COMM 755 (#25147) Seminar in Rhetoric and Public Address– Fall...

advertisement

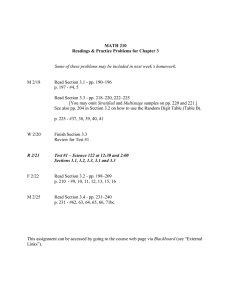

Course Title and Course Number COMM 755 (#25147) Seminar in Rhetoric and Public Address– Fall 2015 Course Information Class Days: Wednesdays Class Times: 7 p.m. to 9:40 p.m. Class Location: COMM 209 Instructor: Dr. Luke Winslow Course Overview Office Hours Times: MW 3:45 to 5 pm, and by appointment Office Hours Location: COMM 202 E-mail: lwinslow@mail.sdsu.edu Cell phone: (909) 472-1313 Welcome to Rhetoric and Public Address! Our course will explore how public address shapes democracy in the United States. I love this subject and I hope you will, as well. Public address is the most important mode of expression for people seeking to broaden the lines of power and privilege in American society. Public address is the most democratic mode of civic communication. And public address is the most efficient and effective way to change the world. You do not need to own a newspaper, a television channel, or a radio station to express your ideas through public speech. You do not need to have your name on a building. You do not need an elite education. All you need is your voice. Indeed, the contours of history are shaped by the indescribable power of the spoken word. More specifically, our course will explore the definitional parameters of rhetoric and public address as a scholarly discipline; we will examine the most promising and productive areas of public address research; and we will work hard to apply this scholarship in such a way that the rhetorical dimensions of your social, economic, and political worlds are illuminated more richly and vividly. Student learning objectives: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Identify the best rhetorical practices of great orators. This objective aligns with the School of Communication’s desire to graduate students with a working knowledge of the core concepts, definitions, and assumptions of the communication discipline. Demonstrate an awareness of how public address fosters more engaged citizenship and in turn, assist in developing both the skills and inspiration to “speak out” yourself. This objective aligns with the School of Communication’s desire to graduate students who can extemporaneously and proactively generate and competently present sound arguments in communicative performance contexts. Demonstrate an understanding of how public discourse shapes the American democratic experience – for good or ill. This objective aligns with the School of Communication’s desire to graduate students who can demonstrate an awareness of the role of communication in specific contexts. Analyze the ways in which public address has influenced our understanding of the discipline of communication studies. This objective aligns with the School of Communication’s desire to graduate students with an awareness of the history, nature, scope, and evolution of communication in our discipline. Analyze and evaluate the rhetorical strategies that influence the effectiveness of political messaging. This objective aligns with the School of Communication’s desire to graduate students who can diagnose the relevance and implications of communication and politics in hypothetical and actual contexts. Demonstrate and understanding of what is means to effectively deliberate, and then display the ability to train people on how to contribute to a more robust and productive democratic deliberation. This objective aligns with the School of Communication’s desire to gradate more competent “citizen” communicators who can contribute to improve public deliberation. Blackboard and e-mail: We will be utilizing the University Blackboard system extensively throughout the semester. If you are not already familiar with this system, I encourage you to peruse the Blackboard site. Log into the system with your Red ID and PIN at https://blackboard.sdsu.edu/webapps/login You will automatically be entered on the COMM 755 course. I will communicate with the class through Blackboard announcements and e-mail sent from the Blackboard site, so make sure you have your current e-mail address on file with the University. Also, you should be in the habit of checking your e-mail daily in order to insure that you do not miss any class messages. 1 Course Materials Required: The Handbook of Rhetorical and Public Address. Eds, Shawn J. Parry-Giles and J. Michael Hogan. 2010. Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA. Edwin Black. Rhetorical Criticism: A Study in Method (New York: Macmillan: 1965). Optional: [useful for our course and might be nice to have in your library but not required] Stephen E. Lucas and Martin J. Medhurst. “Words of a Century: The Top 100 American Speeches, 19001999. