Prevalence of Academic Dishonesty in Tertiary Institutions: The New Zealand Story A

advertisement

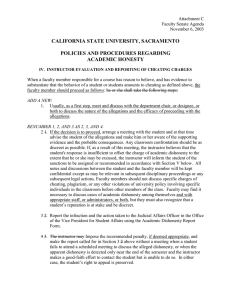

Prevalence of Academic Dishonesty in Tertiary Institutions: The New Zealand Story Kelly de Lambert, Nicky Ellen, Louise Taylor School of Business, Christchurch College of Education ABSTRACT This paper presents the findings of an investigation into the prevalence of academic dishonesty in New Zealand’s tertiary institutions and compares this with findings from other studies. Three separate surveys were administered in order to examine the issues from a range of perspectives. Staff and students report on their personal experiences of academic dishonesty and these are compared with official information requested and supplied by the institutions. Finally the study examines methods academic staff can adopt to minimise the occurrence of dishonest behaviour. INTRODUCTION The research undertaken is primarily concerned with the tertiary sector in New Zealand, specifically universities and polytechnics, and encompasses a variety of academic disciplines. Although there is a comprehensive set of studies available from overseas, there is very little material available in the New Zealand context. To this end, an independent study was carried out with New Zealand tertiary institutions, students and academic staff. Areas investigated include prevalence, perceptions, justifications, action and non-action, penalties, policy and prevention. The intention of this conference paper is to present the findings from two of these areas - prevalence and prevention in order to both inform New Zealand practitioners of the situation in this country and to provide practical methods of minimising the opportunities for academic dishonesty within the tertiary environment. Throughout this paper the term academic honesty is used to describe the submission of work for assessment that has been produced legitimately by the student who will be awarded the grade, and which demonstrates the student's knowledge and understanding of the content or processes being assessed. Evidence to support the student's work can, and should, be provided by referencing legitimate work of others, as long as it is appropriately acknowledged. Therefore, academic dishonesty includes any behaviour that breaches this. As the study was investigative in nature, statistics presented in this paper are descriptive rather than inferential. LITERATURE REVIEW A literature search was undertaken from which a number of major studies in the area of academic dishonesty at tertiary level were identified. These studies were based primarily in universities in the United States of America and Great Britain. A variety of techniques were used for data collection in these studies, including questionnaires and interviews, both structured and unstructured. Roig and Ballew (1994) report on various studies undertaken into the prevalence of academic dishonesty, including a major study carried out by Davis, Grover, Becker and McGregor in 1992 where it was found that 76% of the students surveyed reported cheating in high school or college. This is borne out by Payne and Nantz (1994) who report that between 67% and 86% of university students are involved in some form of academic dishonesty. Payne and Nantz's study involved in-depth interviews with 22 university students, 19 of whom admitted cheating of some sort in their tertiary career, compared with another study carried out at the same university where it was shown that 60% of male students and 55% of female students indicated acting dishonestly. Literature on comparisons of prevalence between ethnic groups is sparse. However, a study to investigate attitudes and tendencies of United States university students versus Central European (Polish) students was carried out in 2000 and concluded that a much greater proportion of Polish students had been involved in some form of cheating (84%) during their tertiary career than their counterparts from the States (55%) (Lupton, Chapman, & Weiss, 2000). Research by Genereux and McLeod (1995) suggests vigilance (when proctoring exams) and fairness of assessments are the largest deterrent for academic dishonesty. Pulvers and Diekhoff (1999) believe the strongest deterrent is embarrassment and other negative social consequences. One form of prevention discussed in the literature suggests institutions with traditional academic honour codes have a much lower incidence of academic dishonesty, especially when students are involved in the process of establishing the code as they tend to identify more with their institution and this then leads to lower rates of cheating (McCabe, 1999; Kibler, 1992; Fishbein, 1993). Students who are beyond their own competence (often internationals) cheat to survive and therefore institutions should develop careful recruiting procedures, allowing students only within their band of ability. They should also institute first year writing classes emphasising plagiarism definitions, appropriate referencing, as well as including defining of academic responsibility and expected code of conduct (Simon, Carr, De Flyer, McCullough, Morgan, Oleson & Ressel, 2001). McCabe, Trevino and Butterfield (2001) believe that increasing the opportunity to peer report increases students’ beliefs that the chance of getting caught is higher. Studies completed