– C N

advertisement

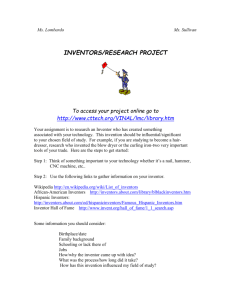

New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 CREATION TO LAUNCH – BARRIERS FACED IN THE INVENTION COMMERCIALISATION PROCESS IN NEW ZEALAND Richard Hadfield Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand richard.hadfield@ird.govt.nz Dr Alan Cameron Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand a.f.cameron@massey.ac.nz Abstract: In recent years political and business commentators have emphasised the importance of invention-commercialisation to New Zealand's future economic prosperity. However, it seems that inventors often face considerable barriers when attempting to get those inventions to market. The purpose of this study is to verify the existence of such barriers, and explore their nature and extent. The research adopted a multiple case study approach. The participants in the research indicated thirty specific barriers experienced by inventors when trying to commercialise their ideas. Some of these barriers were generic in nature, whilst others were specific to the circumstances of the case. The barriers identified were grouped into six categories: patents, government, bureaucracy, finance, the inventor, and other. These categories mirror the general barrier categories found in the literature. These findings suggest that New Zealand's individual inventors do indeed face a wide range of barriers when attempting to commercialise their inventions. Further research is required to investigate the ways in which these barriers can be avoided or overcome. Key words: Entrepreneurship, invention, business start-up, marketing, small business. INTRODUCTION Inventions and their commercialisation are vital to the future success of New Zealand’s economy in the emerging global marketplace. Prime Minister Helen Clark (2002) recently identified innovation as one of the three key elements of the economic policy framework that would carry New Zealand into the 21st century. The Foundation for Research, Science and Technology’s (2001b, p.2) statement of intent for 2001-2004 emphasises the importance of invention commercialisation to New Zealand’s economy by stating “New Zealand must position itself better to develop a sustainable competitive advantage in the new global economy. This means not only developing a culture of innovation, but a culture of ensuring that new knowledge is profitably commercialised or otherwise used to advantage”. Batterham (2001), Australia’s chief scientist, recently urged New Zealanders to consider the importance of new ideas and their commercialisation to the national economy. Patterson (2001, p.1) emphasises that the ideas alone are not enough: The sense of ‘good old kiwi ingenuity’ has always shown that New Zealanders are great improvisers. However, this does not mean we are good innovators. In 1 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal the commercial world, where the bottom line is a large part of the picture, an idea and enthusiasm is not enough to transform it from kiwi ingenuity to a product. Christie (2001) also indicates the importance of invention commercialisation, but laments that New Zealand’s approach to this is sub-optimal. Patterson (2001) affirms this assertion, claiming that New Zealand’s current system of facilitating invention commercialisation is inadequate. Small businesses play an important role in invention and innovation (Cameron & Massey, 1999). In terms of Schumpeterian theory, a hallmark of entrepreneurs is their ability to innovate (Cameron & Massey, 2002). However, individual small business entrepreneurs face greater barriers than their organisational counterparts when trying to bring their inventions and innovations to market. Few studies focus precisely on the experiences of inventors when they attempt to commercialise their creations. According to Amesse, Densraleau, Etmad, Fortier & Seguin-Dulude (1991, p.20) “this is obviously the most important issue, since only the actual commercialisation of inventions will allow society to derive concrete gains from the patent system”. Despite exploration of New Zealand’s individual inventors in the popular press and literature, there has been little empirical research that focuses on the barriers faced within the commercialisation phase of the inventions. This study aims at identifying these barriers and explores the nature and extent of the barriers identified. THE LITERATURE The phenomenon of innovation has been well rehearsed in the literature for some time. Economic and social commentators (such as Crocrombe, et al., 1991 and Batterham, 2001) have commented on the importance of innovation to New Zealand’s economic growth. However, the field of innovation consists of a wide array of separate disciplines. One of these disciplines is the study of invention. Invention is thought by some researchers (such as Damanpour & Evans, 1984) to be a component of innovation, whilst others (such as Bradbury, 1989) consider it to be a phenomenon that precedes innovation. Irrespective of how these two phenomena are conceptually related, invention often acts as a catalyst for successful innovation. However, it seems that individuals with inventions face considerable barriers when attempting to get those inventions to market (Bridges & Downs, 2000). Little empirical research has been conducted to identify these barriers in New Zealand. Consequently most knowledge of this topic is derived from overseas academic studies on related topics (such as those conducted by Kassicieh, Radosovich & Banbury, 1997 and Ammesse, et al., 1991) and books or articles aimed at a general audience (such as Bridges & Downs, 2000 and McGuinness, 1993a,b). Five main barriers to invention commercialisation identified in the literature are: the patent process, lack of finance, lack of entrepreneurial skill, lack of government support, and bureaucracy. Although these paramount barriers have been identified, little information exists on less common barriers. This paper endeavours to establish to what extent barriers to commercialisation in New Zealand are those commonly found elsewhere and the nature of any barriers that may be unique to New Zealand. 