C : W ?

New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research Volume 1, Number 1, 2002

C HINESE STUDENTS : W HY DO THEY COME AND HOW CAN WE HELP THEM

SUCCEED

?

Pam Malcolm

School of Accountancy, Law and Finance

UNITEC

Auckland, New Zealand pmalcolm@unitec.ac.nz

Anthony Ling

School of Accountancy, Law and Finance

UNITEC

Auckland, New Zealand aling@unitec.ac.nz

Abstract: There has been a huge increase in the number of international, full-fee paying students enrolled in New Zealand tertiary institutes in the last eight years. In

2001 the International student market contributed an estimated $1 billion to the NZ economy and earned as much foreign exchange as the wool industry and four times that of the wine industry.

Although, overall, International students only constitute approximately 4% of the total student body at NZ tertiary institutes, in many main-centres this number appears much higher.

In 2001 approximately forty-one percent of International students came from China.

This has increased from less than 2% in 1994. In this paper we have investigated why there has been such a dramatic increase in the number of students from China.

The primary reasons are the ease of obtaining a visa and the low cost of fees.

We also investigated what Chinese students liked, disliked and thought could enhance their learning experience. Our investigation revealed that students enjoyed the low cost of living and low fees plus the weather and the general environment but felt that New Zealand was too quiet and boring. To enhance their learning experience students requested additional language support and extended library opening hours to enable them to study in a quiet environment away from crowded student accommodation or homestays.

As students’ language proficiency improves their grades will also improve. Students have tried to improve their English by watching television and speaking with classmates in English.

It is important that international students and teaching staff are supported. Initiatives introduced include extensive training for staff and additional class contact hours, help clinics and on-line resources for students.

Key Words : NESB, China, Chinese students, cost of living, EAL, full-fee paying students, New Zealand, public tertiary institutes, retention, studying destination, success, tuition fees.

I NTRODUCTION

The international student market is one of New Zealand’s highest export earners and last year contributed an estimated $1 billion to the NZ economy (Evans, 2002). This market (overseas students) now earns New Zealand as much foreign exchange as the wool industry and four times that of the wine industry (Gamble & Reid. 2002).

In public tertiary institutes more international students are studying business and commerce courses than any other discipline, (Ministry of Education, 2001), with twenty tertiary

1

Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal providers in New Zealand offering places in the NZDipBus to international students

(Education New Zealand Trust, 2002).

Forty-one percent of international students studying in New Zealand in 2001 came from

China (Ministry of Education, 2001). It is important that lecturers and academic mangers are aware of why Chinese students choose to study in New Zealand and what can be done by

New Zealand tertiary institutes to make their study more enjoyable and successful.

R ESEARCH O BJECTIVES

With the increasing number of full-fee paying (FFP) students from China, our research aims at getting answers to the following questions, to assist educational providers to better meet the needs of students:

Why do Chinese students choose New Zealand as a studying destination?

What are the objectives of their study?

What problems have they encountered during their stay in New Zealand and what do they think that educational providers can do to make their study easier and more successful?

L IMITATION OF THE R ESEARCH

The targeted respondents of the survey are those FFP Chinese students doing NZDipBus at

UNITEC. The population size of this study is relatively small, given the total number of

Chinese students enrolled in the public tertiary institutions in New Zealand.

R ESEARCH M ETHODOLOGY

The research for this paper was interpretive in nature as the authors were investigating why students had decided to study in New Zealand and at UNITEC, a public tertiary institution, and what could be done to improve their learning experience.

Qualitative and quantitative primary data was collected from three sources. Eight students attended a focus group. The responses to the focus group discussions lead to the formation of a questionnaire that was given to two groups of Chinese students. The first group of 27 students were students in at least their second semester of study in the NZDipBus at

UNITEC. This survey was done in early October 2001. The questionnaire was altered slightly to simplify the data gathering process and delivered to a second group of 52 students who were surveyed in their second week of study in the NZDipBus at UNITEC in February

2002.

There were five sections in the questionnaire. The first section collected personal information about the students’ gender and age. The second section of the questionnaire requested information from the students about their highest academic qualification before applying to do the NZDipBus, the discipline of their highest qualification and any previous work experience. The third section asked students what their plans were after they finished the NZDipBus. The fourth section related to issues concerning their choice of UNITEC as a

2

New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 place to study and what students like, dislike and the problems with their study at UNITEC.