by McCabe (1993) indicate increased penalties act as a deterrent. METHOD Three questionnaires were developed and administered to the following groups of people: Academic institutions – questionnaires were sent to the Registrars of all New Zealand polytechnics and universities (22). The purpose of the questionnaire was to determine the number of 2 equivalent full-time students attending, the number of documented cases of dishonest practice and the sanctions imposed. Information was requested under the Official Information Act 1982 and care was taken to ensure that institutions understood that their responses would be kept confidential. The 14 institutions whose responses were received host 194,594 of New Zealand’s 282,808 tertiary students (2001 data). With an average EFTS (Equivalent Full-Time Student) population of 6,086, the responding institutions were at the larger end of the scale, educating between 1,000 and 15,000 students each. Academic teaching staff – questionnaires were piloted and then posted to 350 lecturing staff, representing a range of disciplines in polytechnics and universities throughout New Zealand. Staff were selected at random from web sites and calendars of all polytechnics and universities. The questionnaires were five pages in length and requested detailed information about the respondent’s views on a range of given scenarios including severity of the action, suitable penalties, frequency of behaviour, their actual experience of the dishonest act, and the actions they took. They were also asked to report on reasons for any lack of action on their part, justifications provided by students for dishonest practice, methods used to try to reduce future instances of dishonest practice, and their views on the effectiveness of their institution’s academic dishonesty policies. Respondents were also asked to provide some demographic details to allow for cross matching of data. Because of the lengthy nature of the questionnaire and the sensitive nature of some of the content, small inducements were provided for completion, consent forms were requested and a covering letter reassuring confidentiality were sent with the questionnaire. The statistics from the Ministry of Education indicate a mix of 55.3% male versus 44.7% female academic staff in polytechnics and universities in New Zealand to July 2001. This compares with the responses obtained for this survey of 63.4% male and 36.7% female. Ages last reported by the Ministry of Education from the 1996 census compare relatively well with the sample. Staff surveyed also spanned a range of qualifications taught and correlated well to the sample of students studying the same qualifications (8.8% at certificate level, 13.3% at diploma level, 69.0% at bachelor’s degree, 8.9% post-graduate qualification). Tertiary students – questionnaires were piloted and then 380 administered with students at two universities and one polytechnic. Students were approached at the campus cafeterias during the lunch hour and asked to participate in the survey. The questions were similar to those asked of academic teaching staff, but were related to the student’s own experience and perceptions of academic dishonesty and included questions about the likelihood of them reporting a fellow student who they suspected of cheating. As with the academic staff questionnaire, small inducements were provided, and assurance given as to the confidential nature of the responses. The student sample was representative of the student population of New Zealand polytechnics and universities, as provided by the Ministry of Education in their student statistics across the tertiary sector to 31 July 2001. Just over half of the students (50.7%) sampled were female (2001). Ages of students sampled were broadly 3 representative with the exception of the over-40 category – Ministry of Education statistics indicate this category represents 18.1% of all tertiary students, whereas the current sample captured only 1.6% of students in this range (2001). The sample included students from a range of academic disciplines including Commerce, Humanities, Science, Engineering, Law and Trades. All subject areas were represented but variations from Ministry of Education statistics occur, eg an over-representation in the field of Commerce (13.4% variance) and an under-representation in the field of Humanities (11.8% variance). All other areas were within 5.0% (2001). Students sampled were studying for a range of qualifications (10% at certificate level, 10.4% at diploma level, 75.8% at bachelor’s degree level, 3.7% at post-graduate level). A high proportion (93.4%) of the students surveyed were studying on a fulltime basis, which more accurately represents the time of day at which the survey was administered (mid-day) than the general student population, which is much more evenly divided between full and part-time students. The sample also included a wide range of ethnicities from throughout Asia, Europe, North America, Africa and the South Pacific. Response to the survey instruments was favourable; the surveys posted to academic institutions and academic staff generated response rates of 46.6% (14 responses received) and 32.3% (113 responses received - 96 university staff and 17 polytechnic staff) respectively. 