2 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 METHODOLOGY The research was conducted using the case study approach. Multiple cases were researched. The evidence gained by this method is generally sound, with the consequence that such studies are generally regarded as being more robust (Herriott & Firestone, 1983; Yin, 1994). Five New Zealand inventors were interviewed and information gathered in each interview was analysed and tested in subsequent interviews. This method follows the grounded theory approach to research, which aims to identify and test common themes, patterns and diversity in the topic (Gilgun, 1992). While the sample was not chosen on a random basis, it attempted to be a representative group. Details of the participants are shown in Table 1. Gender Age Nature of invention Inventor A M 40s undisclosed Inventor B M 50s adventure facility Inventor C M 40s Safety testing technology Inventor D M 70s medical equipment Inventor C F 20s undisclosed Stage reached in commercialisation of invention Prototyped, currently seeking finance and assessing manufacturing requirements. Prototyped, patented, financed, business established and expanding. Prototyped, patented, financed, in negotiation with potential clients. Prototyped, patented, financed and extremely successful worldwide. Currently seeking finance for comprehensive technical assessment. Product not yet patented or financed. Table 1 The interviews were loosely structured in order to maintain flexibility, understanding and cooperation (King, 1994; Easterby-Smith et al., 1991; Sekeran, 1984). The topic guide approach, advocated by Easterby-Smith, et al. (1991) and King (1994) was adopted within the interviews. The topic guide was a list of barriers, which had been identified in the literature as well as interviews with other participants. Coding and analysis of each interview took place before subsequent interviews were conducted, in line with the grounded theory underpinnings of the research design. New barriers identified by participants were added to the guide list for subsequent interviews. Once the data had been analysed and classified into categories, a case report was written up for each participant. The report outlined the thoughts on the barriers faced by individual inventors in the commercialisation process. Quotes from participants were used to support and illustrate assertions, following the example of Marriott & Marriott (2000). Once the case reports had been written up, content analysis was used to identify barriers encountered when trying to commercialise their inventions. 3 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal INVENTOR A Inventor A has invented a number of technical products. His present invention is at a sensitive stage of commercialisation, having not yet been patented, so the specifics are not disclosed. Inventor A believes that the greatest barrier to individual invention commercialisation is the inventor. The naivety of lone inventors, the belief that all they need is a good idea, is their greatest liability. Lone inventors become too protective of their ideas: They want the money, they want the limelight, but they’re not prepared to let their baby go. You have to let your ideas go for them to see the light of day. However, most inventors do not do that, with the result that many inventions never get out of the owner’s mind. According to Inventor A, “A little bit of a lot is more than all of nothing”. Inventors generally have to trust someone with their invention somewhere along the line. Inventor A contends that many inventors do realise this, but their ego overshadows logic: Inventors in the end usually cut off their nose to spite their face; they simply say: “I’m not going to let anybody see this invention because they’d steal it” and that makes them feel good because it empowers them to know they have an invention others can’t see. It’s about power, greed and self-gratification. Most inventors who have had some success seem to have done so largely because they have been willing to share more and more of the proceeds from the product’s success. Many individual inventors resent the compensation required by those involved in the commercialisation process. Many inventions never reach the market because the creator cannot or will not invest money, but cannot accept that somebody else will make money out of the invention. Inventor A proposes that a narrowness of focus, a lack of communication, and the failure to use internal and external networks are significant psychological barriers for the individual inventor, but he also contends that these are self-imposed barriers that inventors themselves create by not sharing their ideas. “Lone inventors don’t communicate or share, because that would compromise their creative genius – ‘I created this all by myself, I did everything’”. He believes that it is the inventor’s self-imposed isolation from the business environment that often prompts these barriers: “The commercialisation process involves a myriad of people, but individual inventors do not hook up with these people, and do not even know about them. They are not even fully aware of the process and what it entails”. But even if lone inventors are able to overcome the barrier of reluctance or inability to communicate and network, they are likely to face problems of integration: There is ignorance on the side of the inventors, but there’s also ignorance on the side of the financiers, bankers, manufacturers and marketers – how can you put all of that together without effective communication? We need to work together. None of us is as smart as all of us. 4 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 Another common barrier within the invention commercialisation process is derived from what Inventor A refers to as ‘backwards marketing’. Instead of identifying a market need and then developing a product to satisfy that need, they develop a product and embark on a great search for someone who wants it. Such products inevitably fail: Inventions often come out of necessity, but where there isn’t a well defined, acknowledged need, a solution to a non-existent need is not going to be a marketplace success. It’s like Victor Borg’s joke about his uncle who invented a cure for which there was no disease. An inventor coming up with a product for which there was no market need is the same. Inventor A believes that research must be conducted not only to identify the nature of the invention’s market, but also to survey the products that already exist. Often inventors try to market an invention designed to fill a niche for which a product already exists. A barrier inherent in the psyche of lone inventors is the belief that they have got to invent something new from scratch. Inventor A contends that modifications of existing products can be far more effective: Making modifications is often the clever thing. That is what adds value. The person who invented the hairpin did not do very well. But the person who put little wiggles in it so it didn’t fall out of one’s hair was the person who made a fortune. Lack of business experience is often a considerable barrier to success for individual inventors. Despite their creativity, lone inventors often lack many pieces of the puzzle such as financial wisdom and entrepreneurial talent. However, Inventor A also emphasises that they are inventors, and should not necessarily be expected to know a great deal about business: You don’t expect world-class violinists to also play the clarinet and tuba equally well. They are violinists, that’s what they do – and inventors invent, marketers market, and manufacturers manufacture. Inventor A considers that the lack of finance available for speculative ventures is a significant barrier to individual inventors. However, he does understand the financial community’s reluctance to finance inventors, because more money is lost than is ever made on inventions. Most financiers will require the inventor to match their investment dollar-for-dollar. But this rate of leverage is not a realistic option for many individual inventors. But the leverage rate that inventors can afford is not a realistic option for venture capitalists, given the risk involved: “If you need $50,000 and you’ve only got $5,000, you’re seldom going to find somebody willing to put up $45,000”. According to Inventor A, the patent process is often an overwhelming barrier for individual inventors due to the costs involved. It can cost the applicant from $15,000 to $115,000 to obtain a patent on a process or product. Inventor A feels that the greatest problem inherent in the patent system is that it places the legal onus on holders to protect their patents. Large companies are able to exercise their rights through the legal system, but the same cannot be said for those without the vast financial resources required to sustain a legal battle. 