Introduction (setting the scene).

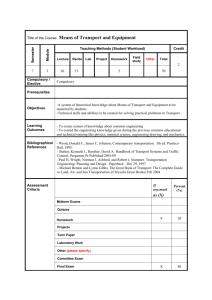

advertisement

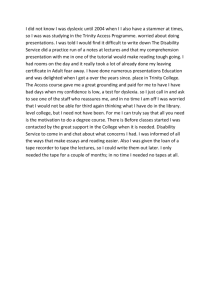

Introduction (setting the scene). I was born in 1937, two months ahead of schedule. My mother was 44 and my father was 50. The Jessie McPherson Hospital nursed me through from my premature birth, with none of today's modern medical equipment. My Mum and Dad lived in Newmarket, a Melbourne suburb, with my Mother's Mum - my only living Grandmother. At the time of my birth my Grandmother was almost bedridden due to angina; my mother's single sister (my Auntie Em) also lived in the house. In the tradition of my family, I commenced Sunday School at the Newmarket Baptist Sunday School at the age of 4. My father was a soldier in World War I. He had lost an eye in the war and was the Victorian Treasurer of the Partially Blinded Soldiers Association. On some occasions he stuttered over one word in a conversation; it was hardly noticeable. He died when I was 10, as a result of war injuries. I had a sheltered upbringing with lots of uncles and aunties who visited regularly, as my mother had two married brothers and one married sister, and they between them had nine offspring, the eldest of whom was over 30 and married at the time of my birth. They all visited our home regularly. My father had two married brothers, and a married sister who at the time of my birth had provided me with six cousins. They also visited us, though not as regularly as those who came to see their grandmother. At the age of six, I commenced school at the Bank Street State School, in Ascot Vale. As far as I can remember, I began to stammer when I was in Grade 3. I would go through school until 1949, at Moonee Ponds Central School in 1950 and 1951, and at Wesley College in Prahran from 1952 to the end of 1955 without ever answering a question in a classroom with one notable exception. I was never in a school play. If I met a fellow student in the street and they said "Hullo", I was unable to reply. Throughout that time I never spoke to a stranger, nor could I speak on the telephone. I could speak to some very close friends and family members face to face (but not on the telephone). People thought I stammered because I was shy. They were wrong. I was shy because I stammered. I would try to speak to people, and to answer questions in the classroom. When I opened my mouth to speak, no sound emerged. To give you a better picture, let me recount some embarrassing and difficult happenings from my life which illustrate what I did and how I felt. Stories from Life Example A Following the death of my father I became a member of Junior Legacy. I remember all the boys from my Legacy Club were invited to a Gala Film Festival in the city when I was 12. I was booked to attend. When I arrived at the theatre, an official asked my surname. I was unable to say "Dickinson". He would not allow me to enter. I was disappointed and angry. Someone else told the man my name, and I was let in. It was humiliating. Example B When I was in Form IV (year 10) at Wesley College, my English teacher had all the boys in my class read a paragraph from one of the works of literature we were studying. Each boy in turn would stand and read a paragraph to the class. When my turn came to read, the paragraph began with the sentence: "Noiselessly, she went a step or two nearer". I stood. I tried to say the words - without success. The following conversation ensued: Teacher: "What is the first word, Boy?" Me: "Noiselessly, Sir." Teacher: "Good. Say it again and continue with the sentence." Me: "Noiselessly, ……." (a long silence) Teacher: "What is the second word, Boy?" Me: "She, Sir." Teacher: "Say: 'Noiselessly, she' and continue with the sentence." Me: "Yes Sir, Noiselessly, she ……….. (another long silence.) If the teacher's patience lasted, this pattern would continue until I was able to say four or five words in a row. Then he would give up and say - with great frustration: "Sit Down. You silly little boy!" The following week in that English class the procedure would be repeated with a different book. My classmates would sit patiently through it: I hated it. I hated not being able to speak. Example C As a teenager, and by then active in my local Baptist Church, all teenagers who were members of the Church, were required to present an oral confession of their faith at youth club meetings. I couldn't do it. So I commenced singing lessons. I was then able to find a Gospel Song, the words of which expressed my own beliefs. I would write its title on a sheet of paper, and add a request for the chairman of the meeting to announce my song and say it summed up my confession of faith. Some chairmen would try to kid me into announcing my solo. It didn't work. I was embarrassed in front of my peers. Example D. I started work in the Commonwealth Public Service Board, in