Birth After Previous Caesarean Section (C

advertisement

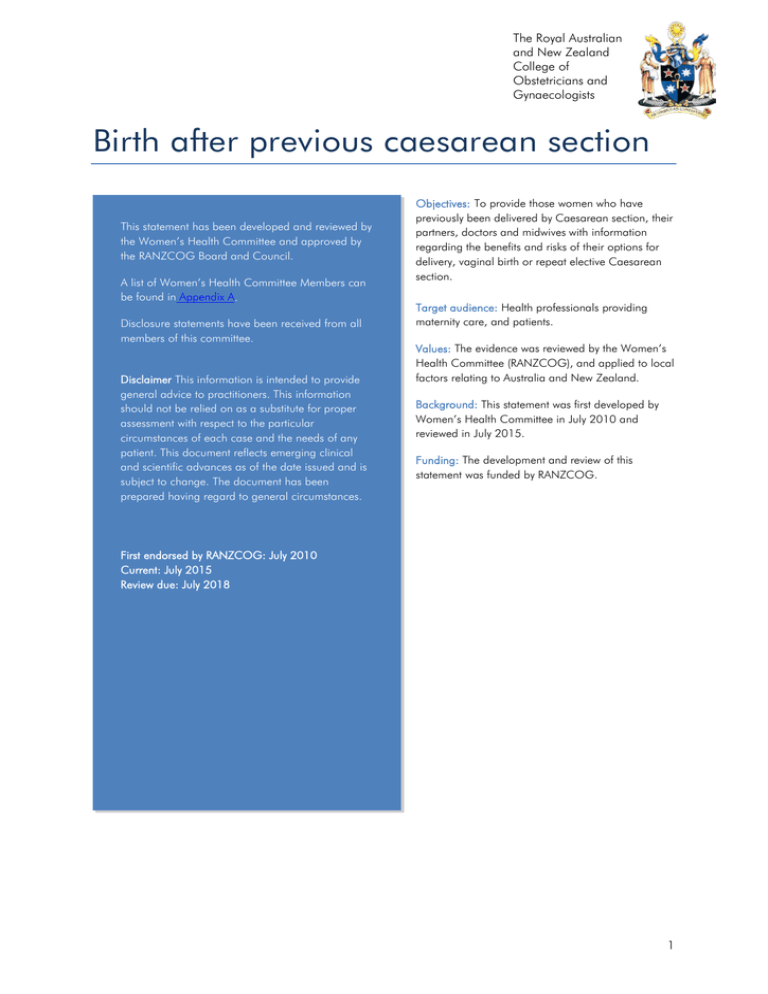

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Birth after previous caesarean section This statement has been developed and reviewed by the Women’s Health Committee and approved by the RANZCOG Board and Council. A list of Women’s Health Committee Members can be found in Appendix A. Disclosure statements have been received from all members of this committee. Disclaimer This information is intended to provide general advice to practitioners. This information should not be relied on as a substitute for proper assessment with respect to the particular circumstances of each case and the needs of any patient. This document reflects emerging clinical and scientific advances as of the date issued and is subject to change. The document has been prepared having regard to general circumstances. Objectives: To provide those women who have previously been delivered by Caesarean section, their partners, doctors and midwives with information regarding the benefits and risks of their options for delivery, vaginal birth or repeat elective Caesarean section. Target audience: Health professionals providing maternity care, and patients. Values: The evidence was reviewed by the Women’s Health Committee (RANZCOG), and applied to local factors relating to Australia and New Zealand. Background: This statement was first developed by Women’s Health Committee in July 2010 and reviewed in July 2015. Funding: The development and review of this statement was funded by RANZCOG. First endorsed by RANZCOG: July 2010 Current: July 2015 Review due: July 2018 1 Table of contents 1. Terminology ............................................................................................................................. 3 2. Patient Summary ....................................................................................................................... 3 3. Summary of recommendations ................................................................................................... 4 4. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 5 5. Discussion and recommendations............................................................................................... 6 5.1 Past history and suitability for VBAC.......................................................................................... 6 5.2 Success Rates ......................................................................................................................... 7 5.3 Benefits and risks of VBAC....................................................................................................... 8 5.4 Benefits and risks of ERCS at 39 weeks ..................................................................................... 8 5.5 Uterine Rupture ...................................................................................................................... 9 5.6 Perinatal Mortality ................................................................................................................ 10 5.7 Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE) .................................................................................. 10 5.8 Risks associated with ERCS .................................................................................................... 11 5.9 Intrapartum Recommendations .............................................................................................. 12 5.10 Induction and augmentation in labour .................................................................................. 14 6. Special Circumstances ............................................................................................................. 15 6.1 Trial of labour after more than one previous Caesarean section ............................................... 15 6.2 Twin Gestation ..................................................................................................................... 15 6.3 Midtrimester delivery ............................................................................................................. 16 7. Conclusion ............................................................................................................................. 16 USEFUL LINKS USED IN THE WRITING OF THIS STATEMENT ........................................................... 17 LINKS TO OTHER COLLEGE STATEMENTS ..................................................................................... 17 REFERENCES ................................................................................................................................. 19 Appendices ................................................................................................................................... 23 Appendix A Maternal Morbidity of Women Who Had Caesarean Deliveries Without Labour 59 .......... 23 Appendix B Outcomes of VBAC comparing patients with one previous caesarean section with those multiple previous caesarean sections. ........................................................................................... 24 Appendix C Women’s Health Committee Membership ................................................................... 26 Appendix D Overview of the development and review process for this statement .............................. 26 Appendix E Full Disclaimer .......................................................................................................... 28 Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 2 1. Terminology VBAC: Successful vaginal birth following labour in a woman who has had a prior Caesarean section delivery. PLANNED VBAC: Planned labour with a view to safe vaginal birth in a woman who has had a prior Caesarean section delivery. Also referred to by some authors as Trial of Labour (TOL) or Trial of Labour after Caesarean (TOLAC) or Next Birth after Caesarean (NBAC). ERCS: Elective repeat Caesarean section. Planned Caesarean section in a woman who has had one or more previous Caesarean sections. PERINATAL MORTALITY: The combined number of still births (antepartum and intrapartum) and neonatal deaths (death of a live infant from birth to the age of 28 days). HYPOXIC ISCHAEMIC ENCEPHALOPATHY (HIE): Neurological changes caused by lack of sufficiently oxygenated blood perfusing brain tissue resulting in compromised neurological function manifesting during the first few days after birth. HIE may be associated with multiple organs damaged by similar perfusion injuries. • NEONATAL RESPIRATORY MORBIDITY: The combined rate of transient tachypnoea of the newborn (TTN) and respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). UTERINE RUPTURE: A disruption of the uterine muscle extending to and involving the uterine serosa or disruption of the uterine muscle with extension into bladder or broad ligament. UTERINE SCAR DEHISCENCE: A disruption of the uterine muscle with intact uterine serosa. PLACENTA ACCRETA: Densely adherent placenta due to abnormally deep invasion of the placenta into the uterine muscle and sometimes growing through the full thickness of the uterine wall to the outside of the uterus. LUSCS: Lower Uterine Segment Caesarean Section. RCOG: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. ACOG: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. SOGC: Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. 2. Patient Summary Many women will need to decide on the mode of birth for subsequent pregnancies after a caesarean section. Each option – either labour with a view to safe vaginal birth, or planned Caesarean section - has both potential risks and benefits. Each individual woman’s preferences and risk profiles will be different. Involvement of the woman and her family in this decision making is strongly supported. Those who provide maternity care - doctors and midwives - need to provide women and their partners with accurate and relevant information. It can be challenging to explain and understand the risk of complications which occur rarely, but with very serious consequences when they happen. Attempting vaginal birth after a previous Caesarean section carries the additional risk for mother and baby of uterine scar rupture, an event that occurs approximately five to seven times in every 1000 attempts. If this does occur, there is approximately a one in seven chance of serious adverse outcome (death or brain injury) for the baby. When repeat elective Caesarean section is chosen there are the risks associated with major surgery, and a commitment to future Caesarean delivery is Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 3 likely. As the number of her previous Caesarean section deliveries increases, so does the risk of rare but serious complications. The benefits and risks of each birth option and the factors affecting the chances of success for planned VBAC are discussed in this statement. An agreed plan of management for birth should be made during a woman’s pregnancy and be documented in the medical record. Women who choose to labour with a view to the safest possible vaginal delivery should be managed in an obstetric unit with trained staff and the appropriate equipment to monitor the mother’s and fetus' wellbeing continuously throughout the labour, and has the facility to proceed to urgent Caesarean section if required. Epidural analgesia may be used. Some special circumstances such as women who have had more than one Caesarean delivery, twin pregnancy and induction of labour in mid trimester are discussed. 