General Education Annual Course Assessment Form Hist 153:

advertisement

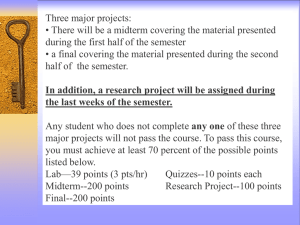

General Education Annual Course Assessment Form Course Number/Title: Hist 153: History of Women in Europe GE Area V Results reported for AY 2011-2012 (Pickering) # of sections: 2 # of instructors: 1 Course Coordinator: Mary Pickering E-mail: Mary.Pickering@sjsu.edu Department Chair: Patricia Evridge Hill College: Social Sciences Part 1 (1) What SLO(s) were assessed for the course during the AY? SLO 3: Students shall be able to explain how a culture outside the U.S. has changed in response to internal and external pressures. (2) What were the results of the assessment of this course? What were the lessons learned from the assessment? This course explores the economic, social, cultural, intellectual, and politics forces that have brought about change in European countries since antiquity. The countries that I cover in depth are Greece, Italy, France, England, Germany, and Russia. These are six countries outside of the United States. We focus a great deal on violent political forces, such as revolutions (i.e. the French Revolution), civil wars (the Parisian Commune of 1870), and wars (especially World War I and World War II to show how women participate in such events but their issues get conveniently pushed aside at the same time. Indeed, they are often blamed for the tragedies (French Revolution and Commune) and are told to go back to their homes and relinquish their newly obtained jobs or positions to men in order for society to “get back to normal.” This search for normalcy was particularly evident during the world wars of the twentieth century. Some of these political forces are “outside” because they involve wars between countries. But some political forces are internal. The development of democracy is one example. The growth of liberalism and then democracy in Britain, for example, inspired women to demand their rights as they saw their fathers, husbands, brothers, and sons obtain the right to vote. But political forces are not all that change societies. Economic and social changes play a big role as well. Industrialization is both an internal and external force. It relies on the development of industry within a country and commerce between countries. It affected women’s lives in a myriad of ways by diminishing their role as non-wage earners in the family, isolating them in their private spheres, depriving them of the better jobs, those that involved machines. On the other hand, it gave them more job opportunities Another source of change that we consider is consumerism. It both reinforced men’s tendency to objectify women but gave women agency in making their own way in business (Helena Rubenstein, Vivien Westwood). After all, one of the founders of the department store was a woman. A social change that is an “outside force” is immigration. The recent influx of Moslem immigrants to Europe has challenged European identity in a variety of ways and affected the status of Moslem women, who often seek freedom from their families by marrying Europeans. 1 As an intellectual historian, I also like to get students to think about cultural and intellectual forces. For example, women’s roles were debated intellectually among Bluestockings in the nineteenth century, Owenites (utopian socialists) in the nineteenth century, and second-wave feminists in the twentieth century. These represent internal forces for change. The Establishment was criticized from within. Religion is another internal force for change, although it is usually seen as something conservative. Protestant women, particularly the Quakers, pressed for changed in women’s position in the Church. That is why Quakers were so vocal in the abolition movement. Reactions against religion can be a force for change. I have students read several books on Islam in Europe to understand how the quarrel over the veil in public spaces has been a controversial internal force for change. As suggested above, both the European sense of identity and the place of Islamic women have undergone profound transformations as a result of this debate. Students are assessed by means of quizzes on the readings, a midterm, a final exam, two papers, and an oral report. In the latter, they have to explain how a leading woman was affected by internal and external forces and was able to overcome the forces holding her back. Some examples include Queen Elizabeth I and Coco Chanel. Sometimes, however, women, such as Marie Antoinette, failed to triumph. Students can also choose to present a man, either a feminist, such as Condorcet or J.S. Mill, or a misogynist, such as Nietzsche and Freud. In their report, students explain the impact that these men had on representations of women. Whereas Mill’s insistence on socialization inspired women to demand their rights, Freud’s depiction of women as neurotics dampened their ability to question scientific theories that portrayed them in a bad light. The quizzes ask pointed questions regarding the impact of internal and external pressures. For example, in