The final section asked students how they had tried to improve their English and how they felt UNITEC could make their study more successful.

Statistical information was obtained from student enrolment databases at UNITEC. Journal articles, government web sites plus New Zealand and Chinese newspapers and periodicals provided background information for this study.

F ULL F EE P AYING S TUDENTS

As of July 2001, there were 12,651 full-fee paying (FFP) students enrolled in public tertiary institutions. Asia is the main source region and accounts for more than 80% of all FFP students enrolled in public tertiary institutions (Table 1).

Pacific

Asia

North America

Central & South

America

Africa

Europe

Middle East

Not Stated

Total

1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

338 387 462 578 604 615 817 741

3,322 4,076 5,568 6,697 6,241 6,664 9,100 10,546

166 214 267 306 382 484 639 459

15 19 20 28 38 49 62 56

28 28 31 37 63 75

180 204 263 323 352 528

21 19 24 21 19 20

622 293 92 99 51 157

82

757

41

97

680

70

2

4,692 5,240 6,727 8,089 7,750 8,592 11,498 12,651

Ministry of Education, (2001)

Table 1 Number of FFP Students in Public Tertiary Institutions by Region for Period from 1994 to 2001

China is the leading provider country in Asia (providing 5,237 students), followed by

Malaysia (1,126), Japan (766) and South Korea (753). The current figures show that China accounts for more than 40 per cent of the total number of FFP students enrolled in public tertiary institutions in New Zealand. The increase in student numbers from China is dramatic, from 55 in 1994 to 5,237 in 2001 (Table 2).

China

Japan

Korea

Malaysia

Other

Total Asia

1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

55 61 82 88 127 720 2,894 5,237

643

154

546

218

806

352

1,240

585

1,175

427

1,103

533

1,159

778

766

753

1,191 1,844 2,508 2,769 2,332 1,913 1,630

1,279 1,407 1,820 2,015 2,180 2,395 2,639

1,126

2,664

3,322 4,076 5,568 6,697 6,241 6,664 9,100 10,546

Ministry of Education , (2001)

Table 2 Number of FFP Students in Public Tertiary Institutions by Countries of Origin (Asia)

3

Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal

The above figures do not include those international students enrolled in private tertiary institutions, such as English language schools. According to figures released by the Ministry of Education, as at 31 July 2001 there were another 3,294 FFP students enrolled in private tertiary institutions. Of these 1,206 were from China (Ministry of Education, 2001).

According to an optimistic forecast by the Ministry of Education, the FFP student numbers enrolled in public tertiary institutions by 2005 will almost double the 2001 figures and will reach 21,865 (Ministry of Education, 2001).

In addition, there were 10,555 FFP students enrolled in primary and secondary schools in

2001. At secondary school level, there were 3,554 Chinese students, up from only 43 in 1996

(Gamble & Reid, 2002). An assumption can be made that a large number of these may decide to continue their tertiary education in New Zealand.

Statistics released by Ministry of Education in June 2001 show that 31.9% of the FFP students selected commercial and business as their field of study (Ministry of Education,

2001).

In 2000 UNITEC had the highest number of FFP students (1,664) of any public tertiary institution in New Zealand (Ministry of Education, 2001). Many of these students came to

New Zealand to study business and chose the NZDipBus as their first qualification.

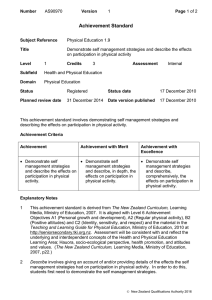

In 2002 students of 29 nationalities enrolled in the NZDipBus at UNITEC. By far the highest proportion of international students came from China. At UNITEC there were no international students from China enrolled in the NZDipBus before 1997. In May 2002 there are 348 international students from China enrolled in the NZDipBus at UNITEC (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Chinese Students Enrolled in NZDipBus at UNITEC

4

New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research Volume 1, Number 1, 2002

R EASON FOR I NCREASE IN C HINESE S TUDENTS

Students from China study at tertiary educational institutes throughout the world. Out of the twenty-one countries reported in the Ministry of Education statistics, New Zealand ranked eleventh in the percentage of tertiary students who were not citizens of the country of study.