380 students took part in the survey (257 university students and 122 polytechnic students). Interest in the survey was remarkably high. Of the students approached, very few were not prepared to complete the questionnaire, with some students proactively asking to take part. Academic staff responses indicated a willingness to participate, with some excellent comments and personal experiences added to the questionnaires. At the outset of the research project, we identified a range of different dishonest practice examples and considered their seriousness. The questionnaires used with both students and academic staff listed 22 examples, and also included some which we viewed as not examples of dishonest practice, to provide some integrity to the survey process. It was clear when analysing the data that one of the examples provided was ambiguous. The example was “gaining access to test material before sitting it”. We had intended this to mean actually seeing the test or marking schedule prior to the test, but it could have been interpreted as getting access to legitimate resources such as case studies given out before the test. Because of the ambiguity, the results for that example were removed from the data. Table 1 classifies the remaining 21 examples as Serious Cheating, Minor Cheating or Not Cheating on the basis of consensus between us. These examples, and specifically those numbered 118, will be referred to throughout the article. This classification is subjective, representing our own personal views. 4 RESULTS Prevalence Institutions reported that a total of 342 allegations of academic dishonesty had been made in the 2001 academic year, 338 of which originated from staff and the remainder from students. In summary, allegations of dishonest practice were made against .2% of the student population in surveyed institutions. Both students and staff were asked to report on their actual experience of the various types of academic dishonesty. From the listed examples, students indicated any that they had engaged in during their tertiary career; staff indicated which of the list they had experienced with any of their students in their tertiary teaching career. Responses are outlined in Table 2. Of particular note is the high incidence of dishonesty involving information technologies and lack of referencing. Close to 80.0% of staff indicated some experience of students either paraphrasing or copying directly from a web site, book or periodical without referencing the source – we viewed both scenarios as serious. Students also indicated lack of referencing as the most common form of serious dishonest behaviour. Of the minor cheating offences, continuing to write after a test had finished was the most common offence committed by students – 51.3% of students admitted engaging in this form of dishonest practice. Staff also reported a high incidence of their experience of this, with more than three quarters reporting experience of students writing after a test has finished. An extraordinarily high proportion of staff (95.6%) had experienced dishonest practice in any of the listed forms during their tertiary teaching career; 94.7% indicated at least one serious incident, and 91.2% indicated at least one minor incident. Of the students surveyed, 80.3% reported they had engaged in any of the listed offences; 63.4% indicated at least one serious incident, and 74.7% indicated at least one minor incident. It must be borne in mind that these figures are not directly comparable as the length of a tertiary teaching career is likely to be greater than the length of a student’s tertiary learning career. Nor does it reflect the magnitude of any individual listed offences. In an effort to further delineate the group of students who had admitted some form of dishonest practice, to search for trends, the information was cross referenced with students’ reporting of the subject area in which they were currently majoring. The sample consisted of 137 Commerce students, 74 Humanities students, 107 Science students, 30 English students, 5 Law students and 19 students undertaking trade training. Figure 1 shows that the results were reasonably evenly distributed across the subject groups with the exception of the Law students who admitted the largest number of incidents of dishonest practice in nine of the 18 examples used and were highest equal in one other. This information must be interpreted in the context of the sample, however; as the number of Law students sampled was very small, the results may well be unrepresentative. 5 Students were asked to indicate the ethnicity with which they relate. This was later compared with students’ self-reported histories of academic dishonesty during their tertiary career. For ease of analysis, data were grouped into the only three categories of a sufficient size to allow meaningful analysis - Asian (54), European (37) and New Zealand, including Maori and Pakeha (274). Figure 2 depicts the number of students (as a percentage) from each of the three ethnic categories who reported that they had, on at least one occasion during their tertiary career, engaged in the behaviour described in the scenario. The results do not appear to vary significantly between ethnic groups. While some forms of academic dishonesty are more popular with one particular ethnic group, when averaged across all of the examples, these differences are minimal. As depicted in Figure 3, the group of students