5 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal INVENTOR B Inventor B is the inventor of a facility aimed mainly at the adventure tourism industry. After designing and implementing the facility in New Zealand, expansion is now focussed on overseas markets and an operation is now under way in a major overseas country. Inventor B now feels he is on the edge of a break-through in the project’s progress. Before the invention and implementation of the adventure concept, Inventor B owned a successful property speculation business. This business made him a lot of money, particularly in the 1980s. Inventor B has not suffered from any lack of business skills in developing the adventure project. In fact, he has found the business side of things easy so far in commercialising his invention. “I was over fifty when I thought of this concept, so I had some resources as well as my share of knock-backs”. Inventor B feels very strongly about the impact that his personal wealth has had on the success of the adventure project: If I hadn’t had any of my own money, then this would never have happened. I might have put the whole idea together and got so far, but then it would have stopped, and that would have been it. There’s that period in-between concept and market when you potentially make or break the product, a period when you’re earning nothing and if you don’t have the resources, you’ll fail. Despite his personal resources, Inventor B believes that it would have been better to bring in more finance at an earlier stage. If he had involved his current partner on the project two years earlier, success would have come much sooner. Inventor B concedes that the project only began to gain momentum after he accepted that he would need the assistance of others. According to Inventor B, giving others a slice of the project is also a question of spreading the risk, of getting capital from people who have the resources, and giving them a share in the responsibility for its success. Inventor B feels that inventors’ perceptions of their product can taint reality for them. Because inventors are often independent by nature, they are unprepared to give away a share of the product, so their prospects wither away. “If I’d brought in other investors earlier in the piece, I would have been more successful”. The personality traits that make a person devote time and effort in inventing something, tinkering and playing with it, and spending much time, money and effort on it, these are often not the sort of qualities to be held by someone who is going to say “I’ve got this great idea, you want to buy half?” But at the same time, Inventor B warns, the willingness to acknowledge what others suggest must be balanced by a belief in one’s self. A lack of personal conviction can be as much of a barrier as an excess of it. The major cost-related barriers for Inventor B were development, marketing, and patenting. Development costs were particularly high for the adventure project, as the activity’s implementation relied heavily on design and engineering. 6 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 Patent costs were a considerable barrier to the commercialisation of the adventure project concept. These included patent attorney fees, fees to patent authorities, both in New Zealand and overseas, renewal fees, and fees to international patent conventions. Inventor B considers that there is little sense in commercialising a concept unless it is protected. However, he also believes that there is little that a small company can do to protect an invention from intellectual property theft from those with the resources to get away with patent infringement. Inventor B considers the current tax rates to be a barrier not only to individual inventors, but also to all New Zealanders: “It’s absolutely outrageous. It’s a big brake on the economy, on enterprise, on industry and on my enterprise”. Inventor B considers the government’s heavy influence on business in New Zealand to be “oppressive”, “pervasive” and “arrogant” and he has no desire for assistance or grants from the government: I just want the government to stay away from me so I can do what I’m trying to do, but instead it interferes, gets into your business, and gets into your pocket. The government here is just so ubiquitous - you can’t get away from it. Inventor B claims that if someone from overseas asked him for advice on business in New Zealand, he would advise him or her to go to another country, such as Australia or the United States. INVENTOR C Inventor C has invented a technological system designed to save costs in the transport sector. He found that crude forms of the technology had been investigated in Britain and USA. Inventor C’s ingenuity was in the adaptation of this technology to a different context - mainly by allowing safety tests to be done cheaply in situ, rather than expensively in the lab. Inventor C believes that the costs inherent in the system pose a significant barrier to inventors. The provisional patent on Inventor C’s system cost approximately $1 400. This gave Inventor C a year’s protection without the obligation of disclosure. At the end of this time he was required to decide whether he would file for a full patent. After the provisional patent expired, Inventor C made a PCT (Patent Co-operation Treaty) claim, which cost $8 000. This claim theoretically gave Inventor C two years of protection within the PCT’s member countries. To take out patents abroad is costly. Inventor C was required to separately patent a number of items and processes incorporated into his system. Inventor C has relied heavily on patents in protecting his invention, as he believes that patents are vital to the commercial survival of a product originating from the individual context: You have to patent. Some people think you don’t need to do it, but if you don’t you’re going to fail quickly. When you see my system, you only need to take a glance at it and you can make it yourself if you know what you’re doing. When Inventor C deals with larger companies, he relies on both patents and confidentiality agreements for protection. Inventor C strongly advocates confidentiality agreements as a means of protection against intellectual property (IP) theft, claiming that “confidentiality 7 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal agreements are a lot tighter than patents, and they give you more control”. Inventor C argues that confidentiality agreements eliminate the need for large amounts of money if legal action is required. To counter the threat of IP theft, Inventor C has also allied himself with a larger company. He has an arrangement with an Australian transport company