As of June 2000, Switzerland had close to 16% of tertiary students who are not citizens of the country, followed by Australia (more than 12%). New Zealand had less than 4% of the tertiary students who are not citizens of the country (Ministry of Education, 2001). Given the sharp increase of students from China, (Figure 2) New Zealand’s share is expected to increase in the near future.

Light (2001) suggests that the combination of increasing prosperity and lack of places in

Chinese universities has resulted in the number of Chinese students in New Zealand dramatically increasing. As there are 2000 applications to study in New Zealand going through the Foreign Affairs office in Beijing every month, she further estimates that the number could easily double in the next few years.

According to Grant Fuller, trade commissioner for Trade NZ in Shanghai, the average income in Shanghai is US$4,000 a year and graduates, with a degree and a few years’ experience, can easily earn US$25,000 a year (Light, 2001). This is perhaps another reason for Chinese students wanting to get an overseas qualification.

Ministry of Education, (2001)

Figure 2 Number of FFP Students in Public Tertiary Institutions By Countries of Origin in the Asia

Region

New Zealand is seen as a safe place to study. Tertiary institutions received increased inquiries from foreign students after the terrorism attacks on the United States in 2001

(Middlebrook, 2001).

After the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, NZ imposed quotas on the number of Chinese students allowed into NZ. These quotas were cancelled in October 1999. China has also

5

Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal endorsed New Zealand and Australia as acceptable education destinations (Gamble & Reid,

2002).

Cost is perhaps another main factor for Chinese students choosing New Zealand. A comparison of course fees and costs of living (Table 3) disclosed on educational websites showed that studying in the United States is the most expensive, 75% higher than New

Zealand. New Zealand is the cheapest among all the countries investigated.

UK USA Canada Australia NZ

Tuition

GBP

7,100

US$ C$ A$ NZ$

15,480 12,750 1 13,500 2

9,004 12,000 3 10,000 4 Cost of Living 6,000

Total 13,100 5 20,000 6 24,484 7 24,750 23,500

NZ$ equivalent 8 39,963 41,220 32,645 28,560

Cost higher than NZ 16,463 17,720 9,145 5,060

% over NZ 70.0% 75.4% 38.9% 21.5%

Table 3 – Comparison of Cost (Annual) of Study by Country

Apart from the cost element, the ease of obtaining a visa is an important consideration.

Although there is no mention on exactly how much is required as a condition for the issuance of the student visa, most countries require that the applicant should produce evidence to demonstrate that the student or the student’s family can readily afford the cost of an education on an ongoing basis. However, New Zealand Immigration only requires a completed “Financial Undertaking for a Student” or evidence of NZ$7,000 per year, and the provision for a return air ticket (New Zealand Immigration Service). Given the average income level in China, this comparatively lower requirement puts New Zealand in a favourable position to attract students.

E

NSURING THE SUCCESS OF

I

NTERNATIONAL STUDENTS

Kennedy & Dewar (1997) identified that EAL (English as an alternate language) students likely to succeed in NZ were those who:

had a good grasp of their first language and a good education in their home country, were exposed to ‘good’ language models and provided with plenty of opportunities to use their English, had an outgoing personality which gave them the confidence to speak with their teachers and their peers.

1

RMIT

2

UNITEC

3

Australia Immigration

4

Education NZ

5

University of Birmingham, UK

6

San Francisco State University (average figure between $19,000 to $22,000)

7

University of British Columbia, Canada

8

All foreign currencies are converted into NZ dollars at rates on 19 June 2002

6

New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research Volume 1, Number 1, 2002

Cummins (1994) in Carrasquillo and Rodriguez (1996) outlines the principles that affect the teaching-learning process of EAL students. The educational and personal experiences that the students bring to their new country are the foundation for their future study. As it can take up to five years for a student to become English language proficient there must be a long-term commitment provided to support the linguistic development of EAL students. In order to improve their English, EAL students must interact with English speaking people. EAL students must continue to grow academically as well as in their acquisition of language skills, therefore their acquisition of English language should occur at the same time as achievement of academic content. The interpretation of these principles into practice is that we cannot expect students to achieve at a higher level in a second language than they would have been capable of in their first language.