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. Ronald F. Reid and James F. Klumpp, American Rhetorical Discourse 3rd ed., (Long Grove, IL: Waveland, 2005). James Jasinski, Sourcebook on Rhetoric: Key Concepts in Contemporary Rhetorical Studies (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2001). Other course materials will be made available on Blackboard. Course Structure and Conduct As a graduate seminar, our class will function primarily as a focused and collaborative discussion. And because this is a discussion-intensive course, I ask you to keep up with assigned readings and come to class prepared to talk about them. The success of this course depends upon your active participation. I will provide introductory overview of our course material, especially early in the semester, to help frame our discussions, but I hope that we can spend most of our time actively talking together about what we will read and see in our course and in our world. Course Assessment and Grading Required assignments: 1. Reading responses: For ten of our class sessions, you will complete a Reading Response in which you read the Primary Readings for the week and describe in a Word document the research question, paradox, and thesis of each reading. You will also include a short response the prompts I pose and list any lingering questions you have about the subject or the readings. You will type up your responses and submit them to turnitin.com by 12 noon on the day of class. I will use these responses to guide our discussion for that day’s subject. There will 11 Reading Response sessions, but you only have to complete 10. 2. Discussion lead: You will choose a topic or a set of readings for one of our class sessions that is of interest to you. Working with a classmate, you will be responsible for teaching the Secondary Readings to the class. Assume the readings are important and we may need to know them for our term papers, future research projects, or our own classes in the future. Include a handout that summarizing each reading. Be a discussion leader: practice the best pedagogical principles you have learned. 3. Term paper: You will conduct a rhetorical analysis of a public address synthesizing and integrating the best practices discussed in our lectures, discussions, and readings. Your final draft should be NCA conventionquality. To assist with this, your term paper will be constructed in stages, with ample time for feedback from your classmates and me. You will submit (and receive feedback) on a Research Proposal, a Literature Review, and a Final Draft at the end of the semester. The last class day will be an opportunity for you to present your analysis to the class. 4. Participation: Participation will be based on a number of important factors including critical engagement with course material, willingness to discuss material, and ability to further discussion by prompting insightful questions. There is no partisan or party line to follow in this course, and no student will ever be 2 penalized for respectfully disagreeing with the course material or class discussion. We will likely be discussing issues about which people feel strongly. Vigorous, yet collegial, debate is encouraged. Know in advance that all ideas are equally subject to debate, including my own. You will not be graded on your level of agreement with my opinions, but on your ability to make an argument and defend it soundly. The following assignments will comprise your grade in the class: Readings responses (10 at 20 points each) 200 points Discussion lead 100 points Research Proposal 100 points Literature Review 200 points Term paper presentation 50 points Term paper final draft 300 points Participation 50 points Total: /1000 points The following scale will be used to determine final course grades: A AB+ B BC+ C CD+ D DF 93% and above - 930 – 1000 90-92.9% - 900 – 929 87-89.9% - 870 - 899 83-86.9% - 830 - 869 80-82.9% - 800 - 829 77-79.9% – 770 - 799 73-76.9% - 730 - 769 70-72.9% - 700 - 729 67-69.9% - 670 - 699 63-66.9% - 630 - 669 60-62.9% - 600 - 629 59.9% and below – 599 - 0 A curve is not used in this course. Other Course Policies If you have questions about your grade on an assignment, please see me within 5 business days of receiving the grade (day 1 is the day the assignment is returned). After 5 days, a graded assignment is not eligible for review. Graded assignments submitted for review may be re-graded in their entirety. If you have questions about a grade or any other aspect of the course, please see me after class or during office hours. If your schedule conflicts with my office hours, I will be glad to schedule additional office time to meet with you. No assignment will be accepted after its due date if you do not talk with me beforehand. If you miss a handout or lose a handout or the syllabus, contact a classmate or go to our Blackboard course site. You are responsible for all materials on the day they are handed out. Your participation grade is not assumed. It must be earned. This syllabus does not bind the instructor to specific details; the instructor reserves the right to adjust the course design. The School of Communication website can be found at http://communication.sdsu.edu/ We will be using APA format for citation. See the Purdue Owl website for assistance: http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/section/2/10/ Also see this APA tutorial for assistance: http://flash1r.apa.org/apastyle/basics/index.htm 3 Syllabus statement for students with disabilities: If you are a student with a disability and believe you will need accommodations for this class, it is your responsibility to contact Student Disability Services at (619) 594-6473. To avoid any delay in the receipt of your accommodations, you should contact Student Disability Services as soon as possible. Please note that accommodations are not retroactive, and that accommodations based upon disability cannot be provided until you have presented your instructor with an accommodation letter from Student Disability Services. Your cooperation is appreciated. Academic dishonesty policy of the School of Communication Plagiarism is theft of intellectual property. It is one of the highest forms of academic offense because in academe, it is a scholar’s words, ideas, and creative products that are the primary measures of identity and achievement. Whether by ignorance, accident, or intent, theft is still theft, and misrepresentation is still misrepresentation. Therefore, the offense is still serious, and is treated as such. In any case in which a Professor or Instructor identifies evidence for charging a student with violation of academic conduct standards or plagiarism, the presumption will be with that instructor’s determination. However, the faculty/instructor(s) will confer with the director to substantiate the evidence. Once confirmed, the evidence will be reviewed with the student. If, following the review with the student, the faculty member and director determine that academic dishonesty has occurred, the evidence will be submitted to the Office of Student Rights and Responsibilities. The report “identifies the student who was found responsible, the general nature of the offense, the action taken, and a recommendation as to whether or not additional action should be considered by the campus judicial affairs office .” (CSSR Website[1]). [1] http://www.sa.sdsu.edu/srr/academics1.html Intellectual Property: The syllabus, lectures and lecture outlines are personal copyrighted intellectual property of the instructor, which means that any organized recording for anything other than personal use, duplication, distribution, or profit is a violation of copyright and fair use laws. Proper Source Attribution: Proper attribution occurs by specifying the source of content or ideas. This is done by (a) providing quotation marks around text, when directly quoted, and (b) clearly designating the source of the text or information relied upon in an assignment. Text that is identical with another source but without quotation marks constitutes plagiarism, regardless of whether you included the original source. Specific exemplary infractions and consequences: a. Reproducing a whole paper, paragraph, or large portions of unattributed materials (whether represented by: (i) multiple sentences, images, or portions of images; or (ii) by percentage of assignment length) without proper attribution, will result in assignment of an “F” in the course, and a report to Student Rights and Responsibilities. b. Reproducing a sentence or sentence fragment with no quotation marks but source citation, or subsets of visual images without source attribution, will minimally result in an “F” on the assignment. Repeated or serious cases will result in assignment of an “F” in the course, and a report to Student Rights and Responsibilities. Self-plagiarism: Students often practice some form of ‘double-dipping,’ in which they write on a given topic across more than one course assignment. In general, there is nothing wrong with double-dipping topics or sources, but there is a problem with double-dipping exact and redundant text. It is common for scholars to write on the same topic across many publication outlets; this is part of developing expertise and the reputation of being a scholar on a topic. Scholars, however, are not permitted to repeat exact text across papers or publications except when noted and attributed, as this wastes precious intellectual space with repetition and does a disservice to the particular source of original presentation by ‘diluting’ the value of the original presentation. Any time that a writer simply ‘cuts-andpastes’ exact text from former papers into a new paper without proper attribution, it is a form of self-plagiarism. Consequently, a given paper should never be turned in to multiple classes. Entire paragraphs, or even sentences, should not be repeated word-for-word across course assignments. Each new writing assignment is precisely that, a new writing assignment, requiring new composition on the student’s part. Secondary citations: Secondary citation is not strictly a form of plagiarism, but in blatant forms, it can present similar ethical challenges. A secondary citation is citing source A, which in turn cites source B, but it is source B’s ideas or content that provide the basis for the claims the student intends to make in the assignment. For example, assume