for exclusive distribution rights to his product. By giving this company an equity interest in the product, it is also in their interest to protect the product from patent infringement. But they also require full patents to be issued and regularly maintained. As a result, patenting costs have escalated to become the most significant cost-related barrier faced by Inventor C. Inventor C considers that networking and communication are vital to the success of invention commercialisation. He claims that networking played a major role in the initial stages of his invention’s commercialisation: “The moment I get on to something, I think ‘who can help me here?” However, equally important is management: “You need somebody who can direct the ideas”. Many of Inventor C’s contacts were gained through a local engineer who was skilled in project management and had technical knowledge, whilst also possessing a network of polytechnic and business contacts. These contacts were extremely helpful and contributed significantly to the project. In Inventor C’s opinion, networking and business know-how are essential to success. “Some inventors do not have that ability or willingness to get in touch with those who could help them. In addition, most inventors don’t have the foggiest idea about going into business, marketing, financing, and so forth. I think that is a major barrier.” Inventor C states that some academics can be a barrier to the commercialisation of technical inventions due to the conflict between theoreticians and practitioners. While the metallurgy academics that Inventor C dealt with had sound theoretical knowledge, he believed that they lacked the ability to develop practical solutions to technical problems. Inventor C conjectures that academics felt threatened by his ability to apply the theory in an innovative way and strongly questioned the validity of his claims. Although Inventor C was prepared to work with academics, he felt that they resented him for discovering the concept first. The vested interest of others is such that they don’t take kindly to outsiders coming in and pointing out that there could be another way. This is a huge barrier. It’s a system that assumes you must protect your patch somehow. It’s an arrogant assumption that an outsider can’t come up with a better idea. In the opinion of Inventor C, government assistance in New Zealand could do more to expedite commercialisation of inventions. He attempted to gain funding from the Technology for Business Growth (TBG) programme, but found this to be problematic. He had difficulty gaining access to the funding because he was an individual inventor rather than a company. The TBG programme is focussed on helping technology-based companies to employ more people. Inventor C believes that he was not eligible because he was an individual - a “one man band”. 8 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 Inventor C considers financial difficulties to be a huge barrier for individual inventors. He estimates that he has spent in excess of $200,000 on developing and marketing his invention. Most of the funding for Inventor C’s project has come from a personal inheritance, without which it would never have reached its present stage. Inventor C believes that obtaining venture capital can be problematic for inventors. When inventors make agreements with venture capitalists, they become bound by that agreement. This can put the inventor in an undesirable situation: Venture capitalists will inevitably want a return. It’s not always the best thing to be involved with people who want a pound of flesh out of you at the end of the day. It might work for some people but for inventors it’s no good. They don’t want the pressure of it. They need to be free to work through their ideas and not have to be worried about paying back money. INVENTOR D Inventor D is a long established serial inventor. In the 1960s Inventor D identified a gap in the health sector and began inventing specialised equipment to fill this gap. Since then, Inventor D Ltd has grown to become a substantial manufacturer of medical equipment, exporting to a wide range of countries. Much of the company’s success has come from Inventor D’s ability to constantly invent new products to satisfy the market. Inventor D believes that although many people will invariably be involved in an invention’s commercialisation, in the end, the product’s success will rest in the hands of one individual – the inventor: I have only ever found one answer - you have to do it yourself. You have to make the product, you have to market it, you have to finance it, and you have to coordinate the whole process. There just isn’t any other way. If the inventor does not have the skills required to co-ordinate the product’s commercialisation, then it will inevitably fail. Lack of business and project management skills often presents an ongoing barrier to individual inventors when attempting to manage an invention’s commercialisation. Inventor D also believes that the right attitude to business is just as important as business skills. From the outset, Inventor D followed some very definite rules of business. All suppliers got paid on the 20th of each month. On the 30th of every month all other accounts payable went out, regardless of all other operations. Inventor D kept these principles and priorities in mind throughout the establishment and growth of the company, ensuring that the business remained, in his words: “tight and clean”. Fiscal prudence has helped ensure success. Inventor D began his business with the help of a ₤200 loan from his father and a small amount of his own savings. ₤150 was put towards engineering equipment used to manufacture the product, and the remaining ₤50 was used to open a bank account. Inventor D has not gone below this ₤50 bank balance, but has instead “inched it upwards and upwards”. The company operated for forty years without an overdraft. Eventually Inventor D grew the company to a point where he did not feel comfortable unless it had a bank balance of $100 000. This maintenance of a contingency 9 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal fund has been an underlying principle of Inventor D’s business philosophy. Inventor D believes that many self-employed inventors are not careful enough financially. However, he also concedes that it may be more difficult now to commercialise an invention with limited resources now than it was in the past. Inventor D conducted market research for his products before he began designing them. Because Inventor D designed his inventions to fit the needs of the market, he was able to ensure a greater likelihood for market acceptance of his products. In the late 1970s Inventor D realised that in order to grow, the company needed to expand into overseas markets. The process was not cheap. Inventor D initially spent $120,000 on entering his products in a healthcare exhibit in Germany. He has subsequently entered his product range in exhibitions all over the world, in order to establish them on the global market. Inventor D had the funds required to do this because he had built up a sound domestic market run on a sound financial basis. Patents have cost Inventor D a great deal over the last forty