In a lecture, proficient English speakers will be concentrating on the cognitive task while

EAL students will be focussing on the linguistic as well as the cognitive task. Additionally

EAL students will be coping with different methodologies of teaching to that they have received in their home country (Carrasquillo & Rodriguez, 1996). Students in NZ are expected to initiate their own study i.e. we expect our students to be independent thinkers and not learn by rote what they have been told (Kennedy & Dewar, 1997).

Students from China are used to a teacher-centred environment, where the lecturers transfer knowledge step by step and explain everything in detail. Students have to listen quietly and speak only when they are called upon (Mak, 1996). Therefore, it is not uncommon for students to listen to the lecturer’s instruction most of the class time. Although Chinese students are used to a much heavier workload, e.g. more class instruction and a lot of exercises after classes, they are seldom required to do a presentation in front of the class or to write investigative reports. Liang (1990) and Mak (1996) both point out that in the Chinese education system there is very little opportunity for students to speak or be involved in class discussions. Liang (1990 ) also notes that Chinese students like to work together. This can cause problems in the New Zealand classroom where co-operative study is encouraged but collaborative work is viewed as mis-conduct and the students are penalised.

Given this background, coupled with the language barrier, Chinese students are seen in the

New Zealand classroom as unwilling to participate in group discussion and relatively weak in assignment work and oral presentations. These factors may have a negative impact on their academic achievement.

S URVEY R ESULTS

Seventy-nine students completed an anonymous questionnaire. The first group were Chinese students who were in at least their second semester at UNITEC (existing students). The second group were new students to UNITEC in their second week of study.

In both the new and existing student groups the majority of students were female and in the

20 to 24 age group (Table 4). The age distribution is consistent with Ministry of Education statistics. As at 31 July 2000, it reported that the largest group of students were in the 20 – 24 age group (Ministry of Education, 2001).

7

Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal

Demographics

New Students

Number of respondents

Age

<20

20-24

25-29

30+

Gender

Male

Female

Existing students

39

8

2

52

3

23

29

Table 4 – Demographics of Respondents

Total %

27 79

9

18

3 4%

18 57 72%

8 16 20%

1 3 4%

32

47

41%

59%

In the new entrant group the highest qualification earned by most of the students (35%) was high school graduation. In the existing student group 41% of the students had a university two-year diploma (Table 5). This result surprised us as the entry criteria for students (80% average in grade 3 high school) had not changed. However, it could be that we now have more Chinese students coming to study NZDipBus after completing high school in New

Zealand or because of the decreasing number of places available at Chinese universities.

High School

2 year diploma

3 year diploma

Bachelor

New students Existing students

18

12

10

1

35%

23%

19%

2%

3

11

7

1

11%

41%

26%

4%

Table 5 – Highest Qualifications before coming to UNITEC

Accounting, finance and management were the disciplines that most students had studied in their previous qualifications (Table 6). This was expected as we thought that students who had a tertiary qualification from another country would probably like to make use of that previous knowledge and experience when extending their qualification.

Accounting

Business

Finance

Int’l Trade

New students

5

5

Existing students

Accounting-computing

Accounting-management

Architecture

Engineering

English

Econ/hotel management

Total

1

1

12

Table 6 – Discipline of Previous Qualifications

1

1

1

2

1

20

10

2

2

8

New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research Volume 1, Number 1, 2002

Only the new intake students were asked their study plans after their first semester. 49% had already decided that they would continue with the NZDipBus, 14% were undecided and the remaining 37% had decided to transfer to the Bachelor of Business. This is the beginning of a new trend within the NZDipBus at UNITEC. In the past we have had large numbers of students who complete one or two semesters of the NZDipBus and then transfer to the BBus.

We attribute this to New Zealand immigration regulations that allow the same points value for a completed NZDipBus as for a Bachelor degree. (NZ Immigration Service)

The new entrant students were asked if they were considering applying for NZ residency on completion of their qualification and 74% said that they would.

Students were given a range of professions and countries to choose from when asked their plans after completing their qualification in New Zealand. They were also given the option of choosing more than one alternative. The results are summarised in Table 7. Most of the new students indicated that they would prefer to work in an English speaking country rather than return to China. However, there was an almost equal split between working in an English speaking country and returning to China amongst the existing students. This could have been a natural inclination to return home after being away for a period of time or the realisation that their qualification and proficiency in the English language would enable them to get a very good, high salary position in China.

