at the end of each unit. 5. A final exercise to be sent to the teacher, which shall generally consist of a short 6-8-page essay. 6. A discussion forum. 7. Frequently asked questions 8. Personalised access to the module tutor via e-mail. 9. Annexes and learning complements: bibliography, related articles and a variety of links. At the end of the module, each participant will be given a CD containing the introduction, the unpublished central text, the assessment tests and the exercises pertaining to each unit that makes up a module. This material, including updates and revisions, will be therefore, be available throughout the period of study and on the course e-learning zone located at http://cjs072.upf.es/helene, the course’s own e-learning platform which is based on the open source Moodle platform (http://moodle.org) The following elements are to be found on the website: Utility of the course website 18 • All course documentation will be available throughout the course in web format and on CD-ROM at the end of the course, as well as in the form of web pages that may be consulted via Internet. • Furthermore, students shall have the downloading the contents of the teaching possibility of units to their computers, so that they will be able to do most study activities off–line. • Communication between teachers and participants will take place on the basis of discussion fora. 19 3. The role of the teaching staff at the different stages of the programme It is easy to see how, in an e–learning programme, the teaching staff takes on a multitude of functions, which generally coincide, with the different stages of the course. Three stages of such orientation are most notable: Stages of development of the programme 1. Preparation of the module and materials 2. Development of the course 3. Assessment 20 3.1. Preparation of the module and materials The task of designing the didactic process of a module and, therefore, all activities of the whole course of study, which the students are to carry out, comes down to the teaching staff. But, what is involved in designing the didactic process? What is involved in designing the didactic process? Didactic guidelines 1. Defining the learning aims and objectives that the student must achieve to successfully complete a module. These aims and objectives must be expressed in terms of competencies that the participant will be able to demonstrate upon completion of the module, and must be, in so far as possible, measurable, so that participants may ascertain to what extent they have accomplished the proposed aims and objectives. 2. Developing the basic content of a module, following the formal guidelines provided in the specific guide, in accordance with the outline supplied. It should be remembered that didactic materials are neither a book nor an article, rather learning-oriented material. To develop content, it is useful to bear the following in mind: • The activation of previous knowledge. Each didactic unit should begin with questions that evoke the previous knowledge required for the unit. • Offering a real context to exercise competencies. An initial situation or practical case must be created in which the participant takes the initiative, based on alternative decisions put to them. Ideally, the case or situation should be kept alive throughout the didactic unit. • Organising content around its application. The way in which content is introduced shall depend on the decision-making process of each participant, i.e., within a non-lineal pedagogic structure. However, it is possible to always offer an access menu to a sequential presentation of the contents themselves. • Favouring the transfer to other contexts and situations. Each new concept should be accompanied by a mini-case, whether it is solved or not, in which the context changes with 21 regard to the situation described in the initial practical case. Changes should especially be highlighted in order to favour this transfer. • Putting learning to the test. The didactic units should contain a system of self-assessment with broad answers referring to the text. They should therefore meet the following criteria: o Given the nature of the participants, self-assessment exercises should be set at the end of each logical learning sequence. One sequence should not last, under average circumstances, more than 15 minutes – which would be the equivalent, therefore, of some three to five pages of text, depending on the degree of difficulty. o Students must be able to ascertain immediately by themselves whether or not their answers are correct; this forces the suitable presentation of the solutions and their alternatives. o Students must be able to verify whether they have achieved the objectives established in the didactic unit. Self-assessment should always be understood in relation with the quality and quantity of the educational objectives achieved. • Creating opportunities for collaborative learning. The course methodology will actively encourage students to find the opportunities to collaborate on tasks and exercises to achieve the desired learning outcomes. Formally, there are two ways to realise this purpose: o The discussion forum, whose didactic characteristics are discussed later. o The final essay of each module, excepting the Dissertation module, which should be the result of teamwork, and worth at least half of the credits • Continually motivating. The best motivation methods are aimed at each participant personally, and this can only be done via messages from the teacher using e-mail –see below. In any case, the units may contain elements for self-motivation, which attempt to keep students’ interest through captions in 22 the body of the text. For example, illustrations, cartoons and comic strips, press cuttings, ironic comments, questions that are left unsolved until the following section, etc. 3. Compiling complementary didactic materials. All units require complementary reference material, which in an e–learning programme should be put within reach of the course participant. These materials should be included as annexes and be supplied royalty-free. 4. Planning those activities, which the student must perform. This is the most difficult part given that it consists of designing an itinerary of activities that will supposedly lead the participant to acquire or exercise the competencies that must be demonstrated to successfully complete the module. These activities must be closely related to the case study or situation proposed at the start of the module. 5. Proposing the final exam exercises. The exercises for the final assessment (test and essay) are to be prepared previously, but they must not be put at the students’ disposal until the time when each didactic unit is considered finished. 