years. Patent renewals have become increasingly expensive and the time between each one has become shorter. Patent costs imposed a huge burden on him, as he increasingly relied on offshore markets. Patents were registered in many countries including Germany, France, Sweden, UK, and the United States. Inventor D is sceptical about how effective patents really are at protecting lone inventors from intellectual property theft. “In the final analysis, my experience indicates that a patent’s worth is negligible”. He considers that, in effect, there is no real protection for individuals, and this is a major barrier for them. Large companies can ignore small businesses on the other side of the world, and continue to infringe on their patents in the knowledge that there is little that the patent holder can do to stop them. Inventor D claims that numerous companies have copied his patented designs, including some based in New Zealand. However, such patent infringements have generally been unsuccessful because Inventor D has continually stayed a few steps ahead of the competition: My answer has always been not to fight it, but to redesign and go a step over the top of the competition. If they’re copying your current product range, you redesign and come back with something that leaves them way behind. Inventor D suggests that individuals should go no further than provisional patent registration. The provisional patent provides twelve months’ protection without the obligation to disclose the product to the public. Inventor D asserts that a worthwhile invention is going to be copied regardless of patents. “So common sense says leave it at that. Forget carrying on, because it gets too costly.” Inventor D has now retired. Nevertheless, he remains an inventor at heart, having recently designed and created a wheel-harness for a friend’s dog, which has no back legs. Inventor D still feels the achievement and joy of inventing something of use. “The dog loved it; he was running around here on his new wheels, and that made me glad.” 10 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 INVENTOR E Inventor E is a 29-year-old solo mother with two children and has been on social welfare for many years. In recent years, Inventor E has been involved in development and market planning for a product she invented. However, at the present stage, the product is sensitive to competition and subsequently has not been disclosed within the case. Inventor E believes that the project she is now working on has far greater potential than any of her previous inventions. “My present project is very exciting and extremely achievable.” Inventor E seems to have a firm understanding of what is required to get a product to market. She thinks of the invention as a business project rather than a stand-alone product that will sell itself. According to Inventor E, the project is progressing steadily. She is at the end of the prototype development phase and is currently working on patenting. Inventor E has previous employment experience as a waitress, and has also worked for a marketing company. However, she states that she has never kept a job for any length of time due to her “stubbornness and unwillingness to take orders”. She has no tertiary qualifications but does not consider this lack of education to limit her ability: “I believe that a person’s ability to run a business is not dependent on their level of education”. Having said this, Inventor E concedes that in her experience, other people have not held the same opinion, and this has impacted negatively on her project. Inventor E also feels that her status as a welfare recipient has meant that those she has approached for assistance have not taken her seriously. “When people found out that I was on a benefit they instantly assumed I was stupid.” Inventor E resents this assumption. The treatment that Inventor E received from her Business in the Community mentor appears to typify this stereotyping. Inventor E states that her mentor was extremely dismissive of her abilities and the worth of her invention: My ‘mentor’ laughed at me then walked out the door, because I was not as adept in business as she had expected me to be. I found this to be quite ironic, considering her role was to develop these skills in me. As a welfare beneficiary, Inventor E’s main dealings with the government have been through Work and Income New Zealand (WINZ). Inventor E considers that WINZ’s reluctance to provide assistance and funding has been a major barrier to the commercialisation of the invention. WINZ claims that Inventor E’s project does not fit the policy criteria for assistance. However, Inventor E speculates that very few lone inventors’ projects do fit the criteria for assistance. However, Inventor E has obtained help from an independent consultant who was extremely helpful at a minimum cost to the project. She admits that she initially found it difficult to trust the consultant with the product’s specifications, but eventually did so. Inventor E considers that she was lucky to find someone who was willing to assist her without demanding a great deal in return. The inherent difficulty in developing networks and connections is a significant barrier for inventors who are on welfare. However, Inventor E believes that many inventors do not even try to develop these vital networks, thus compounding the problem. Lone 11 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal inventors “often do not know where to start in making connections in the business world”. Nonetheless, developing and using these connections is of vital importance to success: “Accessing the right people is difficult, but also important”. Inventor E has found academics to be extremely helpful and forthcoming with their time and advice. Inventor E contends that if she hadn’t had the help of certain university engineers and their contacts, she would not have made so much progress. “I probably would have given up trying by now. I owe more to them than to any other group because they encouraged me and took the time to help me.” Inventor E has found the costs of invention commercialisation to be very high, with the result that she continually has had to compromise on the project. The only way Inventor E could cover the costs was to carry out the project over a long period of time. This way she could build up savings from her welfare benefit to fund the project. Inventor E’s invention is currently at the end of the research and development phase. It has not yet been patented, manufactured, or marketed. Consequently the project’s costs may soon grow beyond Inventor E’s means, irrespective of the lengthened time frame. Recognising this, Inventor E has made concerted efforts to obtain financial assistance from a wide range of sources. Inventor E quotes Ernest Rutherford to indicate her attitude to financing the project: “I have no money, so I’m going to have to think harder”. Inventor E has approached WINZ, BizInfo and a number of banks and venture capitalists, all to no avail. Inventor E felt that she was being pushed around from one to the other. Venture capitalists approached were willing to offer finance, but at an exorbitant interest rate as well as requiring an 80% to 90% equity share of the project. Inventor E was not prepared to accept either of these conditions. Through networking, Inventor E found that government assistance schemes provide access to either ‘matching finance’ or ‘20/80 finance’. Inventor E also identified that some programmes offer research, development and patent cost coverage. However, as these still fall under the matching or bridging finance schemes, they still represent a barrier to a welfare beneficiary: A person like myself is not able to access the funding provided by these schemes, as I do not have the money to qualify for acceptance. 