Since becoming a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Chinese

Government now encourages overseas students to return home to meet the increasing demand for skilled professional. According to the Associate Minister of Education of China, Zhang

Cheng Xin, until 2001 there were over 140,000 overseas graduates who returned home, out of the 440,000 who had studied overseas in the last 22 years (Ha, 2002).

Work in NZ or other English

speaking country

New students Existing students

52

Return to work in China 21

Table 7 – Plans after Completion of Qualification

18

17

Students were given the option of indicating more than one reason for choosing to study in

New Zealand and given the opportunity of adding other reasons to the ones in the questionnaire (Table 8). Both groups ranked the top three reasons for coming to NZ to study as the opportunity to speak and study in English, the cheaper fees than other countries and the safety aspects of studying in New Zealand. Friends and family studying here, the advertising done in China and the ease of obtaining a visa were also significant reasons. Shen’s (1997) investigation into why Chinese FFP students attend NZ secondary schools showed similar reasons for students wishing to study in New Zealand. The value of a Western education in their own country and the safe environment with parents believing that their children would be less exposed to negative Western influences in NZ than in other Western countries were highly significant factors in her study.

9

Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal

To speak English

Safe

Cheaper fees

Easy to get visa

Well advertised

Relations here

Friends here

New students Existing students

39 21

35

24

12

19

18

11

11

7

10

7

4

2

Table 8 – Why Choose to Study in NZ/UNITEC

Most students found out about studying at UNITEC from educational agents in China (38%) while 28% were influenced by friends, 13% by trade shows and 13% by television advertising.

The existing student group was questioned just after the tragic events of September 11 2001.

We asked them if NZ was their first choice of place to study and there was an equal split of yes and no responses. Australia was the first choice for most students who had not initially chosen to come to NZ followed by UK and Canada. 10 of the 18 students answered NZ to the question “Because of recent world events what would be your first choice now?” Four of the eighteen decided that they wouldn’t leave home and answered “China” to this question.

The group of existing students were given an open ended question and asked to give their opinion of the best three features about studying in New Zealand and three reasons why they don’t like studying in New Zealand. (Table 9) The weather plus environment and the lower fees plus cost of living were considered by students to be the best reasons to study in New

Zealand, and the reason that most students didn’t like studying in NZ was because they found it too quiet or boring.

Best features about studying in NZ (students were asked to give 3 features)

First choice 2nd choice Third choice

Environment/weather

Lower fees/cost living

10

6

6

4

English speaking country

Safe

Quite/relaxing

Good learning environment

2

3

2

1

5

1

2

2

Location

Friendly people

Freedom

1

1 1

2

2

1

2

1

4

4

1

5

10

New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research Volume 1, Number 1, 2002

What don't you like about studying in NZ (students were asked to give 3 features)

Quiet/boring

First choice

7

Second choice

5

Third choice

To many Chinese 2

Business is small 2

Discrimination/unfriendly 1 1 1

Crime 1 1

Group assignments 1

Homesick 1 1

Lack of student activities 1 1

Lazy Nzers 1

Everything is old 1

Accommodation hassles

Poor economy

Communication problems

Large class sizes

1

1

1

1

Table 9 – What do you like and dislike about studying in NZ?

Speaking English, accommodation and socialising with native English speaking students were the main problems students associated with studying at UNITEC. (Table 10)

Speaking English

Accommodation

Socialising with Kiwis

New students Existing students

30 19

21

20

11

18

Food

Culture

1

1 1

Prejudice

Method of education

1

1

Homesick

Traffic jams 1

1

Table 10 – What problems have you encountered in NZ/UNITEC?

We knew that most students coming to study at UNITEC wanted to improve their English, and had problems associated with English as highlighted in the previous question. We also knew from anecdotal evidence gained from many years lecturing that students’ grades improved as their English improved. We therefore asked students how they had tried to improve their English. Watching TV, speaking with friends with whom English is the only common language, being in English-speaking study groups and studying English were the main methods students indicated in both groups (Table 11).