3. Summary of recommendations Recommendation1 Grade Early in the postnatal period following a primary Caesarean delivery, women should be offered the opportunity to be debriefed and to discuss their birth experience, as well as their potential suitability for planned VBAC in future pregnancies. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 2 Grade Women with a prior history of an uncomplicated lower segment Caesarean section, in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy, should be given the opportunity to discuss the birth options of planned VBAC or elective Caesarean section early in the course of their antenatal care. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 3 Grade The risks and benefits of the birth options, considered in conjunction with an individual woman’s chances of success for VBAC, should be discussed with the patient and documented in the medical record. The provision of a patient information leaflet or other similar resource at the consultation is recommended. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 4 Grade Respect should be given to the woman’s right to be involved in the decision making regarding mode of birth, considering her wishes, her perception of the risks and her plans for future pregnancies. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 5 Grade Attempts should be made, where possible, to check the operative record of the previous Caesarean section, its indication and post-operative course. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 6 Grade Women considering options for birth after a previous Caesarean section should be informed that ERCS may increase the risk of serious complications in future pregnancies. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 7 Grade A final decision regarding mode of birth should be agreed between the woman and her obstetrician (and midwife where appropriate) before the expected/planned delivery date (ideally by 36 weeks gestation). A plan in the event of labour starting prior to the scheduled date should be agreed and documented. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 8 Grade Women should be advised that a planned VBAC should be conducted in a suitably staffed and equipped delivery suite, with continuous intrapartum care and monitoring and with available resources for urgent Caesarean section and Consensus-based recommendation Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 4 advanced neonatal resuscitation should complications such as scar rupture occur. Recommendation 9 Grade Continuous intrapartum care is required to monitor progress and to enable prompt identification and management of uterine scar rupture. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 10 Grade Women should be advised to have continuous electronic fetal monitoring following the onset of uterine contractions and for the duration of the planned VBAC. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 11 Grade Epidural anaesthesia is not contraindicated in a planned VBAC. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 12 Grade Early diagnosis of the serious complication of uterine scar rupture followed by expeditious laparotomy and resuscitation is essential to reduce the associated morbidity and mortality for mother and infant. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 13 Grade If induction of labour is required in a patient with a previous Caesarean section, the benefits and risks of planned VBAC should be reconsidered with alternatives discussed. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 14 Grade Prostaglandins are not recommended for the induction of planned VBAC at term. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 15 Grade Augmentation of labour with oxytocin in planned VBAC should be performed with caution, and should involve a consultant-led discussion with the risks and benefits discussed with the patient then documented in the clinical record. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 16 Grade Pregnancy after Caesarean section should be subject to multi-disciplinary clinical audit, including assessment of the number of women opting for planned VBAC versus ERCS as well as the number achieving VBAC. Quality of adherence to agreed protocols should form part of the clinical audit. Consensus-based recommendation 4. Introduction In recent decades the Caesarean section rates have continued to rise; to 32% of births in Australia in 2011 and 23.6% of births in New Zealand in 2010.1, 2 As a consequence there are increasing numbers of women who need advice regarding options for birth in subsequent pregnancies. Each option, elective Caesarean section or labour with a view to vaginal birth, has its benefits and risks. Patient differences give rise to a variation of patient preference, risk spectrum and of success rates for vaginal birth. Patients and clinicians conjointly need to consider the options with a view to planning mode and place of birth for each mother who has had a previous Caesarean delivery. There are no large prospective randomised controlled trials assessing birth options.3 There are large numbers of reports which are mainly retrospective studies, predominantly originating in North America, the UK and Europe which provide some evidence of which to base decision making, but these are subject to variation both of population and management. There have been at least three Australian studies and two New Zealand studies reporting local outcomes.4-8 Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 5 5. Discussion and recommendations 5.1 Past history and suitability for VBAC 5.1.1 That a woman should be well informed regarding mode of birth after previous Caesarean section and have the right to have her wishes respected is strongly supported by RANZCOG and other similar professional bodies.9-11 5.1.2 It is appropriate that the counselling process begins after the primary caesarean section, ideally before discharge from hospital. Ideally, it should be conducted by the doctor who performed the caesarean section and, where appropriate, the midwife who cared for the patient during her labour. The reason for the caesarean section and any unexpected issues occurring before, during or after the surgery should be discussed, particularly any that would affect the woman’s suitability for VBAC in future pregnancies. Advice which could increase the success and safety of planned VBAC, such as an inter-delivery interval of at least 18 months and weight reduction for overweight and obese patients should be provided. 12-16 This debrief would also provide an opportunity to address any emotional needs, particularly for patients who found the experience traumatic. If a woman was not feeling ready for this discussion before discharge from hospital, a review early in the postnatal period would be worthwhile. 5.1.3 Studies of women who have faced the decision regarding mode of birth after previous caesarean delivery have reported that a significant number of women found the decision difficult – balancing their wishes against the interests of their child. 17 The potential risks and benefits need to be discussed in the context of the woman’s individual circumstances, including her personal motivation and preferences to achieve vaginal birth or ERCS, her attitudes to the risk of rare but serious adverse outcomes, her plans for future pregnancies and her chances of successful VBAC. Recommendation1 Grade Early in the postnatal period following a primary Caesarean delivery, women should be offered the opportunity to be debriefed and to discuss their birth experience, as well as their potential suitability for planned VBAC in future pregnancies. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 2 Grade Women with a prior history of an uncomplicated lower segment Caesarean section, in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy, should be given the opportunity to discuss the birth options of planned VBAC or elective Caesarean section early in the course of their antenatal care. Consensus-based recommendation Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 6 Recommendation 3 Grade The risks and benefits of the birth options, considered in conjunction with an individual woman’s chances of success for VBAC, should be discussed with the patient and documented in the medical record. The provision of a patient information leaflet or other similar resource at the consultation is recommended. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 4 Grade Respect should be given to the woman’s right to be involved in the decision making regarding mode of birth, considering her wishes, her perception of the risks and her plans for future pregnancies. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 5 Grade Attempts should be made, where possible, to check the operative record of the previous Caesarean section, its indication and post-operative course. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 6 Grade Women considering options for birth after a previous Caesarean section should be informed that ERCS may increase the risk of serious complications in future pregnancies. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 7 Grade A final decision for mode of birth should be agreed between the woman and her Obstetrician (and midwife where appropriate) before the expected/planned delivery date (ideally by 36 weeks gestation). A plan in the event of labour starting prior to the scheduled date should be agreed and documented. Consensus-based recommendation 5.2 Success Rates 5.2.1 There has been a wide range of success rates (23 - 85%) reported for those achieving vaginal birth following a planned VBAC.4, 6, 18-21 Published studies of the outcomes for women attempting VBAC report a likelihood of success of between 60 and 80% .10 A study from Middlemore Hospital in New Zealand reported a 73% success rate, and one from 14 Australian hospitals reported a success rate of 43%.6, 7 5.2.2 Factors affecting success FAVOURING SUCCESS Previous safe vaginal birth. Previous successful VBAC. Spontaneous onset of labour. Uncomplicated pregnancy without other risk factors. 5.2.3 REDUCING SUCCESS Previous Caesarean section for dystocia. Induction of labour. Coexisting fetal, placental or maternal conditions22 Maternal BMI greater than 30 Kg/m2. Fetal macrosomia of 4 kg or more. Advanced maternal age. Short stature. More than one previous Caesarean section. Risk factors associated with an increased risk of uterine scar rupture (see below). Previous vaginal birth, especially successful VBAC, is the strongest predictor of success, with VBAC rates of 87-91% reported in that group.7, 18, 19, 23 Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 7 5.2.4 Induced labour, no previous vaginal birth, a BMI greater than 30 Kg/m2, and previous Caesarean section for dystocia are factors that all reduce the success rate; Landon reported if all four are present then the success rate was only 40%.18 5.2.5 For the mordidly obese patient (BMI>40 Kg/m2) the chances of a unsuccessful VBAC and of uterine rupture are significantly increased. Hiddard, in a prospective observational study of 14,142 patients undergoing VBAC, reported unsuccessful trial of labour in 15.2% of those of normal weight (1344 women) compared to 39.3% for those with a BMI≥40 Kg/m2 (1,344 women) (p< 0.001), with the incidence of uterine rupture/dehiscence being 0.9% compared to 2.1% (p=0,03).24 5.2.6 Other factors which have been reported to adversely affect success rates are gestational age beyond 41 weeks, fetal macrosomia, advanced maternal age, short stature, and fetal malpresentation.18-21, 25 Clinicians may find the online NICHD MFMU calculator for predicting successful VBAC useful. This resource can be accessed at: https://mfmu.bsc.gwu.edu/PublicBSC/MFMU/VGBirthCalc/vagbirth.html. This calculator estimates likelihood of VBAC success according to variables such as maternal age, BMI, and indication for previous Caesarean section, and is based on the equation published by NICHD MFM Units Network.26 While other factors may influence likelihood of success, clinicians may find this calculator useful when counselling patients regarding their individualised likelihood of success. 5.3 Benefits and risks of VBAC BENEFITS IF SUCCESSFUL VBAC Less maternal morbidity for index pregnancy and future pregnancies. Avoidance of major surgery. Earlier mobilisation and discharge from hospital. Patient gratification in achieving vaginal birth if this is desired. RISKS Increased perinatal loss compared with ERCS at 39 weeks(1.8 per 1000 pregnancies) Stillbirth after 39 weeks gestation (due to longer gestation). Intrapartum death or neonatal death (related to scar rupture in labour). HIE risk (0.7 per 1000). Related both to labour and vaginal birth and to scar rupture. Increase morbidity of emergency Caesarean section compared to ERCS if unsuccessful in achieving VBAC.27, 28 Pelvic floor trauma. 5.4 Benefits and risks of elective repeat Caesarean section at 39 weeks BENEFITS Avoid late stillbirth (after 39 weeks). Reduced perinatal mortality and morbidity (especially HIE) related to labour, delivery and scar rupture. Reduced maternal risks associated with emergency Caesarean section. Avoidance of trauma to the maternal pelvic RISKS Surgical morbidity and complications both with index pregnancy and further pregnancies. Increased risk of neonatal respiratory morbidity – low incidence ≥ 39 weeks gestation. Associated with lower rates of initiating breast feeding 29-31 Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 8 floor. Convenience of planned date for birth. 5.5 Uterine Rupture 5.5.1 Uterine rupture in an unscarred uterus is extremely rare, with incidence rates estimated at 0.52.0 per 10,000 deliveries, and occurrence mainly confined to multiparous patients in labour. 32 The incidence of scar rupture in a patient undergoing VBAC has been reported between 22 and 74 per 10,000 births.9, 33, 34 5.5.2 Chauhan et al reviewed maternal and perinatal complications from 142,075 patients who attempted vaginal birth after Caesarean section delivery. 35 They reported a uterine rupture rate of 6.2/1,000 trials of labour. The uterine rupture-related complication rate was 1.5 per 1,000 for pathological fetal acidosis (a cord pH < 7.00), 0.9/1000 for hysterectomy, 0.4/1,000 for perinatal death, and 0.02/1,000 for maternal death. These figures are consistent with a large Australian retrospective analysis and review of 10 international series where the likelihood of uterine rupture of attempted vaginal delivery after previous lower segment Caesarean section was estimated at 5/1,000, and the perinatal death from uterine rupture at 0.7/1,000 women attempting VBAC.4 Landon, in a prospective observational study from 19 academic centres in the United States, reported a symptomatic uterine rupture rate of 7/1,000 from a total of 17,898 women who planned VBAC, and the occurrence of HIE in seven babies related to uterine rupture (0.4/1000). 33 The overall complication rates related to scar rupture per 1000 women attempting VBAC for the three series is summarised in the table below: 4 33, 35 TABLE 1: The complication rates related to scar rupture per 1000 women attempting VBAC4, 33, 35 COMPLICATION Uterine rupture Perinatal death Maternal death Major maternal morbidity • Hysterectomy • Genitourinary injury • Blood transfusion Major perinatal morbidity • Fetal acidosis (cord pH <7.0) • HIE RISK/ 1,000 ATTEMPTED VBAC 5-7/1,000 0.4-0.7/1000 0.02/1000 Approximately 3/1000 0.5-2/1000 0.8/1000 1.8/1000 Approximately 1/1000 1.5/1000 0.4/1000 5.5.3 A previous vaginal birth reduces the risk of uterine scar rupture. 36, 37 5.5.4 The risk of uterine rupture is increased with previous classical Caesarean section (20 to 90/1,000), previous ‘inverted T’ or ‘J’ incisions (19/1,000), and low vertical incision (20/1,000). 