20% of $50,000 is still quite a bit for someone on the Domestic Purposes Benefit. Inventor E has found a source of finance in a government assistance scheme that is prepared to help with patenting costs. However, this deal may fall through because the agency is reluctant to sign a confidentiality contract, which Inventor E considers to be vital, as the invention is as yet unpatented. Inventor E feels that with the invention unpatented, she is stuck in a ‘Catch 22’ situation. The only thing she has to protect her product from theft is confidentiality agreements: I have come across a couple of people and thought to myself “Oh no, they do not feel right”. But what can you do? Keep your mouth shut and never get anywhere, or say something with a confidentiality agreement and pray the person doesn’t go off and steal it, knowing that you don’t have the resources to take him to court. 12 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 Inventor E views confidentiality agreements with the same scepticism as she does patents: “I don’t have the resources to take a company to court, for breach of contract, for patent infringement, for anything”. Inventor E suggests that a confidentiality agreement is unlikely to deter a large company from stealing an invention. She comments that some large Asian companies hire people to search patents in New Zealand and Australia, then adapt the technology to their own design and flood the market. Furthermore, Inventor E feels that deficiencies in the New Zealand legal system are at the core of the problem, claiming that, “New Zealand patent laws are very outdated and need to be revised to provide more comprehensive protection to inventors and their inventions”. RESULTS The participants in the research identified thirty specific barriers to individual invention commercialisation in New Zealand, illustrated in Figure 1. This indicates that there is a wide array of barriers faced by New Zealand’s inventors in the commercialisation of their inventions. Some of these barriers were generic in nature, whilst others were specific to the circumstances of the inventor. The barriers identified were grouped into six categories: patents, government, bureaucracy, finance, the inventor, and other. These categories mirror the generic barrier categories identified in the literature. 5.2 Barriers identified: Frequency across cases 5 1 gulati ons Safety and H ealth gover nmen t bure Resou aucrac rce M y anagem ent A Emplo ct (19 ymen 91) t Relat ions A ct (20 00) Lack of tru st / R Self-im el uctan posed ce to isolati share on fro Unbal m bu anced siness perce env... ption of the Lack inven of per tion sisten Lack ce an of bu d ten siness acity exper ience and sk ills Local Tax ra te in com panie s Safety re pation al Occu cracy Bureau ernm ent fu nding ernm ent as sistan and In ce come New Zeala Gover nd nmen t Inte rferen ce Work of go v of go v Lack Lack Fragm Paten ented t cost world s wide Lack paten of pro t syst te ct em io Paten n pro t laws vided not re by pat cognis ents ed in some count. .. 0 Difficu lt 2 y in n etwork ing an Busin d com ess in munic the co ating mmu Busin nity m ess co entor mmu schem nity's e assum ption s abo ut ed Veste ucatio d inte Media n and re , spec st of benef ifically other iciaries Backw s televis ards m ion n arketin etwork g / la s ck of Difficu pre-d evelo lties in pmen reach t rese ing th arch e mar ket Acad emics 3 Cost of co mmer cialisat Difficu ion lty in raisin g cap ital Frequency 4 Figure 1 DISCUSSION Patents One of the most significant barriers was that of the patent process, specifically its high cost and lack of protection. The inventors took the issue of intellectual property protection very seriously, as this is the basis on which their success is based. On the whole, the participants 13 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal confirmed the assertion in the literature (Bridges & Downs, 2000; Hopkins, 1999) that patents are extremely expensive and time consuming. Ongoing renewal fees identified in the literature (Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand, 2001) were found to be an ongoing cost barrier to individual inventors when trying to commercialise their ideas. However, on the topic of the worth of patents, there was a certain amount of disparity between the cases. Whilst some participants initially proclaimed the importance of patenting, all were hasty in pointing out the myriad of flaws in the system. The major patent-related barrier identified by the participants aligns with that identified by Husch & Foust (1987) and Schulman (2001), that in the event of a patent violation, the legal onus is on the inventor to protect their patent in court. Inventor A agreed with Husch & Foust (1987) and Schulman (2001), claiming that in this circumstance there is no guarantee that the claimant will win the court case. The participants pointed out that irrespective of the outcome of legal action, the cost of taking a large company to court is beyond the means of most individual inventors, and this represents a substantial barrier to these individuals. Three of the five participants extrapolated upon this in affirming the assertion of Roberts (2000) that geographic barriers compound the problem. Inventor B pointed out, however, that if the claimant did win a court battle against a large company, they could be awarded a great deal of money by the court. On the whole, the participants were extremely sceptical about the ability of patents to protect their inventions. They all concluded that patents, on their own, do little to protect them from intellectual property theft, and this is a significant barrier to the commercialisation of their inventions. In considering the implications of this, a range of suggestions were put forward, including confidentiality agreements, secrecy agreements, and strategic alliances. However, these mechanisms seem as problematic as patents when viewed in their individual contexts, which leaves the barrier of protection costs and difficulties standing. The inventor Inventor C considers the term ‘inventor’ to carry an unwarranted sense of arrogance, claiming that invention is not creation, but the discovery of something that already existed. Inventor A expressed similar sentiments, suggesting that many lone inventors relish the stereotype of ‘eclectic genius’. Inventor A strongly believes that inventors themselves are answerable for many of the problems that arise in the commercialisation process. He argued that some individual inventors become so obsessed with their invention that it clouds reality for them. To bring these opinions into the context of this study, however, the