a quiz on Vera Brittain, students are asked why she was discouraged from attending Oxford in 1913 and how her nursing experiences propelled her to demand changes in women’s status after World War I. Eighty-five % of the students did very well on that quiz, although the relevant book is four hundred pages. The last quiz is about immigration. This time, about 75% of the students did rather poorly on it, obtaining grades of C or below. The reason was that they were stressed out at the end of the semester and were working on their term papers. There is nothing I can do about this. I will encourage them to hone their time management skills. In the midterm and final, students are asked questions to gauge their understanding of historical change. For example, they are asked why Marie Antoinette was discredited. The proper response is that public opinion turned against her thanks to a campaign to make her into an evil mother by focusing on her alleged lesbianism, incest, and whorish behavior. Students do well on this question, showing their understanding of public relations and propaganda. Eighty percent of the students answered this question well. The rest missed the incest or lesbian aspects because they did not bother to read the essay on the topic by Lynn Hunt and failed to attend the class where we covered the French Revolution. The midterm and final exams ask broad questions. One example is the following: From antiquity to the early nineteenth century, women have faced many obstacles to their advancement. Yet how did they find ways to assert themselves and exert power and/or indirect authority in their intellectual, spiritual (religious), economic, political, and domestic lives? Be sure to touch on all the periods that we have studied 2 (antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, Reformation and the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries). In the fall semester, twelve out of the forty students did an outstanding job on this question, ten did a good job, and the rest fell to a C or below. In the spring semester, ten of the thirtyseven students did superbly, nine got a B, and the rest fell to a C or below. These are fine results. In the final exam, students had to explain how France and England differed in their treatment of women. They had to reflect on the external and internal forces of change. In both semesters, about one-third did very well, and the rest of the students did OK. The spring semester students did worse. The problem is that so many missed the part of the lecture where I went over this question point by point. I did this review after the 7:30 break. Many students don’t stay for the second half. There is nothing I can do about this delinquent behavior. The fall 2011 class was superior to the spring 2012 class. The former had five of our best history majors, who raised the class to new levels and demanded a lot of discussion. Their enthusiasm was contagious. Their intelligence was extremely rewarding. It was one of the best classes that I had ever taught. The spring 2012 class, on the other hand, was held at night and attended by very tired students, who were reluctant to participate and to read books. So many asked if they had to read the “whole book.” I was shocked by their indifference to academics. Fortunately, there were two history majors, one wonderful student from Communication Studies, and a couple of people who added late; they helped prod their fatigued colleagues. The papers also address historical change. The first is an analysis of primary sources. The second is a critique of two European movies. About one-third of the students received a grade of A or B on the first paper, and half received a similar grade on the second. Students find evaluating written documents harder to analyze than movies. (3) What modifications to the course, or its assessment activities or schedule, are planned for the upcoming year? (If no modifications are planned, the course coordinator should indicate this.) I plan two changes. One is to oversee more thoroughly the use of laptops. So many students sit in the back of the class, looking at their laptops rather than listening to lectures. Then they are shocked when they flunk the exam. Another change is to drop the movie The Return of Martin Guerre and replace it with Inch’ Allah Dimanche. The former is about the problem of identity in the early modern period. The latter is about the challenge the Europeans face from immigrants coming from North Africa. Inch’ Allah Dimanche is a comedy that is centered on an Algerian woman who comes to a French provincial town. It shows how external forces lead to change. I think it works better than the movie about the seventeenth century, which I have shown for twenty-two years. I guess it’s time that I change too. I am responding to internal forces, my students’ level of interest in what I try to do. Part 2 3 (4) Are all sections of the course still aligned with the area Goals, Student Learning Objectives (SLOs), Content, Support, and Assessment? If they are not, what actions are planned? Yes. PEH 8/17/12 4