closing the implementation gap

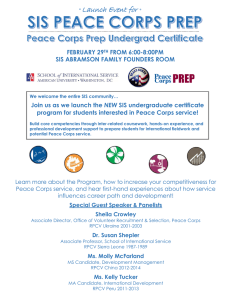

advertisement