implications of such personality traits must be addressed. According to the participants, the implications of inventors’ attitudes to the commercialisation of their inventions are far-reaching. Inventor A believes that the major problem resulting from inventors’ attitudes is the reluctance to share the inventions with those who may be able to help in their commercialisation. Inventors B and E both conceded that they had problems trusting others with their inventions. Inventor B indicated that this made the commercialisation of his adventure facility more difficult than it would otherwise have been. 14 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 Networking and communication Not surprisingly, the participants supported the assertion in the literature (Kay, 1993; Madique & Zirger, 1988) that the commercialisation process is both complex and difficult to manage. Furthermore, they all felt that inventors in general often underestimate the complexity of the commercialisation process. In light of this, the participants suggested that the lack of networking and communication conducted by inventors throughout the commercialisation process represents a significant barrier to success. The presence of networks is perhaps the most noticeable difference between the corporate context and the individual context. In the company environment, individuals from separate disciplines work together on projects under the organisational umbrella. The individual inventor, on the other hand, is faced with the formidable task of developing and maintaining a network of individuals not only from different disciplines, but also in different organisations. Often the individual inventor is unaware of the need for this network of individuals. Finance All participants identified high costs, linked with the difficulty in obtaining financial assistance, as significant barriers to invention commercialisation. The participants’ opinions aligned with claims within the literature (Technology New Zealand, 2001) that there is no lack of venture capital in New Zealand. The problem, it seems, is the common requirement among venture capitalists for either a high equity share, a substantial deposit on a loan, or both. However, the participants were by no means critical of venture capitalists for their reluctance to fund lone inventors’ projects. The participants agreed with the assertions of Madique & Zirger (1988) and McGuinness (1993a) that the high risk, and corresponding high failure rate of invention commercialisation projects, explains financiers’ reluctance to fund these projects. Inventor A and Inventor B both conceded that if they were venture capitalists they would be just as reluctant to invest in the projects of lone inventors. Three of the five participants indicated that inventors’ reluctance to share hinders external financing of invention commercialisation projects. Venture capitalists usually require an equity share in the projects they finance, but many lone inventors are reluctant to provide this. Subsequently, as Inventor A stated, the lone inventor maintains their 100% share of nothing, having foregone the chance to retain a lesser share of much more. But even if the inventor is willing to forego an equity share in the product, problems arise because investors often require bridging finance for monetary loans. Inventor E indicated that this bridging capital requirement is a significant barrier for her, as she cannot afford the down payment on a loan. Backwards marketing Inventor A commented that instead of identifying a market need and then developing a product to satisfy that need, inventors often develop a product and then embark on a great search for someone who was willing to buy it. Inventor D and Inventor B also claim that this lack of pre-development market research results in a significant barrier to individual invention commercialisation. Often, in instances where pre-development market research was not conducted, the market for the invention never existed. In these instances, huge resources 15 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal are required to get the market to accept the product. Individual inventors usually do not possess huge amounts of resources, so the requirement for push-focussed marketing becomes a barrier to them. Inventor A agreed, claiming that where inventors try to change the market, they often fail. However, it could be argued that assessing the market potential for individual inventions is more difficult that it seems. By its legal definition, a patentable invention possesses complete novelty status. Many of the products developed by lone inventors are revolutionary in their design. Products of this nature are difficult to assess from a marketing perspective, as they cannot be placed within the context of existing product lines on the market. This may present a significant barrier in itself – even if an inventor does attempt post-design market research, they will not reach definite conclusions on the market potential for the product. Bureaucracy Three of the five participants identified bureaucracy as a barrier to individual invention commercialisation. Whilst some of the participants did not directly refer to the existence of this barrier, none of them disputed it. The contexts in which the participants encountered bureaucracy were wide-ranging. Some bureaucracy-related barriers were somewhat generic. For example, Inventors A and C both faced the barrier of being required to spend time and money producing product performance specifications which simply stated the obvious. However, most of the bureaucracy encountered was specific to the context of the invention and its market. For example, the issue of the Resource Management Act (RMA) only arose in Inventor B’s case, as his invention was a facility, whereas the other participants’ inventions were products. Government The stark contrast in participants’ opinions on the responsibilities of government is a notable phenomenon within the study. Inventor E felt that government had a responsibility to fund the commercialisation of individual inventions. Furthermore, she felt that the absence of government financial support presented a significant barrier to individual invention commercialisation. Inventor E has approached various government departments and schemes seeking financial support, and considers their reluctance to provide monetary grants to be her greatest barrier. In contrast, Inventor B believes that the New Zealand government’s attempts to provide support for inventors creates more barriers than it solves. Inventor B believes that speculative ventures such as invention commercialisation should be funded by venture capitalists in return for equity. He believes that government interference and the tax rate pose a significant barrier to inventors-come-entrepreneurs such as himself. This indicates the way in which opinions are inevitably shaped by circumstance. Whilst Inventor E lacked resources, Inventor B did not, and it would seem that this runs parallel to their contrasting opinions on government support. Inventor C and Inventor A considered that whilst government should not be expected to fund invention commercialisation, they do have a responsibility to assist lone