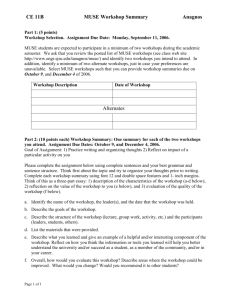

Faculty Perspectives 1

advertisement