9 Obtaining the record of the operative note from a previous Caesarean section to define the nature of previous scar and any significant uterine tears may be helpful in assessing the risk of future uterine rupture. A higher incidence of scar rupture has also been reported with induction of labour and augmentation of labour.5, 38-41 The risk of scar rupture is further increased when prostaglandins are used to induce labour.38-40 5.5.6 A two to three-fold increase in the incidence of scar rupture has been reported if the pregnancy interval has been less than 18 months12 or less than 24 months.12, 15 There is conflicting Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 9 evidence as to whether single layer compared to double layer uterine closure increases the risk of scar rupture in subsequent planned VBAC 12, 42 5.5.7 Unfortunately, ultrasound measurement of myometrial thickness has not been demonstrated to be sufficiently predictive, or protective, of uterine rupture to be useful in clinical practice. Studies measuring the lower segment thickness by ultrasound in late pregnancy have reported a low incidence of subsequently detected scar defects (rupture or dehiscence) occurring with a greater frequency in patients whose ultrasound reported a very thin lower segment; however there are many other factors that can affect the incidence of uterine scar rupture.43-47 5.6 Perinatal Mortality Women electing trial of labour have an increased risk of perinatal mortality compared to those undergoing ERCS. 48 However, much of this is attributable to the often understated background rate of perinatal death after 39 weeks gestation. Where 0.4/1,000 may have a perinatal death related to uterine rupture, a further 1.4/1,000 may be expected to have an antenatal, intrapartum or neonatal death after 39 weeks gestation.35, 49 It is appropriate that this increase in perinatal mortality (1.8/1,000) be acknowledged in counselling about birth options, even though mostly not a direct consequence of uterine rupture. 5.7 Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE) Landon reported 12 cases of HIE amongst 17,898 women undergoing planned VBAC (0.7/1,000), seven cases were related to uterine rupture and five to hypoxia in labour. 33 In the same study there were no cases of HIE in 15,801 women undergoing ERCS (p < 0.001). Children with long term neurological impairment following uterine rupture have also been reported but the frequency is almost impossible to determine given the absence of long term follow-up data in these retrospective series.50, 51 Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 10 5.8 Risks associated with ERCS While Elective Caesarean section reduces the risks of some serious adverse outcomes for the baby, the mother is exposed to surgical risks which increase with each Caesarean section that she has. 5.8.1 Neonatal Perspective Elective Caesarean section removes the risk of late perinatal loss of the baby (1.8/1000), the risk of HIE related to labour (0.7/1000) and reduces the risk of significant traumatic fetal injury. The risk of fetal injury at elective Caesarean delivery is 5/1000, with the majority (71%) being a superficial skin laceration.52 The risk of fetal intracranial injury at ERCS is very low (1:2750) when compared with assisted vaginal delivery, forceps (1:664) and vacuum (1:860), and spontaneous vaginal delivery (1:1900).53 The risk of brachial plexus injury from shoulder dystocia is significantly lower at Caesarean section.54 When compared to vaginal birth, Caesarean section without labour has been associated with increased neonatal respiratory morbidity including transient tachypnoea of the newborn, surfactant deficiency and pulmonary hypertension. This incidence is inversely related to gestation and after 40 weeks gestation there is no difference in the incidence.55 In response to this, deferring elective caesarean delivery in uncomplicated singleton pregnancies until 39 weeks gestation or later is recommended by some international obstetric bodies.56-58 5.8.2 Maternal Perspective Repeat elective Caesarean section exposes the mother to surgical risk in her current pregnancy, the risk increasing with each subsequent Caesarean section. In a large prospective study of 30,132 women who had caesarean delivery without labour, a total of 1202 significant complications occurred in 15,808 patients electively undergoing their second Caesarean section. As the patient’s number of caesarean deliveries increased there was statistically significant increase in the serious complications of severe haemorrhage (requiring more than four units of blood transfused), hysterectomy, bladder and bowel injury and requirement for postoperative ventilation.59 Details of these findings are presented in Appendix A. 5.8.3 Subsequent Pregnancies An important issue to be considered in the decision analysis for many women is the intended future family size. Silver found that placenta accreta was present in 0.24%, 0.31%, 0.57%, 2.1% and 2.3% and 6.7% of women undergoing their first, second, third, fourth, fifth and six or more Caesarean section deliveries respectively. 59 This is a consequence both of an increasing incidence of placenta praevia with repeated Caesarean sections and an increased likelihood of placenta accreta where the placenta is located over the uterine scar. The abnormally adherent placenta associated with placenta accreta is a potentially life threatening obstetric complication that may require interventions such as hysterectomy and high volume blood transfusion. 5.8.4 Emergency caesarean risk compared to elective caesarean section The maternal morbidity associated with emergency Caesarean section is significantly greater than rates reported for elective Caesarean section. Severe complications were reported in 179/1355 (13.2%) emergency Caesarean sections, compared with 80/1,141 (7%) of those delivered by elective Caesarean section (p<0.001) in a prospective multicentre study from Finland.27 Similar results were reported in a large Canadian study of nulliparous patients comparing outcomes of 17,714 women in spontaneous labour at term with 721 women delivered by elective Caesarean section. 28 This increased risk of associated with the emergency Caesarean delivery needs to be considered, especially for those patients with relatively low chance of successful VBAC, and particularly for those women with co-existing medical morbidities. Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 11 5.8.5 Impact on the initiation of breastfeeding Several studies have demonstrated significantly lower rates of successful initiation of breast feeding among women having ERCS compared to those who delivered vaginally or who have attempted vaginal birth.29-31 It is difficult to adjust for all potential confounding variables that may contribute to these results. Nevertheless, in view of these findings it is recommended that all possible steps are taken to assist women having caesarean section to initiate breast feeding. This includes promoting skin to skin contact in theatre and supporting women to breast feed as soon as practicable after delivery, including in recovery. 5.9 Intrapartum Recommendations Recommendation 8 Grade Women should be advised that a planned VBAC should be conducted in a suitably staffed and equipped delivery suite, with continuous intrapartum care and monitoring and with available resources for urgent Caesarean section and advanced neonatal resuscitation should complications such as scar rupture occur Consensus-based recommendation 5.9.1 All women electing to labour after previous Caesarean section should have ready access to Obstetric, Neonatal, Paediatric, Anaesthetic, operating theatre and resuscitation services (including availability of blood products) in the event that complications occur. 5.9.2 Where, by virtue of remote location, these on-site services cannot be provided, patients should be informed of limitations of services available and the implications for care should a uterine rupture occur. In most circumstances this will result in either an elective repeat Caesarean section or alternatively antenatal transfer to a centre with more comprehensive services for a trial of labour. Recommendation 9 Grade Continuous intrapartum care is required to monitor progress and to enable prompt identification and management of uterine scar rupture. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 10 Grade Women should be advised to have continuous electronic fetal monitoring following the onset of uterine contractions for the duration of the planned VBAC. Consensus-based recommendation 5.9.3 A woman undergoing planned VBAC should be assessed in early labour. Members of the care team should be notified in a timely manner of the admission and of the relevant clinical circumstances. 5.9.4 There should be continuous midwifery support and continuous electronic fetal monitoring. 5.9.5 Intravenous access should be established once labour is established and blood sent for group & save with access to prompt crossmatch if required. 5.9.6 Oral intake should be restricted to clear fluids because of the greater than normal probability of needing an immediate Caesarean section under general anaesthetic. Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 12 5.9.7 A trial of labour mandates vigilant assessment of progress of labour with vaginal examinations at least four hourly in the active phase of labour and more frequently as full dilatation approaches. Two hourly assessments from 7cm dilated can be helpful to detect a secondary arrest of labour. There needs to be evidence of progress in labour in both first and second stage. Lack of progress should trigger clinical reassessment by an experienced obstetrician. Recommendation 11 Grade Epidural anaesthesia is not contraindicated in a planned VBAC. Consensus-based recommendation 5.9.8 Any concerns that epidural anaesthesia may mask symptoms of uterine rupture are not considered sufficient to contraindicate epidural use. In the NICHD study, planned VBAC success rates were higher among women who received epidural anaesthesia compared to those who did not (73% verses 50%). 18 Recommendation 12 Grade Early diagnosis of the serious complication of uterine scar rupture followed by expeditious laparotomy and resuscitation is essential to reduce the associated morbidity and mortality for mother and infant. Consensus-based recommendation 5.9.9 RCOG guidelines state, “There is no single pathognomic clinical feature that is indicative of uterine rupture but the presence of any of the following peri-partum should raise the concern of possibility of this event Abnormal CTG (present in 55-87% of cases). Severe abdominal pain especially persisting between contractions. Chest pain or shoulder tip pain. Sudden onset of shortness of breath. Acute onset of scar tenderness. Abnormal vaginal bleeding or haematuria. Cessation of previous efficient uterine activity. Maternal tachycardia, hypotension or shock. Loss of station of the presenting part. 9” Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 13 5.10 Induction and augmentation in labour Recommendation 13 Grade If induction of labour is required in a patient with a previous Caesarean section the benefits and risks of a planned VBAC should be reconsidered with alternatives discussed. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 14 Grade Prostaglandins are not recommended for the induction of planned VBAC at term. Consensus-based recommendation Recommendation 15 Grade Augmentation of labour with Syntocinon in planned VBAC should be performed with caution and be a consultant led discussion with the risks and benefits discussed with the patient then documented in the clinical record. Consensus-based recommendation 5.10.1 Induction of labour for maternal or fetal indications remains an option for women undergoing planned VBAC, however induction of labour reduces the success rate of achieving VBAC and increases the rate of uterine rupture. Induced labour is less likely to result in VBAC than spontaneous labour and an unfavourable cervix at induction decreases the chances of success.18, 40, 41, 60-63 5.10.2 In the large NICHD study of 17,898 women undergoing planned VBAC, the rates of intrapartum Caesarean section were 33%, 26% and 18% for induced, augmented and spontaneous labour groups respectively. The risk of uterine rupture per 10,000 planned VBAC’s was 102, 87, and 36 for induced, augmented and spontaneous labour groups.18, 33 5.10.3 Several studies have reported high rates (1.4 to 2.45%) of uterine rupture when labour has been induced using prostaglandins. 33, 38, 40 5.10.4 Information regarding the effectiveness and safety of transcervical catheters in planned VBAC is limited due to small sample sizes in the studies and valid conclusions are not possible.3 Two studies showed no risk of uterine rupture, whereas another reported an increased risk compared to women in spontaneous labour.20, 40 64 It is not clear whether any increased risk may be associated with an unfavourable cervix. 5.10.5 The use of oxytocin for augmentation of contractions, separate from induction of labour during planned VBAC, has been examined in several studies. Some have found an association between oxytocin augmentation and the uterine rupture where others have not.5, 33, 62, 63 In an Australian retrospective cohort study Dekker reported a 14 fold difference in the adjusted odds ratio for uterine rupture in planned VBAC patients in spontaneous onset of labour augmented with Syntocinon (12/628, 1.9%) compared to those without augmentation with Syntocinon (16/8221, 0.19%). 5.10.6 The decision to augment labour in planned VBAC appropriately should involve a consultant Obstetrician after clinical assessment of the case and discussion with the patient. Oxytocin should be titrated in such a way that adequate uterine activity is obtained but that there be no more than four contractions in 10 minutes. Careful cervical assessments, preferably by the same person, are required to show adequate progress thereby allowing augmentation to continue. The interval for serial vaginal examinations and selected parameters of progress that would necessitate discontinuing the labour should be consultant led decisions. Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 14 5.10.7 When informing a woman about induction and/or augmentation of labour, clear information regarding potential risks and benefits should be provided. Some women who are contemplating future pregnancies may accept short term additional risks associated with induction and/or augmentation in view of the reduced risk of serious complications for future pregnancies if they achieve a successful VBAC. 6. Special Circumstances 6.1 Trial of labour after more than one previous Caesarean section Studies comparing outcomes of planned VBAC for patients who have had two or more Caesarean sections generally have reported significantly lower success rates for achieving VBAC, higher rates of uterine rupture or scar dehiscence, and a greater incidence of major maternal morbidity when compared to patients with only one previous Caesarean section. A meta-analysis published in 2009 reported a significantly lower success rate for VBAC (71% vs 77%,p<0.001) and higher rupture rate (1.6% vs 0.7%, p<0.001) when the outcomes of planned VBAC after two previous caesarean sections were compared to those patients with one previous caesarean section. The meta-analysis reported a similar maternal morbidity for the patients undergoing VBAC after two previous caesarean sections compared with those undergoing a third ERCS.65 The details of some individual studies are summarised in Appendix B. Attitudes of Obstetricians and patients may vary in different regions. RCOG state that a patient with two previous uncomplicated caesarean sections in an uncomplicated pregnancy at term, “who has been fully informed by consultant Obstetrician may be considered suitable for planned VBAC”. 9 However, RCOG recommends that three previous Caesarean sections is a contraindication to planned VBAC. SOGC state “available data suggests that a trial of labour with more than one previous Caesarean section is likely to be successful, but is associated with a higher risk of uterine rupture”.11 6.2 Twin Gestation A cautious approach is advocated in twin pregnancies who are considering planned VBAC. There is some uncertainty regarding the safety and efficacy of planned VBAC in a twin pregnancy. Success rates of vaginal birth of between 64% and 76% without an increase in scar rupture or perinatal morbidity have been reported in three small studies; Varner (n=412), Cahill (n=535) and Miller (n=210). 66-68 The largest study reported a successful VBAC rate of 45% of 1850 twin pregnancies undergoing planned VBAC and a scar rupture rate of 0.9%. This study did not provide any neonatal outcome data.69 Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 15 6.3 Mid-trimester delivery Patients who have previously been delivered by Caesarean section and require delivery in the mid-trimester due to fetal abnormality or fetal demise have three options: hysterotomy; dilatation and evacuation (D&E); or, medical induction of labour. There have been no randomised trials comparing the outcomes from these options. Misoprostol, a synthetic analogue of Prostaglandin E 1 , has been successful when used in the mid-trimester both for patients with an unscarred uterus and for those with a scarred uterus.70-72 Goyal, in a 2009 systematic review of 16 studies, reported a rupture rate of 1/2384 (0.04%) in patients with no uterine scar and 2/722 (0.28%) in patients with one or more prior Caesarean sections. When misoprostol was the sole agent used to induce labour (seven studies) there were no uterine ruptures in 256 patients with prior caesarean delivery. When the more recent studies of Gulec (2013) and Berghella (2009) are combined a scar rupture rate of 2/104 (1.9%) occurred in patients with one previous caesarean section and 3/79 (3.7%) in those with two or more caesarean sections. There has been a wide variation in dosage and method of administration of misoprostol in the reported series.71, 72 Due to the limitations of the studies available Dodd and Crowther in a Cochrane review 2010 entitled “Misoprostol for induction of labour to terminate pregnancy in the second or third trimester for women with a fetal abnormality or after intrauterine fetal death” stated “ important information regarding maternal safety, in particular the occurrence of rare outcomes such as uterine rupture, remains limited.”73 Use of misoprostol (alone or combined with mifepristone) to induce labour in the second trimester would appear to be a reasonable option in women with prior caesarean delivery. Another option is mechanical cervical ripening with a balloon catheter (alone or combined with mifepristone) and carefully monitored syntocinon induction of labour. The decision between these methods will be determined by gestational age, cervical favourability, number and type of caesarean section scar/s and clinician experience. These labours require close surveillance and senior clinical oversight. 