23 3.2. Development of the course During the development of the course, the teaching staff basically performs three functions: 1. Motivation 2. Dealing with enquiries 3. Fomenting debate or the discussion forum Didactic guidelines 1. Welcome message. The teaching staff should always keep ahead of the students. Given that study time is very short, it is important for the teacher to provide in advance, at the beginning of each unit, welcome or guidance message. This message should highlight the most relevant aspects of the unit and, whenever possible, its relationship with the previous and the following units. The message should start with a professional question whose reply will depend on students’ command of the didactic unit. 2. Message of reassurance. Motivation is of utmost importance in e–learning. For this reason, it is important for the teacher to send a message every week, before the weekend, reminding students of the relevance of the subject matter and insisting that, if they are having any difficulties with the material, the teacher is at their disposal. 3. How to deal with e-mail enquiries. Enquiries by e-mail are a substantial part of the teaching task throughout the development of the course and, to some extent, provide the student with an insight into the teacher’s ways. For this reason, special attention should be paid to the following. 1. Replies should be supplied immediately (within 24 hours). If the enquiry is particularly tricky, the participant should receive an indication as to when to expect the corresponding reply and make them aware of the inherent difficulty in the reply. 2. It is often useful to publish the question and the reply for all participants and add it to the FAQ system. Keep an eye on e-mail 24 3. It is also useful to establish a discussion board where such questions can be posted. This can be used to encourage students to help each other, and research their own and each other's questions. The tutor can then moderate replies and solutions, and a meaningful learning experience for the group can be constructed from an initial difficulty of one individual student. Much like a face-to-face seminar: the tutor sets small tasks or exercises requiring relatively brief written, but researched, answers or solutions on a weekly basis. These too are posted on a discussion board and comment, suggestions etc., are invited from the group. This serves several useful pedagogic functions: it encourages the development of research skills; provides continuous practice at written presentation; similarly it prepares students for publicising their work for comment and criticism, getting them used to the idea that academic study is always, work in progress and under constant revision; it ensures students keep up with the learning material and timetable of study; it provides an early warning system of possible problems among individual students and conversely, offers an indication of student progress; it achieves the demand of group, co-operational and competitive, learning in one go, similar to the environment we actually work in as professional academics; and, vitally, it provides a revision database that students can use later in their studies. 4. If the enquiry can be replied to through the material itself, the student should be referred to the corresponding section, without any reproach. 5. Whenever possible, the means of going into greater depth on the reply should be provided (i.e., references to: articles, books, websites, etc.). 6. The language and expressions used must be carefully and sensitively chosen. The participant may receive the reply after a hectic day’s work and may be suffering from a great deal of stress. 4. How to lead a debating forum. A debating forum can be one of the most critical elements of the course, due to the exchanges between expert professionals from a variety of different contexts. This is probably the most difficult aspect of the development of the course. 25 1. The forum is always started by the teacher and based Leading debate fora upon a situation or practical case, which the teacher describes with an opening intervention. 2. For the smooth running of the forum, it is essential for there to be just an initial question, which should be formulated so that it cannot be misinterpreted and is easily understood. Any connection between the question and the unit material should be clear and, if necessary, be given special consideration by the teacher. 3. The role of the teacher at the forum can be summed up in three broad aspects: – to keep students’ interest through suggestive interventions – it is often useful to adopt the role of the devil’s advocate. – to periodically sum up the state of the discussion. Participants’ interventions are usually lengthy and it is quite easy to lose the thread, from one day to the next. – to focus the evolution of students’ interventions around the subject being analysed. The teacher should ensure that the debate remains within the didactic objectives set. An intervention may often draw attention to an absolutely collateral, secondary element that ends up stimulating interest due to its novelty. The teacher should attempt to steer the debate back on course. – to bring the forum to a close. The teacher should bring the forum to a close by summing up the interventions and concluding with regard to the initial situation. 4. The frequency of connections. As a general rule, bearing all of the above in mind, the teaching staff shall connect to the system on a daily basis, and will do their best to reply within 24 hours to all enquiries received, and failing this, announcing when they will do so. Connect every day! 26 3.3. Assessment The teaching staff disposes of a variety of tools for student assessment: 1. The final test of each unit (4 per module). 2. The essay-report, which is sent at the end of each module. 3. Participation in the debate. 4. Other information generated by the system. Didactic guidelines 1. Definition of objectives. Each module shall contain an expression of the competencies the student will have acquired by the conclusion. This expression will be as operative as possible, so that the student is aware of the degree of compliance with the proposed objective. 2. Clarity of assessment criteria. Each module must offer the student a clear indication as to the relative weighting that each of the module’s elements has towards the final marks. The student must be able to understand how the final marks are broken down. 3. Immediate feed–back. In an e–learning system, feed–back needs to be as quick as possible. For this reason: a. As already indicated, units must contain multiple opportunities for self-assessment. b. The results of the final exam should be sent to the student within 24 hours whenever possible. c. The assessment concerning the final essay should be as immediate as possible and reasonable. Upon receipt of the essay, the teacher shall reply to the student to acknowledge receipt, providing the latter with the date when the corresponding mark will be sent. 4. Assessment. The final mark for each unit shall be accompanied by a personalised comment. If the student has not come up to the expected level in some competencies, he or she shall be offered an opportunity to catch up –extra exercises, etc.- to allow him to do so. He or she must not be prevented from having the opportunity to do so, always within the time frame established for the course. What must feed-back be like?