11

Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal

Watching TV

Friends with other languages

Studying English

English study group

Shopping

Travel in NZ

Clubs, church etc

Radio/singing

New students Existing students

38 25

36

27

12

15

18

15

14

11

1

Table 11 – How have you tried to improve your English ?

10

8

7

9

At UNITEC, with very high proportions of Mandarin speaking students in some classes, it is sometimes difficult to place students in groups with Kiwi students. Efforts are being made at

UNITEC to broaden the range of International students particularly into the South American market and through alliances with the National University of Samoa. These initiatives, while not increasing the number of first language English students, will provide a more diverse group of students for whom English is the only common language.

We were interested to find out from students how they thought that UNITEC could make their study better and more successful for them. Longer library opening hours, more language support and English classes, more handouts, smaller classes and better student accommodation were mentioned in significant numbers (Table 12).

Library open longer

More language support

More handouts

More English classes

Smaller classes

Better accommodation student

Simpler words

Different cultures together

Everyone speak English in class

Computer labs open longer

24

18

16

13

12

11

2

2

2

1

Table 12 – How UNITEC could make your study more successful

The request for longer library opening hours was explained by one of the students in the focus group. He said that it was very difficult to study in student accommodation or in homestays. The UNITEC library is open seven days a week and has extended weekend opening hours during exam times.

12

New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research Volume 1, Number 1, 2002

S UMMARY

The New Zealand environment, cheaper cost, the ease of obtaining a visa and New Zealand seen as a safe place are the main reasons expressed by the respondents of our survey as to why they chose to come to New Zealand.

On the other hand, respondents also felt New Zealand was boring and quiet compared to their home country where the population figure is much higher. Language barriers created major problem in their study as well as their daily life. Being new to the place and lack of social life contributed to their loneliness. They also experienced difficulty in finding suitable accommodation.

These findings are consistent with the observations in our literature review.

W HAT UNITEC HAS DONE

At UNITEC we have recognised that having high numbers of students who do not have

English as a first language places an added strain on lecturing staff. Various initiatives have been undertaken within the Schools that teach the NZDipBus programme.

Staff Training

A number of staff training days have focussed on giving academic staff the opportunities to discuss common areas of concern and to share best practice. Specialist EAL lecturers have facilitated workshops aimed at providing lecturing staff with skills to enhance their teaching practice. Staff have been encouraged to enrol in the Graduate Diploma in Higher Education programme and in particular the Multicultural Teaching course. Some staff have completed

Mandarin speaking classes and most staff have attended workshops where they have been taught to pronounce Chinese names and basic greetings.

Staff have been made aware of the educational methods Chinese students have previously been exposed to and given advice as to how to make students more involved in their learning.

The UNITEC Learning Support EAL specialist has volunteered to critique all assessment items for lecturers for misleading language elements. This offer has been accepted by many staff.

Student Support

The English language entry criteria for the NZDipBus at UNITEC is Academic IELTS 6.0.

For many years a separate stream (EAL stream) has been offered for students with an

Academic IELTS of 5.5. These students study two courses in their first semester (rather than the standard three papers) and receive extra class contact hours. In Semester 1 2002 a “home room” class was offered to the EAL streams. Once a week the NZDipBus Programme Leader organised for academic support staff from within UNITEC to work with the students. For example, one of the librarians assisted the students by showing them how to navigate the library, physically and on the library databases. She also helped the students by giving them tips on how to search library databases and other search engines. A lecturer from Te Tari

13

Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal

Awhina (the UNITEC learning support centre) facilitated many very useful sessions. Early in the semester she assisted them by talking about the different ways of learning in a New

Zealand teaching environment and the importance of asking questions and participating in activities in class. She spent time with the students on group work, how to take notes and how to structure different types of assignments. Later in the semester she held very useful sessions on how to study for exams and tips for the exam room. These “home room” sessions were optional for students and held on a Friday afternoon but were very well attended.

All students at UNITEC have access to Te Tari Awhina who offer academic skills and course content workshops, small group or one-on-one tuition. Their specialist accounting and business maths tutors are very popular with NZDipBus students.