7. Conclusion Recommendation 16 Grade Pregnancy after Caesarean section should be subject to multi-disciplinary clinical audit, including assessment of the number of women opting for planned VBAC versus ERCS as well as the number achieving VBAC. Quality of adherence to agreed protocols should form part of the clinical audit. Consensus-based recommendation Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 16 USEFUL LINKS USED IN THE WRITING OF THIS STATEMENT RCOG Greentop Guidelines No.45 (2007); Birth after Previous Caesarean section. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg4511022011.pdf. ACOG Clinical Management Guidelines (Vaginal Birth after Previous Caesarean Section 2010); http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Practice-Bulletins/Committee-on-PracticeBulletins-Obstetrics/Vaginal-Birth-After-Previous-Cesarean-Delivery. SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines; Guidelines for Vaginal Birth after Previous Caesarean Birth (2004); http://sogc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/155E-CPG-February2005.pdf. SA Perinatal Practice Guidelines; (Birth options after Caesarean Section); http://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/98d6ab804ee1e002ad49add150ce4f37/Birth +options+after+caesarean+sectionPPG_june+2014.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=98d6ab8 04ee1e002ad49add150ce4f37. LINKS TO OTHER COLLEGE STATEMENTS Intrapartum Fetal Surveillance Clinical Guideline (3rd edition) http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/doc/Intrapartum%20Fetal%20Surveillance%20Clinical%20Guideline%20%20Third%20Edition.html Placenta Accreta (C-Obs 20) http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/component/docman/doc_download/954-placenta-accreta-c-obs20.html?Itemid=946 Timing of Elective Caesarean Section (C-Obs 23) http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/component/docman/doc_download/956-timing-of-elective-caesarean-sectionat-term-c-obs-23.html?Itemid=946 Delivery of the Fetus at Caesarean Section (C-Obs 37) http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/component/docman/doc_download/970-delivery-of-the-fetus-at-caesareansection-c-obs-37.html?Itemid=946 Caesarean Delivery on Maternal Request (CDMR) (C-Obs 39) http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/component/docman/doc_download/972-caesarean-delivery-on-maternalrequest-cdmr-c-obs-39.html?Itemid=946\ Perinatal Anxiety and Depression (C-Obs 48) http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/component/docman/doc_download/1171-perinatal-anxiety-and-depression-cobs-48.html?Itemid=946 Consent and the Provision of Information to Patients in Australia regarding Proposed Treatment (C-Gen 02a) http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/component/docman/doc_download/899-consent-and-the-provision-ofinformation-to-patients-in-australia-regarding-proposed-treatment-c-gen-02a.html?Itemid=946 Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 17 Consent and the Provision of Information to Patients in Australia regarding Proposed Treatment (C-Gen 02b) http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/component/docman/doc_download/1460-consent-and-provision-ofinformation-to-patients-in-new-zealand-regarding-proposed-treatment-c-gen-02b.html?Itemid=946 Evidence-based Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynaecology (C-Gen 15) http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/component/docman/doc_download/894-c-gen-15-evidence-based-medicineobstetrics-and-gynaecology.html?Itemid=341 Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 18 REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Hilder L, Zhichao Z, Parker M, Jahan S, Chambers GM. Australian mothers and babies 2012. New Zealand Ministry of Health. Clinical Indicators. 2012. Available from: http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-maternity-clinical-indicators-2012. Jozwiak M, Dodd JM. Methods of term labour induction for women with a previous caesarean section, Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD009792. Appleton B, Targett C, Rasmussen M, Readman E, Sale F, Permezel M. Vaginal birth after Caesarean section: an Australian multicentre study. VBAC Study Group, Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;40(1):87-91. Dekker GA, Chan A, Luke CG, Priest K, Riley M, Halliday J, et al. Risk of uterine rupture in Australian women attempting vaginal birth after one prior caesarean section: a retrospective population-based cohort study, BJOG. 2010;117(11):1358-65. Crowther CA, Dodd JM, Hiller JE, Haslam RR, Robinson JS, Birth After Caesarean Study G. Planned vaginal birth or elective repeat caesarean: patient preference restricted cohort with nested randomised trial, PLoS Med. 2012;9(3):e1001192. van der Merwe AM, Thompson JM, Ekeroma AJ. Factors affecting vaginal birth after caesarean section at Middlemore Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand, N Z Med J. 2013;126(1383):49-57. Wise MR, Anderson NH, Sadler L. Ethnic disparities in repeat caesarean rates at Auckland Hospital, Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53(5):443-50. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Birth after Previous Caesarean section. 2007. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg4511022011.pdf. American College of Obstetricans and Gynaecologists (ACOG). Clinical Management Guidelines Vaginal Birth after Previous Caesarean Section. 2010. Available from: http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Practice-Bulletins/Committee-on-PracticeBulletins-Obstetrics/Vaginal-Birth-After-Previous-Cesarean-Delivery. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC). Guidelines for Vaginal Birth after Previous Caesarean Birth. 2004. Available from: http://sogc.org/wpcontent/uploads/2013/01/155E-CPG-February2005.pdf. Bujold E, Mehta SH, Bujold C, Gauthier RJ. Interdelivery interval and uterine rupture, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1199-202. Esposito MA, Menihan CA, Malee MP. Association of interpregnancy interval with uterine scar failure in labor: a case-control study, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(5):1180-3. Huang WH, Nakashima DK, Rumney PJ, Keegan KA, Jr., Chan K. Interdelivery interval and the success of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery, Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(1):41-4. Shipp TD, Zelop CM, Repke JT, Cohen A, Lieberman E. Interdelivery interval and risk of symptomatic uterine rupture, Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(2):175-7. Callegari LS, Sterling LA, Zelek ST, Hawes SE, Reed SD. Interpregnancy body mass index change and success of term vaginal birth after cesarean delivery, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(4):330 e1-7. Lundgren I, Begley C, Gross MM, Bondas T. 'Groping through the fog': a metasynthesis of women's experiences on VBAC (Vaginal birth after Caesarean section), BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:85. Landon MB, Leindecker S, Spong CY, Hauth JC, Bloom S, Varner MW, et al. The MFMU Cesarean Registry: factors affecting the success of trial of labor after previous cesarean delivery, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 Pt 2):1016-23. Smith GC, White IR, Pell JP, Dobbie R. Predicting cesarean section and uterine rupture among women attempting vaginal birth after prior cesarean section, PLoS Med. 2005;2(9):e252. Bujold E, Hammoud AO, Hendler I, Berman S, Blackwell SC, Duperron L, et al. Trial of labor in patients with a previous cesarean section: does maternal age influence the outcome?, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(4):1113-8. Coassolo KM, Stamilio DM, Pare E, Peipert JF, Stevens E, Nelson DB, et al. Safety and efficacy of vaginal birth after cesarean attempts at or beyond 40 weeks of gestation, Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(4):700-6. Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 19 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. Gregory KD KL, Fridman M et al. Vaginal birth after Cesarean : clinical risk factors associated withadverse outcome, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008(198):452-5. Gyamfi C, Juhasz G, Gyamfi P, Stone JL. Increased success of trial of labor after previous vaginal birth after cesarean, Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):715-9. Hibbard JU, Gilbert S, Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, et al. Trial of labor or repeat cesarean delivery in women with morbid obesity and previous cesarean delivery, Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):125-33. Hollard AL, Wing DA, Chung JH, Rumney PJ, Saul L, Nageotte MP, et al. Ethnic disparity in the success of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery, J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19(8):483-7. Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, Spong CY, Leveno KJ, Rouse DJ, et al. Development of a nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery, Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):806-12. Pallasmaa N, Ekblad U, Aitokallio-Tallberg A, Uotila J, Raudaskoski T, Ulander VM, et al. Cesarean delivery in Finland: maternal complications and obstetric risk factors, Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(7):896-902. Allen VM, O'Connell CM, Liston RM, Baskett TF. Maternal morbidity associated with cesarean delivery without labor compared with spontaneous onset of labor at term, Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(3):477-82. Regan J, Thompson A, DeFranco E. The influence of mode of delivery on breastfeeding initiation in women with a prior cesarean delivery: a population-based study, Breastfeed Med. 2013;8:181-6. Zanardo V, Savona V, Cavallin F, D'Antona D, Giustardi A, Trevisanuto D. Impaired lactation performance following elective delivery at term: role of maternal levels of cortisol and prolactin, J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(9):1595-8. Prior E, Santhakumaran S, Gale C, Philipps LH, Modi N, Hyde MJ. Breastfeeding after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of world literature, Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(5):1113-35. Ofir K, Sheiner E, Levy A, Katz M, Mazor M. Uterine rupture: risk factors and pregnancy outcome, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):1042-6. Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Leindecker S, Varner MW, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery, N Engl J Med. 2004;351(25):2581-9. Turner MJ, Agnew G, Langan H. Uterine rupture and labour after a previous low transverse caesarean section, BJOG. 2006;113(6):729-32. Chauhan SP, Martin JN, Jr., Henrichs CE, Morrison JC, Magann EF. Maternal and perinatal complications with uterine rupture in 142,075 patients who attempted vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: A review of the literature, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(2):408-17. Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, Spong CY, Leveno KJ, Rouse DJ, et al. Prediction of uterine rupture associated with attempted vaginal birth after cesarean delivery, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(1):30 e1-5. Zelop CM, Shipp TD, Repke JT, Cohen A, Lieberman E. Effect of previous vaginal delivery on the risk of uterine rupture during a subsequent trial of labor, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(5):11846. Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP. Risk of uterine rupture during labor among women with a prior cesarean delivery, N Engl J Med. 2001;345(1):3-8. Zelop CM, Shipp TD, Repke JT, Cohen A, Caughey AB, Lieberman E. Uterine rupture during induced or augmented labor in gravid women with one prior cesarean delivery, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(4):882-6. Ravasia DJ, Wood SL, Pollard JK. Uterine rupture during induced trial of labor among women with previous cesarean delivery, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(5):1176-9. Sims EJ, Newman RB, Hulsey TC. Vaginal birth after cesarean: to induce or not to induce, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(6):1122-4. Durnwald C, Mercer B. Uterine rupture, perioperative and perinatal morbidity after single-layer and double-layer closure at cesarean delivery, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):925-9. Rozenberg P, Goffinet F, Phillippe HJ, Nisand I. Ultrasonographic measurement of lower uterine segment to assess risk of defects of scarred uterus, Lancet. 1996;347(8997):281-4. Bujold E, Jastrow N, Simoneau J, Brunet S, Gauthier RJ. Prediction of complete uterine rupture by sonographic evaluation of the lower uterine segment, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(3):320 e16. Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 20 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62. 63. 64. 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. Naji O, Daemen A, Smith A, Abdallah Y, Saso S, Stalder C, et al. Changes in Cesarean section scar dimensions during pregnancy: a prospective longitudinal study, Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41(5):556-62. Asakura H, Nakai A, Ishikawa G, Suzuki S, Araki T. Prediction of uterine dehiscence by measuring lower uterine segment thickness prior to the onset of labor: evaluation by transvaginal ultrasonography, J Nippon Med Sch. 2000;67(5):352-6. Gotoh H, Masuzaki H, Yoshida A, Yoshimura S, Miyamura T, Ishimaru T. Predicting incomplete uterine rupture with vaginal sonography during the late second trimester in women with prior cesarean, Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(4):596-600. Mozurkewich EL, Hutton EK. Elective repeat cesarean delivery versus trial of labor: a meta-analysis of the literature from 1989 to 1999, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(5):1187-97. Vashevnik S, Walker S, Permezel M. Stillbirths and neonatal deaths in appropriate, small and large birthweight for gestational age fetuses, Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(4):302-6. Jones RO, Nagashima AW, Hartnett-Goodman MM, Goodlin RC. Rupture of low transverse cesarean scars during trial of labor, Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77(6):815-7. Scott JR. Mandatory trial of labor after cesarean delivery: an alternative viewpoint, Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77(6):811-4. Alexander JM, Leveno KJ, Hauth J, Landon MB, Thom E, Spong CY, et al. Fetal injury associated with cesarean delivery, Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):885-90. Towner D CM, Eby-Wilkens E, Gilbert WM. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury., N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1709-14. Hankins GD, Clark SM, Munn MB. Cesarean section on request at 39 weeks: impact on shoulder dystocia, fetal trauma, neonatal encephalopathy, and intrauterine fetal demise, Semin Perinatol. 2006;30(5):276-87. Morrison JJ, Rennie JM, Milton PJ. Neonatal respiratory morbidity and mode of delivery at term: influence of timing of elective caesarean section, Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102(2):101-6. ACOG Committee on Educational Bulletins. Assessment of fetal lung maturity, Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;230(56):191-8. Yee W AH, Wood S. Elective caesarean delivery, neonatal intensive care unit admission, and neonatal respiratory distress., Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;11:823-8. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Caesarean Section CG132. November 2011. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13620/57163/57163.pdf. Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Thom EA, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries, Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1226-32. Delaney T, Young DC. Spontaneous versus induced labor after a previous cesarean delivery, Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(1):39-44. Macones GA, Cahill A, Pare E, Stamilio DM, Ratcliffe S, Stevens E, et al. Obstetric outcomes in women with two prior cesarean deliveries: is vaginal birth after cesarean delivery a viable option?, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(4):1223-8; discussion 8-9. Horenstein JM, Phelan JP. Previous cesarean section: the risks and benefits of oxytocin usage in a trial of labor, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(5):564-9. Flamm BL, Goings JR, Fuelberth NJ, Fischermann E, Jones C, Hersh E. Oxytocin during labor after previous cesarean section: results of a multicenter study, Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70(5):709-12. Hoffman MK, Sciscione A, Srinivasana M, Shackelford DP, Ekbladh L. Uterine rupture in patients with a prior cesarean delivery: the impact of cervical ripening, Am J Perinatol. 