that there is an article by Jones (2006) in the student’s hands, in which there is a discussion or quotation of 4 an article by Smith (1998). Assume further that what Smith seems to be saying is very important to the student’s analysis. In such a situation, the student should always try to locate the original Smith source. In general, if an idea is important enough to discuss in an assignment, it is important enough to locate and cite the original source for that idea. There are several reasons for these policies: (a) Authors sometimes commit citation errors, which might be replicated without knowing it; (b) Authors sometimes make interpretation errors, which might be ignorantly reinforced (c) Therefore, reliability of scholarly activity is made more difficult to assure and enforce; (d) By relying on only a few sources of review, the learning process is short-circuited, and the student’s own research competencies are diminished, which are integral to any liberal education; © By masking the actual sources of ideas, readers must second guess which sources come from which citations, making the readers’ own research more difficult; (f) By masking the origin of the information, the actual source of ideas is misrepresented. Some suggestions that assist with this principle: When the ideas Jones discusses are clearly attributed to, or unique to, Smith, then find the Smith source and citation. When the ideas Jones is discussing are historically associated more with Smith than with Jones, then find the Smith source and citation. In contrast, Jones is sometimes merely using Smith to back up what Jones is saying and believes, and is independently qualified to claim, whether or not Smith would have also said it; in such a case, citing Jones is sufficient. Never simply copy a series of citations at the end of a statement by Jones, and reproduce the reference list without actually going to look up what those references report—the only guarantee that claims are valid is for a student to read the original sources of those claims. Solicitation for ghost writing: Any student who solicits any third party to write any portion of an assignment for this class (whether for pay or not) violates the standards of academic honesty in this course. The penalty for solicitation (regardless of whether it can be demonstrated the individual solicited wrote any sections of the assignment) is F in the course. TurnItIn.com The papers in this course may be submitted electronically in Word (preferably .docx) on the due dates assigned, and will require verification of submission to Turnitin.com. “Students agree that by taking this course all required papers may be subject to submission for textual similarity review to TurnItIn.com for the detection of plagiarism. All submitted papers will be included as source documents in the TurnItIn.com reference database solely for the purpose of detecting plagiarism of such papers. You may submit your papers in such a way that no identifying information about you is included. Another option is that you may request, in writing, that your papers not be submitted to TurnItIn.com. However, if you choose this option you will be required to provide documentation to substantiate that the papers are your original work and do not include any plagiarized material” (source: language suggested by the CSU General Counsel and approved by the Center for Student’s Rights and Responsibilities at SDSU) Specific exemplary infractions and consequences: Course failure: Reproducing a whole paper, paragraph, or large portions of unattributed materials without proper attribution, whether represented by: (a) multiple sentences, images, or portions of images; or (b) by percentage of assignment length, or solicitation of a ghost writer, will result in assignment of an “F” in the course in which the infraction occurred, and a report to the Center for Student Rights and Responsibilities (CSRR2). Assignment failure: Reproducing a sentence or sentence fragment with no quotation marks, but with source citation, or subsets of visual images without source attribution, will minimally result in an “F” on the assignment, and may result in greater penalty, including a report to the CSRR, depending factors noted below. In this instance, an “F” may mean anything between a zero (0) and 50%, depending on the extent of infraction. Exacerbating conditions—Amount: Evidence of infraction, even if fragmentary, is increased with a greater: (a) number of infractions; (b) distribution of infractions across an assignment; or (c) proportion of the assignment consisting of infractions. Exacerbating conditions—Intent: Evidence of foreknowledge and intent to deceive magnifies the seriousness of the offense and the grounds for official response. Plagiarism, whether ‘by accident’ or ‘by 5 ignorance,’ still qualifies as plagiarism—it is all students’ responsibility to make sure their assignments are not committing the offense. Exceptions: Any exceptions to these policies will be considered on a case-by-case basis, and only under exceptional circumstances. HOWEVER, THERE ARE NO EXCUSES ALLOWED BASED ON IGNORANCE OF WHAT CONSTITUTES PLAGIARISM, OR OF WHAT THIS POLICY IS. Tentative Daily Schedule Although every effort will be made to follow the proposed schedule as closely as possible, the instructor reserves the right to make changes in the order in which certain topics are presented. I will do my best to inform students of schedule changes as far in advance as possible. 