In addition to academic staff office hours, all students enrolled in the NZDipBus have access to clinics for core papers. These clinics are run for two hours, once a week and offer to students one-on-one or small group tuition. Until Semester 2 2002 these clinics were run by senior students. Some of these senior students were native Mandarin or Cantonese speakers.

From Semester 2 2002 part-time lecturing staff will facilitate these clinics.

In the NZDipBus at UNITEC we are committed to small class sizes for EAL and

International streams. We recognise the pressures that students and lecturers are under when they do not have a common first language. Therefore class sizes for these steams are kept to a maximum of 30. The smaller class size is designed to encourage students to be more interactive with their peers and the lecturer.

Students who do not have English as a first language appreciate being able to pre-read lecture material. At UNITEC we make extensive use of the Internet based BlackBoard course management tool and students are encouraged to access lesson plans, handouts, powerpoint slides and additional readings provided on BlackBoard.

Future plans

The students accepted into the NZDipBus at UNITEC have the required English language ability (IELTS 6.0) and the appropriate educational level from China. However, very many of them still struggle with academic study. In recognition of this a more formal approach to providing them with academic skills is being investigated. Following on from the success of the “home room” initiative a suggestion has been made that all students are required to do a series of workshops covering topics such as how to study in New Zealand, how to research and write assignments, how to become involved in group work, how to do presentations, how to study for and write examinations and general classroom conduct covering techniques as to how to be involved and ask questions. We are aware that workshops such as these could not form part of an NZDipBus course and are looking at ways of incorporating them into the students’ study outside the NZDipBus framework.

14

New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research Volume 1, Number 1, 2002

W HAT ELSE SHOULD BE DONE !

9

Export education is now one of the main income earners for New Zealand. This trend is likely to continue. At UNITEC, student numbers from China are expected to grow in the years ahead, as a result of the NZ DipBus programme being offered at UNITEC Fanzhidu in

Beijing. Students who are successful in these courses can transfer to the NZDipBus at

UNITEC or gain cross-credits to the Bachelor of Business programme. However, according to Lester Taylor, chief executive of Education New Zealand, we cannot sustain the level of growth we have had without some re-thinking about the services we provide for students who come here (Cumming, 2002).

To maintain the reputation that New Zealand is a good education destination, both the education providers and the Government should look for ways to provide solution to problems faced by international students. We consider the implementation of the following is essential.

Language Support

Language support is seen as key to help international students whose first language is not

English succeed academically. The sooner they are able to communicate in English effectively, the easier it will be for them to mix with local people and to adapt to the New

Zealand environment. Extra English classes, especially for those newly arrived, will be of great help to them to adapt to the new environment.

Accommodation

Problems in finding suitable accommodation are not uncommon for many international students. Education providers should expand student hostels so as to allow more students to have access to this service. Or alternatively, they may consider providing assistance to students who have problems in locating suitable accommodation. A person whose job is to locate suitable homestay hosts for those students who have registered their interests with the institutes to which they belong could be appointed.

Student Counsellor

Education providers should have a student counsellor who can speak their language (i.e.

Mandarin and Cantonese) to help international students. To overcome the issue of “boring” and “quiet”, the student counsellor could also arrange social events jointly with the student union from time to time where the international students can mix and mingle with Kiwi students.

9

This paper was written before the Code of Practice for the Pastoral Care of International

Students was introduced.

15

Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal

Student Centre

International student centres should be set up in major town centres (similar to the Tourist

Information Centre). This will provide the students with an avenue to seek for information and to lodge complaints that cannot be appropriately channelled through their own institutes.

The Government should allocate resources to fund the set-up of these centres, as well as the cost of implementing any of the above initiatives by the educational providers. This may come from the 1% levy on tuition fee that the Government propose to collect from education providers effective next January.

F URTHER S TUDY

Throughout our study, we found other issues associated with international students, and students from Asia in particular. Statistics New Zealand figures for last year show that abortions accounted for 364 of every 1,000 known Asian pregnancies, a rate about 61 per cent above the national average (Editorial, NZ Herald, 14 June 2002). Scarcity of sex education is suggested as the main reason for this.

According to Nadia Chen, the chairwoman of the Hakka Society of New Zealand, unprotected sex was a particular problem with students from mainland China, as the country was conservative and there was little sex education. She also pointed out that many started intimate relationships due to loneliness and a need for support (Gregory, 2002).

