Canons of Rhetoric •

advertisement

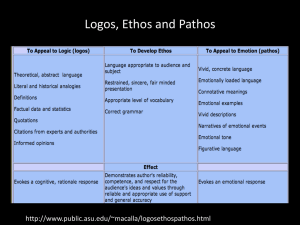

Canons of Rhetoric • Invention: creating and constructing ideas • Arrangement: ordering and lying out ideas • • • effectively Style: developing the appropriate expression/tone for those ideas Memory: retaining invented ideas, recalling additional supporting ideas, and facilitating memory in the audience Delivery: presenting or performing ideas with the aim of persuading Invention • Inventing argument means you are generating • • ideas about a topic. To develop ideas, you can use a range of rhetorical strategies: invoking pathos, using ethos or good character, or employing logos to reason calmly and logically with your readers/listeners. Your task is to forge a powerful text that argues a point, to convince others to see a particular perspective---yours. Invention, con’t. • Photos, like written texts, are artifacts of rhetorical invention. They are created by a writer or artist. Thus, the “reality” that photos display is actually a version of reality created by a photographer’s rhetorical and artistic decisions: – whether to use color or black-and-white film; what sort of lighting to use; how to position the subject of the photograph; whether to opt for a panorama or close-up shot; what backdrop to use, how to crop, or trim, the image once it’s printed. • We are looking at the product of deliberate strategies of invention. Arrangement • After invention, arrangement becomes a key consideration. The way in which you present material on the page will shape a reader’s response to the ideas • When we refer to “arrangement” in a written or visual argument, we often are referring to the underlying structure of the essay itself. – – – – – Chronological structure Cause-effect Problem-solution Block structure Thematic structure Style • Choose appropriate expression for the ideas of your argument. These choices relate to: – – – – – – – – – Language Tone Syntax Rhetorical appeals Metaphors Imagery Quotations Level of emphasis Nuance Style • Your persona is a deliberately crafted version of yourself as the writer. • When you compose a text (written, verbal, or visual), you decide how to use language to represent a particular persona/voice to the audience you want to address. • You create a portrait of yourself as the author of your argument through tone (formal or informal, humorous or serious); word choice (academic, colloquial); sentence structures (complex or simple and direct); use of rhetorical appeals (pathos, logos, ethos); and strategies of persuasion (narration, example, cause/effect, analogy, process, definition). • Creating a persona/voice requires care. • A well designed one can facilitate a strong connection with your readers and therefore make your argument more persuasive. • A poorly constructed voice (biased, inconsistent, underdeveloped) can have the opposite effect, alienating readers and undercutting your text’s overall effectiveness. Alfano, C.L., & O’Brien, A.J. (2008). (2nd ed.). Envision: Writing and researching arguments. Pearson/Longman: New York.