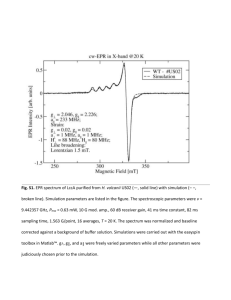

life cycle cost analysis - The Eno Center for Transportation

advertisement