MacKay (2002) suggests that educational institutions need to take responsibility for providing sex education, if the “burgeoning” Asian student abortion rate is to be slowed.

In our study, respondents expressed “boring” and “quiet” as the key factors they dislike about studying in New Zealand. It is not difficult to understand that many students feel lonely because they are so far away from home and from their own social circles.

One of the main reasons for international students to come here is to learn English. With the increasing number of Chinese students in our classroom, they may not be able to learn

English in the way they prefer. Yu Xin Wu, 21, from Canton, China is quoted as saying “It feels like being in an Asian city. It’s good for us to overcome the culture shock but not good to learn English” (Cumming, 2002). This highlights the problem of having high numbers of

Chinese students in our classroom.

We suggest that further research be carried out. The research should address issues not covered by the current research, such as how to reduce the high student abortion rate, whether sex education should be provided, as well as what should we do to maintain an appropriate balance of student mix in our classroom.

16

New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research Volume 1, Number 1, 2002

R EFERENCES

Australian Immigration. available URL: http://www.immi.gov.au/students/assessment.htm

Carrasquillo, A., Rodríguez,V. (1996). Language minority students in the mainstream classroom. Multilingual

Matters Ltd. Clevedon.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. available URL: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/visit/study_e.html

Cumming, G. (1 June 2002), Mean hosts jeopardise a billion-dollar industry.

New Zealand Herald.

Education New Zealand . available URL: http://www.nzeil.co.nz/additional_info/livcost.htm

Education New Zealand Trust. (2002). Handbook of Courses and Costs 11 th Edition.

Evans, S. (2002, May 29). Cash cows or not?

Education Review.

Gamble, W., Reid, G. (May 18, 2002) Lessons in foreign exchange. Weekend Herald.

Gregory, A. (12 June 2002) Abortion rate for Asians high. New Zealand Herald.

Ha, B. (14 January 2002), Overseas graduates return home for good.

Volume 3, Issue 16, Yazhou Zhoukan,

The International Chinese Newsweekly.

Kennedy, S., Dewar, S. (1997). Non-English speaking background students: A study of programmes and support in New Zealand schools . Ministry of Education. Wellington.

Liang, Z. (1990) A Survey on Chinese Students in Auckland University. Thesis (MA-Education), University of

Auckland.

Light, L. (19 October 2001), Nurturing the golden goose, New Zealand Education Review.

MacKay, P. (3 April 2002), Asian abortions rocket. New Zealand Herald.

Maharey, S. (12 October 2001) NZ Inc is best way forward handling huge Asian education opportunities. The

National Business Review.

Mak, B.S.Y. (1996) Communication Apprehension of Chinese ESL Students.

Master Thesis – Arts, Massey

University.

Middlebrook, L. (18 October 2001) Foreign students view NZ as safe destination. New Zealand Herald.

Ministry of Education (June 2002), Number of students enrolled in formal programmes of study at Tertiary

Education Providers at 31 July 2001. Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (June 2001), Foreign Fee-Paying Students in New Zealand – Trends, A Statistical

Overview . Prepared for the Export Education Policy Project, Strategic Information Resourcing Division,

New Zealand Ministry of Education.

New Zealand Herald Editorial, (14 June 2002) Overseas students need care. New Zealand Herald.

New Zealand Immigration Service. available URL: http://www.immigration.govt.nz/visit/need.html

RMIT. available URL: http://www.international.rmit.edu.au/is/MELBOURN2.htm

San Francisco State University. available URL: http://www.sfsu.edu/prospect/intl.htm

Shen, C. (1997) Opening Doors, Opening Minds: The Perceptions and Experiences of Chinese Full Fee Paying

Students in Selected Auckland Secondary Schools. Thesis (Mphil-Education) University of Auckland.

17

Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal

University of Birmingham, UK. available URL: http://www.ao.bham.ac.uk/dalia/tuition.htm

University of British Columbia, Canada. available URL: http://students.ubc.ca/welcome/costs/firstyear.cfm

UNITEC Institute of Technology. available URL: http://www.unitec.ac.nz/index.cfm?83BF53B2-BC62-4862-

B81A-OEC9D7D94C25

Note: All information from websites is valid as of 26 June 2002.

18