inventors in the 16 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 commercialisation of their inventions. They contended that the type of assistance provided by the New Zealand government is of little help to individual inventors, and this represents a barrier for them. Inventor C’s suggestion of ‘inventions factories’ was surprisingly similar to Inventor A’s idea of ‘technology parks’. Both concepts were centred on government providing access to the network of individuals required to bring a product to market. CONCLUSIONS The responsibility for countering the barriers identified in this research rests on both the government and lone inventors. It seems that many of the barriers are derived from overprotectiveness on the part of individual inventors. The unwillingness to interact with others in the process of commercialisation often limits the product’s potential to the business abilities of its inventor. This is a problem, as lone inventors are often severely lacking in entrepreneurial ability. The only avenue out of this conundrum is the willingness to forego partial control and ownership of the invention, in return for the assistance of others. A huge network of individuals will inevitably be required to bring a product to market. Government can make this network more accessible to inventors, but it cannot make them use it. This decision will continue to rest upon the shoulders of lone inventors. There is no doubt that New Zealand’s individual inventors face barriers when attempting to commercialise their inventions. However, a lack of research on exactly what these barriers are, make it difficult for those in the business realm to help lone inventors in their plight. The type of help required, is also difficult to determine, as the true nature of the barriers faced is not clearly understood. This research never aimed to provide generalisable explanations for the failure of lone inventors. Likewise, it is not the aim of this report to make practical suggestions on how commercialisation barriers can be overcome or avoided by individual inventors. It is hoped, however, that the study’s results will set a basis for further research that will provide practical suggestions for lone inventors and the government on how the barriers can be overcome or avoided. LIMITATIONS The most significant limitation of this research lies in the small sample size, which means that findings are not representative of the population. The aim is to give an indicative impression of the relevant barriers. 17 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal REFERENCES Amesse, F., Desranleau, C., Etmad, H., Fortier, Y. & Seguin-Dulude, L. (1991). The individual inventor and the role of entrepreneurship: A survey of the Canadian evidence. Research Policy, 20(1), 13-27. Batterham, R. (2001, August). Innovation and creativity. In J. Hood & H. Clark (chairs), Innovation and learning transformations. Paper presented at the Catching the knowledge wave conference, Auckland, New Zealand. Available URL: http://www.knowledgewave.org.nz/documents/talks/Batterham. Bradbury, J. A. A. (1989). Product innovation: Idea to exploitation. Great Britain: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Bridges, J. & Downs, D. (2000). Number 8 wire. Auckland: Hodder Moa Beckett. Cameron, A. & Massey, C. (1999). Small and medium sized enterprises: A New Zealand Perspective, Auckland: Longman (with Claire Massey) 1999. Cameron, A. & Massey, C. (2002). Entrepreneurs at work: Successful New Zealand Business Ventures, Auckland: Prentice Hall (with Claire Massey) 2002. Christie, R. (2001, August). Speech to the ‘Catching the Knowledge Wave Conference’: Introductory address. In J. Hood & H. Clark (chairs), Innovation and learning transformations. Speech presented at the Catching the knowledge wave conference, Auckland, New Zealand. Available URL: http://www.knowledgewave.org.nz/documents/talks/Christie Clark, H. (2002). Growing an innovative New Zealand. Available URL: http://www.med.govt.nz/irdev/econ_dev/gainz/index.html February 12th, 2002. Crocrombe, G. T., Enright, M. J. & Porter, M. E. (1991). Upgrading New Zealand’s competitive advantage. Auckland: Oxford University Press. Damanpour, F. & Evans, W. (1984). Organisational innovation and performance: The problem of ‘organisational lag’. Administrative science quarterly, 29. 392-409. Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R. & Lowe, A. (1991). Management research:Aan introduction. London: Sage. Foundation for Research, Science and Technology (2001b). Statement of intent for 2001-2004: Investing in innovation for New Zealand’s future. Wellington: Author. Gilgun, J. F. (1992). Definition, methodologies, and methods in qualitative family research. In J. Gilgun, K. Daly & F. Handel (eds.), Qualitative methods in family research. Newbury Park: Sage. Herriot, R. E. & Firestone, W. A. (1982). Multisite qualitative research in education: A study of recent federal experience. Unpublished. Hopkins, J. (1999). Inventions from the shed. Auckland: Harper Collins. Husch, T. & Foust, L. (1987). That’s a great idea: The new product handbook. Berkley: Ten Speed Press. Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand (2001). Annual Report for 2000-2001, IPONZ. Wellington: Author. Kassicieh, S. K., Radosevich, H. R. & Banbury, C. M. (1997). Using attitudinal, situational, and personal characteristics variables to predict future entrepreneurs from national laboratory inventors. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 44(3), 248-257. Kay, J. (1993). Foundations of corporate success: How business strategies add value. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 18 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 King, N. (1994). The qualitative research interview. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (eds.), Qualitative methods in organisational research: a practical guide (pp 14-36). London: Sage. McGuinness, M. (1993a). What investors want to see. New Zealand engineering, Nov., p. 12. McGuinness, M. (1993b). There’s still money lonely for a home. New Zealand engineering, Nov., p. 15. Madique, M. A. & Zirger, B. J. (1988). The new product learning cycle. In K. Grnhaug & G. Kaufmann (eds.), Innovation: A cross-disciplinary perspective (pp 407-432). Oslo: Norwegian University Press. Marriott, N. & Marriott, P. (2000). Professional accountants and the development of a management accounting service for the small firm: Barriers and possibilities. Management accounting research. 11, 475–492. Patterson, E. (2001, August). Innovation and creativity: Bringing it all together. In J. Hood & H. Clark (chairs), Innovation and creativity. Theme paper for the Catching the knowledge wave conference, Auckland, New Zealand. Available URL: http://www.knowledgewave.org.nz/documents/Innovation and Creativity.pdf Roberts, B. (2000). The muddle of invention. Electronic Business, 26(1), 72-80. Schulman, S. (2001). Patent pollution. Technology Review, 104(6), 39-40. Sekeran, U. (1984). Research methods for managers: A skill building approach. New York: Wiley. Technology New Zealand (2001). Webpage. URL: http://www.technz.co.nz. October 24 th, 2001. Yin, R.K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, USA: Sage. 19