1. Week 1 – August 26 – Course introduction: Who gets to speak? Who cares? 2. Week 2 – September 2 – Defining our key terms; overview of public address a. Primary readings (Reading Response due) i. “Introduction: The Study of Rhetoric and Public Address” in Parry-Giles and Hogan ii. Martin Medhurst, “The History of Public Address as an Academic Study” in Parry-Giles and Hogan. b. Secondary readings i. Martin Medhurst, “Looking Back on Our Scholarship: Some Paths Now Abandoned,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 101:1 (2015): 186-196. ii. Barry Brummett, “Rhetorical Theory as Heuristic and Moral: A Pedagogical Justification,” Communication Education 33 (1984) iii. Barry Brummett, “Introduction,” Reading Rhetorical Theory 3. Week 3 – September 9 – Historical and contemporary approaches to public address scholarship a. Primary readings (Reading Response due) i. Edwin Black, Rhetorical Criticism: A Study in Method (New York: Macmillan: 1965). b. Secondary readings i. Andrew King, “Scholarship yesterday, Today and Tomorrow,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 101:1 (2015). ii. Raymie E. McKerrow “Research in Rhetoric” Revisited,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 101:1 (2015). iii. Maurice Charland, 1987). Constitutive Rhetoric: The Case Of The Peuple Quebecois, Quarterly Journal Of Speech, 73(2), 133-150. 4. Week 4 – September 16 – Mechanisms of public address scholarship a. Primary readings (Reading Response due) i. “Introduction” in Reid and Klumpp’s American Rhetorical Discourse ii. Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, “Rhetorical Criticism 2009: A Study in Method” In Parry-Giles and Hogan b. Secondary readings i. Hart, R. P. (1986). Contemporary Scholarship in Public Address: A Research Editorial. Western Journal Of Speech Communication 50(3), 283-295. ii. Rowland, R. C., & Jones, J. M. (2007). Recasting the American Dream and American Politics: Barack Obama's Keynote Address to the 2004 Democratic National Convention. Quarterly Journal Of Speech, 93(4), 425-448. 5. Week 5 – September 23 – Myth, value, and narrative in public address scholarship a. Primary readings (Reading Response due) i. Luke Winslow, “Comforting the Comfortable: Extreme Makeover Home Edition’s Ideological Conquest,” Critical Studies in Media Communication (2010). 6 Roderick P. Hart, “The Functions of Human Communication in the Maintenance of Public Values," In Carroll C. Arnold and John Waite Bowers, The Handbook of Rhetorical and Communication Theory (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1984), 749-791. (Blackboard) Secondary readings i. Hart, R. P. (1978). An Unquiet Desperation: Rhetorical Aspects Of 'Popular' Atheism In The United States. Quarterly Journal Of Speech, 64(1), 33-46. ii. Walter R. Fisher, Reaffirmation and Subversion of the American Dream, Quarterly Journal of Speech 59:2 (1973): 160-167. iii. Luke Winslow, “American Dream” chapter in Economic Injustice (on Blackboard) ii. b. 6. Week 6 – September 30 - Image and aesthetics in public address scholarship a. Guest lecture: Marquesa Cook-Whearty, SDSU MA graduate, ‘15 b. Primary readings (Reading Response due) i. Cara A. Finnegan, “Studying Visual Modes of Public Address: Lewis Hine’s ProgressiveEra Child Labor Rhetoric,” In Parry Giles and Hogan. ii. Marquesa Cook-Whearty, Luke Winslow, and Patricia Geist-Martin, The Last Meal Campaign: A Visual Exploration of Innocence and the Death Penalty, NCA paper (Blackboard) c. Secondary readings i. Cloud, D. L. (2004). To veil the threat of terror: Afghan women and the <clash of civilizations> in the imagery of the U.S. war on terrorism. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 90(3), 285-306. ii. Dickinson, G., Ott, B. & Aoki, E. (2005). Memory and myth at the Buffalo Bill museum. Western Journal of Communication 69, 2, 85-108. iii. Ivie, R. L. (1980). Images of savagery in American justifications for war. Communication Monographs 47, p. 279-294. iv. Winslow, Luke A. 2014. "The Imaged Other: Style and Substance in the Rhetoric of Joel Osteen." Southern Communication Journal 79, no. 3: 250-271. 