least likely to admit having previously engaged in incidents of dishonest practice were those aged 30 years and over. This group made up the smallest proportion in 14 of the 18 listed examples. This information should, however, be interpreted in light of the demographic distribution of the sample in that older students were significantly under-represented. The sample included only 35 students in this age range. The overall difference between students aged under 20 and those aged 20-29 was minimal when averaged across all of the examples. Although there were idiosyncratic differences in each of the different examples, these did not form a notable trend. We were interested to further analyse the student responses on the basis of gender and, as Figure 4 depicts, this showed a clear trend with males leading females in each of the 18 categories of dishonest practice, although the differences are small for some types of offence. It is interesting to note that the largest differences between the gender categories occurred in the more serious examples of dishonest practice (categorised by us as numbers 1-13). The groups were more congruent in the minor examples. Staff who had taught for five years or more were asked to comment on whether they thought incidents of academic dishonesty among students over the past five years had increased, decreased or remained stable. 51.5% of respondents thought that incidents had increased, with 20.6% believing the increase had been significant. 46.4% of respondents believed the level of dishonest practice among students had remained stable and 2.1% believed it had decreased slightly. No respondents believed that dishonest practice had decreased significantly during this time. Both students and staff were asked to estimate the number of students they believe engage in each of the given forms of dishonest practice. In general, both students and staff believed that 0-9% of students commit serious cheating offences. Views between the groups differed, however, with regard to minor cheating; staff believed that 0-9% of students commit these types of offences while students estimated the figure to be 25-49%. 6 Prevention Thirteen methods for minimising the chances of academic dishonesty occurring through assessments were provided in the academic staff questionnaire. Respondents were asked to indicate which, if any, of the methods they had adopted in an effort to prevent the occurrence of dishonest academic practice in their classes. Table 3 presents, in descending order of frequency, the results of this question and indicates that other than discussing cheating and academic dishonesty openly and strongly with students, staff themselves appear to adopt few strategies to minimise dishonest practice in their classes. Honour codes, discussed in overseas literature and administered mainly by students themselves, are virtually unheard of in the New Zealand education context and only 8% of staff indicated they institute something similar in their classes. DISCUSSION We were astounded at the high level of prevalence of both serious and minor acts of dishonest behaviour reported by staff and students in New Zealand tertiary institutions. It was of little comfort to discover that we compare closely with our overseas counterparts. The statistics gathered from our surveys of staff and students, however, were not borne out by the remarkably low level of reported instances at institution level. This could indicate that policies are not well established or enforced, that academic staff are dealing with incidents as they occur, that management fear legal reprisals, or could it be that acts of academic dishonesty are being ignored? Much of the dishonest practice occurring, both in New Zealand and overseas, involves falsification of research, lack of referencing and prohibited collaboration. This indicates a need for clear guidelines and increased education in this area. Students need to be made aware of what constitutes academic dishonesty, and these rules need to be applied consistently throughout the institution. Our questionnaires concentrated on what individual staff are currently doing to prevent or minimise dishonest practice. The literature provided other examples of actions being taken by academic staff and of course there is much that institutions and indeed students themselves can do. Using plagiarism detection software (and advising students that it is used) such as turnitin.com or plagiarism.org were mentioned by two staff members as prevention (and detection) strategies used. (Free plagiarism detection software is available at http://plagiarism.phys.virginia.edu). Even typing a well written, unique phrase into google.com can find plagiarised material in a few seconds, without having to pay for costly plagiarism detection software. Staff also need to provide clear guidelines for assessments, including referencing expectations. Unauthorised collaboration and limitations about submitting the same work for two courses need to be clearly explained on all assignments or in course 7 outlines. Staff need to investigate their own assessment practices, as students seem to resort to inappropriate means when they believe assessments contain unsuitable questions, are too much work or assess what has not been taught. Other more obvious prevention methods include closely proctoring exams, checking