Melbourne, in December 1955. I scheduled the appeals against people who were promoted throughout all Commonwealth Public Service Departments in Victoria. When appeals closed at 3 p.m. on a Friday each week, I would receive up to fifty telephone calls from people seeking advice concerning appeals. I would lift the receiver, but couldn't speak. The clerk sitting beside me, would take the receiver from me and say, "Ed Dickinson's phone, Marsh speaking." The callers would give him their name; he would tell me who it was and then say, "I'll put Mr. Dickinson on." Then he would hand me the receiver. And I would say, "Ed Dickinson speaking." I would then complete the telephone conversation without a worry. Looking back, I find this strange. It was not until I lost my stammer, years later, that I could answer the phone. Example E. In that same office I had my own stenographer to whom I was expected to dictate official letters. My stammer made dictation impossible. I would write out the letters by hand and give them to her with a note on the first page, which stated how many copies of each letter I wanted. I would just drop my draft on her desk without conversing. Example F. People often told me to sing my answers to questions. They told me, "People don't stutter when they sing." I tried that but - mostly - it didn't work for me, and if I did manage to sing my sentence, I felt very silly. In my mid twenties I was a tenor soloist in an 80-voice choir. I remember being given a solo in an oratorio in a large city auditorium. On the night of the concert when the time came for my solo the conductor with his back to the audience, pointed his baton at the organist. The organist played the opening chord of my solo: I opened my mouth, but no sound came out. Silence. The conductor flicked his baton a second time, the organist played the chord . . . . . silence. For the third time the conductor pointed to the organist; he played the chord and the conductor - a bass baritone, began my tenor solo. After the first few words, I joined him and he, hearing me singing, stopped singing. I continued through without further problems. Fortunately, as he had his back to the audience the audience was unaware what had happened. People who helped (or tried to). Many people did their best to help me. In Grade 5 my headmaster took an interest in me and spoke with Speech Professionals in the Education Department. I was sent to a Special School in Travencore for speech therapy. My Speech Therapist was a Miss Winter. She taught me how to breathe correctly and how to relax. When I visited her each week I would lie on a flat surface, and relax each set of muscles in my body, starting with my toes, and finishing with my neck and head. She would then lift my limbs in turn to check that I was fully relaxed. I remember that she talked to me throughout the process but I cannot remember exactly what she said. On the same weekly visits I sat with a Dr. Cathcart who was, I believe, a psychiatrist. We would chat for half an hour. It was hard at the first, but as I came to know him, my speech improved. After 6 months of weekly visits, which I enjoyed, he surprised me by telling me that I did not have a stammer. He said I need not see him any more. He also said that when I was older I would understand why I had a speech impediment and it would then stop. I also stopped seeing Miss Winter. I was puzzled, but not cured. Similar therapy was given to me when I was at Moonee Ponds Central, but it seemed to me that my stammer became worse each time I went to a therapist. Midway through year 12 at Wesley College, the Vocational Guidance Master interviewed me about my achievements in all aspects of my life and concluded by saying that I was an average student, average at sport, and not famous or infamous in anything at school. Yet, he said every boy in the school knew me because I was the boy with a stammer. He told me to find some other way to attract attention to myself. At the time I was hurt, but I had a sneaking suspicion that he was re-iterating what Dr Cathcart had said. An episode of my life was recently printed in a Wesley publication. It read: In Year 12 Ed was in the Headmaster's class for Divinity. He says he remembers the Head making a statement about God, which Ed believed to be wrong. He raised his hand, was asked to speak, and did. He told Frederick he was wrong, explained why, and sat down. Frederick smiled. The boys clapped furiously. At a recent address at Chum Creek Ed said, "In my naivety, I thought my classmates were clapping because I had argued with the Headmaster. I now know they were clapping me for speaking. But I also think that Frederick, knowing me to have been brought up in a strict Baptist Home, baited me. However, the stammer stayed. But Frederick left me knowing that I could speak in class if I really wanted to." During my time at Wesley