7. Week 7 – October 7 – The American Presidency and public address scholarship a. Primary readings (Reading Response due) i. John Murphy, “Theory and Public Address: The Allusive Mr. Bush,” in Parry-Giles and Hogan. ii. Mary E. Stuckey, “Jimmy Carter, Human Rights, and Instrumental Effects of Presidential Rhetoric, in Parry-Giles and Hogan. b. Secondary readings i. Campbell and Jamieson, Presidents Creating the Presidency: Deeds Done in Words, “Introduction” ii. Roderick P. Hart, “Introduction” and “Chapter one: Speech and Effort” in The Sound of Leadership (Blackboard) iii. Medhurst, M. J. (2009). Evangelical Christian Faith and Political Action: Mike Huckabee and the 2008 Republican Presidential Nomination. Journal of Communication & Religion, 32(2), 199-23 8. Week 8 – October 14 – American religion and public address scholarship a. Research Proposal due b. Guest lecture: Dr. Paul Minifee on Rev. Jermain Loguen's speech against the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 c. Primary readings (Reading Response due) i. Read Rev. Jermain W. Loguen’s speech on the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850 (Blackboard) ii. Paul Minifee. (2013). “Rhetoric of Doom and Redemption: Reverend Jermain Loguen's Jeremiadic Speech Against the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850,” Advances in the History of Rhetoric, 16:1, 29-57. d. Secondary readings i. Minifee, P. A. (2011). Converting Slaves to Citizens: Prophetic Ethos in Sermons of Bishop James W. Hood. Journal Of Communication & Religion, 34(2), 105-127. 7 ii. iii. 9. Hart, R. P. (1971). The Rhetoric Of The True Believer. Speech Monographs, 38(4), 249261. Jackson, B. (2010). The Prophetic Alchemy of Jim Wallis. Rhetoric Review, 29(1), 48-68. Week 9 – October 21 – Race and public address scholarship a. Primary readings (Reading Response due) i. Eric King Watts, “The Problem of Race in Public Address Research: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Conflicted Aesthetics of Race,” In Parry-Giles and Hogan ii. Rowland, R. C., & Jones, J. M. (2011). One Dream: Barack Obama, Race, And The American Dream. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 14(1), 125-154. b. Secondary readings i. Gunn, J., & McPhail, M. L. (2015). Coming Home to Roost: Jeremiah Wright, Barack Obama, and the (Re)Signing of (Post) Racial Rhetoric. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 45(1), 1-24. ii. McCann, B. J. (2014). On Whose Ground? Racialized Violence and the Prerogative of “Self-Defense” in the Trayvon Martin Case. Western Journal Of Communication, 78(4), 480-499. 10. Week 10 – October 28 – Gender and public address scholarship a. Primary readings (Reading Response due) i. Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, “Introduction” from Man Cannot Speak For Her (Blackboard) ii. Campbell, K. K. (1998). The Discursive Performance Of Femininity: Hating Hillary. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 1(1), 1-19. iii. Bonnie J. Dow, “Feminism and Public Address Research: Television News and the Constitution of Women’s Liberation,” in Parry-Giles and Hogan b. Secondary readings i. Cheryl R. Jorgenson-Earp, “Lilies and Lavatory Paper,” in Parry-Giles and Hogan ii. Dow, B. J., & Tonn, M. B. (1993). `Feminine style and political judgment in the rhetoric of Ann Richards. Quarterly Journal Of Speech, 79(3), 286. iii. Pezzullo, P. C. (2003). Resisting "National Breast Cancer Awareness Month": The Rhetoric of Counterpublics and their Cultural Performances. Quarterly Journal Of Speech, 89(4), 345-365 11. Week 11 – November 4 – Class, poverty and public address scholarship a. Primary readings (Reading Response due) i. Luke Winslow, “Introduction” Economic Injustice (Blackboard) ii. Asen, R. (2001). Nixon's Welfare Reform: Enacting Historical Contradictions Of Poverty Discourses. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 4(2), 261-279. b. Secondary readings i. Asen, R. (2010). Reflections On The Role Of Rhetoric In Public Policy. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 13(1), 121-143. ii. Asen, R. (2003). Women, Work, Welfare: A Rhetorical History Of Images Of Poor Women In Welfare Policy Debates. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 6(2), 285-312. iii. D. Zarefsky, "President Johnson's War on Poverty: The Rhetoric of Three 'Establishment' Movements," Communication Monographs 44 (1977): 352-373. 12. Week 12 – November 11 – Veterans Day (Campus closed) Literature Review due: ______________________ 13. Week 13 – November 18 – National Communication Association annual convention 14. Week 14 – November 25 – Thanksgiving holiday 15. Week 15 – December 2 a. Social justice and public address scholarship b. Primary readings (Reading Response due) 8 i. c. Richard Gregg: "The Ego Function of the Rhetoric of Protest," Philosophy and Rhetoric 4 (1971): 71-91. ii. Rushing, J. H., & Frentz, T. S. (1991). Integrating ideology and archetype in rhetorical criticism. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 77(4), 385400. Secondary readings i. Howard Zinn chapter “The Coming Revolt of the Guards” chapter (Blackboard) ii. Hartnett, S. J., Wood, J. K., & McCann, B. J. (2011). Turning Silence into Speech and Action: Prison Activism and the Pedagogy of Empowered Citizenship. Communication & Critical/Cultural Studies, 8(4), 331-352. iii. Hartnett, S. J. (2010). Communication, Social Justice, and Joyful Commitment. Western Journal Of Communication, 74(1), 68-93. 16. Week 16 – December 9 a. Paper presentations Term paper final draft due: __________________________________________ 9