2004;21(4):217-22. Tahseen S, Griffiths M. Vaginal birth after two caesarean sections (VBAC-2)-a systematic review with meta-analysis of success rate and adverse outcomes of VBAC-2 versus VBAC-1 and repeat (third) caesarean sections, BJOG. 2010;117(1):5-19. Varner MW, Leindecker S, Spong CY, Moawad AH, Hauth JC, Landon MB, et al. The MaternalFetal Medicine Unit cesarean registry: trial of labor with a twin gestation, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):135-40. Cahill A, Stamilio DM, Pare E, Peipert JP, Stevens EJ, Nelson DB, et al. Vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) attempt in twin pregnancies: is it safe?, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 Pt 2):1050-5. Miller DA, Mullin P, Hou D, Paul RH. Vaginal birth after cesarean section in twin gestation, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):194-8. Ford AA, Bateman BT, Simpson LL. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in twin gestations: a large, nationwide sample of deliveries, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(4):1138-42. Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 21 70. 71. 72. 73. Goyal V. Uterine rupture in second-trimester misoprostol-induced abortion after cesarean delivery: a systematic review, Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(5):1117-23. Kücükgöz Gülec U, Urunsak IF, Eser E, Guzel AB, Ozgunen FT, Evruke IC, et al. Misoprostol for midtrimester termination of pregnancy in women with 1 or more prior cesarean deliveries. 2003. Berghella V, Airoldi J, O'Neill AM, Einhorn K, Hoffman M. Misoprostol for second trimester pregnancy termination in women with prior caesarean: a systematic review, BJOG. 2009;116(9):1151-7. Dodd JM, Crowther CA. Misoprostol for induction of labour to terminate pregnancy in the second or third trimester for women with a fetal anomaly or after intrauterine fetal death, Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(4):CD004901. Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 22 Appendices Appendix A Maternal Morbidity of Women Who Had Caesarean Deliveries Without Labour 59 Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 23 Appendix B Outcomes of VBAC comparing patients with one previous caesarean section with those multiple previous caesarean sections. STUDY STRUCTURE (Numbers of patients undergoing planned VBAC) SUCCESS RATE FOR VBAC (%) RATE OF SCAR BREAKDOWN (%) (p value) (STATISTICS) SIGNIFICANT INCREASE IN MAJOR MATERNAL MORBIDITY REPORTED IF >1 CAESAREAN SECTION LANDON et.al (2006) Prospective (USA) 1 previous LUSCS (16,915) 74% 0.7% (p<0.001) (NS) 66% 0.9% 76% 0.72% (p<0.001) (p<0.001) 71% 1.59% 1 previous LUSCS (1,110) 71% 1.1% (p<0.05) (NS) ≥ 2 previous LUSCS (302) 64% 1.9% 1 previous LUSCS (3,757) 75% 0.8% (p=0.001) (p=0.001) 2 previous LUSCS (134) 62% 3.7% ≥ 2 previous LUSCS (648) TAHSEEN AND GRIFFITHS (2009) Literature Review (Case and Cohort Studies) 1 previous LUSCS (50,685) 2 previous LUSCS (4,564) ASA KURA AND MYERS (1995) CAUGHEY et.al (1999) Yes No Retrospective (USA) No Retrospective (USA) Yes Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 24 MACONES et.al Retrospective (USA) (2005) 1 previous LUSCS (12,535) 76% 0.9% (NS) (OR=2.0 95% CI 1.24 – 3.27) 2 previous LUSCS (1,082) 75% 1.8% Yes Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 25 Appendix C Women’s Health Committee Membership Name Associate Professor Stephen Robson Dr James Harvey Associate Professor Anusch Yazdani Associate Professor Ian Pettigrew Dr Ian Page Professor Yee Leung Professor Sue Walker Dr Lisa Hui Dr Joseph Sgroi Dr Marilyn Clarke Dr Donald Clark Associate Professor Janet Vaughan Dr Benjamin Bopp Associate Professor Kirsten Black Dr Jacqueline Boyle Dr Martin Byrne Ms Catherine Whitby Ms Sherryn Elworthy Dr Nicola Denton Position on Committee Chair and Board Member Deputy Chair and Councillor Member and Councillor Member and Councillor Member and Councillor Member of EAC Committee General Member General Member General Member General Member General Member General Member General Member General Member Chair of the ATSIWHC GPOAC representative Community representative Midwifery representative Trainee representative Appendix D Overview of the development and review process for this statement i. Steps in developing and updating this statement This statement was originally developed in July 2010 and was most recently reviewed in July 2015. The Women’s Health Committee carried out the following steps in reviewing this statement: ii. • Declarations of interest were sought from all members prior to reviewing this statement. • Structured clinical questions were developed and agreed upon. • An updated literature search to answer the clinical questions was undertaken. • At the July 2015 face-to-face committee meeting, the existing consensus-based recommendations were reviewed and updated (where appropriate) based on the available body of evidence and clinical expertise. Recommendations were graded as set out below in Appendix B part iii) Declaration of interest process and management Declaring interests is essential in order to prevent any potential conflict between the private interests of members, and their duties as part of the Women’s Health Committee. A declaration of interest form specific to guidelines and statements was developed by RANZCOG and approved by the RANZCOG Board in September 2012. The Women’s Health Committee members Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 26 were required to declare their relevant interests in writing on this form prior to participating in the review of this statement. Members were required to update their information as soon as they become aware of any changes to their interests and there was also a standing agenda item at each meeting where declarations of interest were called for and recorded as part of the meeting minutes. There were no significant real or perceived conflicts of interest that required management during the process of updating this statement. iii. Grading of recommendations Each recommendation in this College statement is given an overall grade as per the table below, based on the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendations for Developers of Guidelines. Where no robust evidence was available but there was sufficient consensus within the Women’s Health Committee, consensus-based recommendations were developed or existing ones updated and are identifiable as such. Consensus-based recommendations were agreed to by the entire committee. Good Practice Notes are highlighted throughout and provide practical guidance to facilitate implementation. These were also developed through consensus of the entire committee. Recommendation category Description Evidence-based A Body of evidence can be trusted to guide practice B Body of evidence can be trusted to guide practice in most situations C Body of evidence provides some support for recommendation(s) but care should be taken in its application D The body of evidence is weak and the recommendation must be applied with caution Consensus-based Recommendation based on clinical opinion and expertise as insufficient evidence available Good Practice Note Practical advice and information based on clinical opinion and expertise Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 27 Appendix E Full Disclaimer This information is intended to provide general advice to practitioners, and should not be relied on as a substitute for proper assessment with respect to the particular circumstances of each case and the needs of any patient. This information has been prepared having regard to general circumstances. It is the responsibility of each practitioner to have regard to the particular circumstances of each case. Clinical management should be responsive to the needs of the individual patient and the particular circumstances of each case. This information has been prepared having regard to the information available at the time of its preparation, and each practitioner should have regard to relevant information, research or material which may have been published or become available subsequently. Whilst the College endeavours to ensure that information is accurate and current at the time of preparation, it takes no responsibility for matters arising from changed circumstances or information or material that may have become subsequently available. Birth after previous caesarean section C-Obs 38 28