the school prefects read the Bible Lesson at the morning School Assembly. They were coached by a voice expert. Long after leaving school I met him, and he discovered I still had my stammer, and that I had never had a date with a girl because I was unable to either ask girls out or speak to them. He wrote down the name of an English woman, Margaret Eldridge who had come to Australia to work as a speech therapist. He said she was very good at what she did and he believed she could help me. He went on to say she had worked in England with Lionel Logue who was the therapist to King George VI. My local doctor gave me a referral to see Mrs. Eldridge. I knew very little about her then, but I would learn much later that she had founded the 'The College of Therapists' in London in the 1930's and that Lionel Logue had been a Founding Member. I began seeing her once a week. She was a much older person than the therapists I had attended when a schoolboy. Mrs. Eldridge was probably in her fifties. She was almost a "mother figure" to me. It was the same as before; she had me doing all the same relaxation exercises I had done with other therapists. I wondered what was the point of it all. But one thing stands out in my mind. I told her one day about some of the suggestions learned people and friends, and even therapists, had suggested to rid me of my stammer. She told me they wouldn't work for me. She told me I was different from other people who had a stammer. She told me that there were no two stammerers or stutterers that were the same in the whole world. I found this incredulous and told her that I did not believe her. She replied by saying, "Would you believe me if I said that there were not two identical personalities in the whole world?" I said I could accept that. She said then, that I was different from everyone else in the world, and that my stammer was different from any other stammerer in the world. I accepted that from her. Two weeks after I had accepted her advice that I was different from other people who stammered and my particular stammer was unique, I was in a public meeting and the Chairman asked me a question. I knew the answer, I stood up, and without much thought answered in a strong, clear voice. My colleagues were amazed. So was I! My stammer had gone. 50 years later, I remember that evening quite well. My Own Thoughts on my Stammer. In Grade 3, I had a mate who lived on my street who had a stutter. He repeated the hard consonants at the start of each word. L-L-L-L-L- Like th-th-th-th-th-this. Everybody made a fuss of him. Surrounded by a large family, and being well behaved, no people outside my family took any notice of me. I was just an average kid; not naughty, not better than anyone. Somehow, psychologically, I think I copied my mate. I always hated my impediment. I dearly wanted to be rid of it. I really thought I did. The only letter I could sound without stammering was "S". I never went into a shop without a note, and I always handed the note to the person behind the counter. Unless all I wanted was 'half a dozen eggs'. I couldn't say 'half' but I could say 'six'. It seems that Dr. Cathcart (who would later become the Head of the Mental Health Department in Victoria), and my Vocational Master at Wesley were right in their diagnosis. But I wasn't ready to hear it. All that I am aware of, what Margaret Eldridge did that was different, was convince me I was a unique person. I don't know how that changed the subconscious desire to stammer - to one of not stammering. Perhaps she had a special aura of confidence which I caught. History tells us that Lionel Logue wrote no books and did not teach other therapists. Perhaps he, too, had an aura which he passed on. There are many references to 'Margaret Eldridge, Speech Therapist', on the web. As for me, I now enjoy public speaking and do it professionally. My advertising leaflets include: Ed Dickinson, The Speaker of Renown, was accredited as a Professional Speaker by the National Speakers Association of Australia, and is a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Training & Development, a Paul Harris Fellow of Rotary International, the author of two books, and a professional M.C. He has produced an audio CD and tape on speaking skills, is a Freeman of Australian Rostrum (Vic.) Inc., a member of WellSpring, the Ashburton Baptist Church, the RACV Club, the National Trust, and an associate member of the Graduate Union of Melbourne University. Conclusion Today, when I coach people in public speaking and watch them nervously approach the dais for the first time, it's not unusual to hear them say, "It's easy for you. You're a professional speaker. You don't know what it's like to face an audience and not be able to say a word." I smile, and sometimes share of little of my unique story with them. Each and every one are also unique. And I tell them so.