for ID, scrambling test questions, including more essay type questions, or assigning seating. Some surveyed staff offered suggestions to minimise plagiarism including informing students that they may be called into the lecturer's office to discuss the content of written assignments, or collecting notes and rough drafts along with finished essays; both acting as confirmation of originality, and therefore deterrents. Institutions need to clearly outline, in a policy, definitions of actions and behaviours which constitute cheating, how punishments are administered and communicate this to both staff and students in as many forms as possible. Any institutional policy needs to include a viable system for detection which will increase numbers caught, for example investing electronic detection methods such as internet search aids for plagiarism detection. Students need to be involved in development and promotion of academic dishonesty within the institution as increasing student participation in the decision-making process and general campus life may reduce academic dishonesty. Responsibility for academic integrity should be given to a small number of people, who receive training, and act as coordinators for prevention of cheating, and who also may assess the effectiveness of policies and procedures and promote academic integrity within the institution. Having a central person or persons would restrict students’ ability to negotiate privately with staff members, except in only the most minor offences. Institutions, and departments within institutions, need to provide guidelines on course development and administration processes that minimise the potential for cheating. Examples include examination procedures such as assigned seating in exams, limited multi choice, limited recycling of past assignments, shredding early editions and encouraging printing by students only when essential. Training should be provided for faculty members on assessment methodologies which limit academic dishonesty, and ways to deal with alleged cases. Advice should be given to students, encouraging them to take responsibility for minimising the attraction of acting dishonestly during their academic careers. Such advice could include: Training in time management and note taking skills. Reinforcing to students that they should ask questions to clarify the institution's policies and procedures as well as what is expected with regard to reference lists and documenting sources. Encouraging students to seek feedback on their progress. Explaining to students the help that is available and showing them how to access it. Discussing means of identifying stresses and ways to deal with them. 8 LIMITATIONS The findings from this study are limited in application and generalisability because of restrictions in the sample size and sample constitution. In particular, many more university staff responded to the survey than polytechnic staff and, while the sample size was reasonable, a larger range of respondents would have enhanced the study. It is possible that both the staff and student samples were distorted. Because participation was elicited voluntarily, participation may have been more attractive to those with a particular interest in the area and results may, for this reason, be distorted. Comparisons between staff and student data can be made only in view of the composition of the relative samples; in particular students from only three Canterbury institutions were surveyed whereas staff surveys were sent to staff at a range of tertiary institutions throughout the country. Although staff and students were asked to report their experiences over the course of their tertiary career (teaching career in the case of the former and learning career in the case of the latter), the tertiary teaching career of staff is likely to be greater than the tertiary learning career of students, thus reducing the comparability of the findings between the groups. Although steps were taken to assure participants that their anonymity would be protected, the information requested was sensitive and some participants may have distorted their responses. Additionally, the surveys for staff and students took respondents 15–25 minutes to complete, potentially leading to fatigue in some respondents with its attendant risks. The scale provided to respondents to estimate the prevalence of each of the listed types of dishonest practice included a 0-9% category (the most common category selected by respondents) However, it would have allowed more informed distinction if a category of 0% had been separately provided as well as a 1-9% category because, in this instance, 0% (indicating that the behaviour does not exist at all), is qualitatively different from 1%. The survey instrument was not sufficiently sensitive to measure some aspects of the topic which, in hindsight would have been interesting. For example both staff and student surveyed asked respondents to indicate whether they had encountered or engaged in each of the listed examples of dishonest practice; it did not, however, take account of the number of times the respondents had encountered or engaged in the conduct. This may have identified some important distinctions. Cross analysis of some of the collected data against this criteria would have been interesting. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION Academic staff report high incidents of their students cheating and students themselves admit their own dishonesty. However, the number of reported incidents of academic dishonesty at 9 institutional level does not support this. Demographics appear to have varying effect on prevalence, a higher percentage of males admit acting dishonestly than females in every category, students in the under-30 years age group are more likely to act dishonestly, whilst this study presented few conclusions in terms of ethnicity or academic discipline. As academic teaching staff, an area of particular concern is the high incidence of infringements surrounding research, such as falsification of results, copying the work of others and a lack of referencing. Clearly students are unaware of their obligations and the serious nature of these particular examples. The most common method used for minimising academic dishonesty appears to be education of students within the classroom. This does not seem to have been very effective in terms of the researching and referencing infringements, however. Responsibility for minimising the incidence of academic dishonesty falls on all stakeholders within the tertiary institution. Institutional management need to establish appropriate policies and procedures for minimisation, detection, enforcement and sanctions to be imposed. Once established, these policies must be communicated widely, strictly adhered to and evaluated. Academic staff could use a range of techniques for detecting academic dishonesty including plagiarism software, more vigilant exam supervision techniques, contracts with students, but clearly need to be more overt in the education and advice provided to students about what constitutes academic dishonesty, and what is expected. Students themselves also need to take responsibility for their actions and seek help and support as required. It is clear from our study that academic dishonesty, both serious and minor, is rife in New Zealand tertiary institutions, as it is overseas, but there are ways of minimising the risks. 10 TABLES AND FIGURES 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Serious Cheating: Copying from another student during a test. One student allowing another to copy from them in a test. Taking unauthorised material into a test – notes, pre-programmed calculator, etc. Giving answers to another student by signals. Receiving answers from another student by signals. Getting someone else to pretend they are the student – impersonating the student in a test. Paraphrasing information from a web site, book or periodical without referencing the source. Copying information directly from a web site, book or periodical without referencing the source. Copying information directly from another student (current or past) without their consent. Paying another person to complete an assignment. Falsifying the results of one’s research. One student allowing another student to copy their assignment. Writing an assignment for someone else. 17 18 Minor Cheating: Continuing to write after a test has finished. Padding out a bibliography with references that were not actually used. Copying information directly from a web site, book or periodical with reference to the source but no quotation marks. Collaborating on an assignment when it should be individual. Preventing other students from accessing resources required to complete an assignment. 19 20 21 Not Cheating: Using old test papers or other institutions’ course notes for study purposes. Studying from notes written by someone else. Using study techniques to aid memory. 14 15 16 Table 1: Seriousness of Cheating (Researchers' Opinions) 11 Student Reporting of Actual Occurrences Staff Reporting of Actual Occurrences Serious Cheating: 1 Copying from another student during a test. 16.8% 38.9% 2 One student allowing another to copy from them in a test. 15.3% 26.5% 3 Taking unauthorised material into a test – notes, pre-programmed calculator, etc. 9.2% 41.6% 4 Giving answers to another student by signals. 9.5% 8.0% 5 Receiving answers from another student by signals. 7.9% 8.0% 6 Getting someone else to pretend they are the student – impersonating the student in a test. 2.6% 2.7% 7 Paraphrasing information from a web site, book or periodical without referencing the source. 42.1% 77.9% 8 Copying information directly from a web site, book or periodical without referencing the source. 25.8% 78.8% 9 Copying information directly from another student (current or past) without their consent. 6.8% 41.6% 10 Paying another person to complete an assignment. 3.9% 9.7% 11 Falsifying the results of one’s research. 20.5% 14.2% 12 One student allowing another student to copy their assignment. 34.7% 60.2% 13 Writing an assignment for someone else. 8.9% 13.3% Minor Cheating: 14 Continuing to write after a test has finished. 51.3% 76.1% 15 Padding out a bibliography with references that were not actually used. 38.4% 63.7% 16 Copying information directly from a web site, book or periodical with reference to the source but no quotation marks. 36.8% 77.9% 17 Collaborating on an assignment when it should be individual. 46.6% 61.1% 18 Preventing other students from accessing resources required to complete an assignment. 7.4% 18.6% Table 2: History of Actual Occurrences 12 Researchers' Serious Cheating: 1 Copying from another student in a test. 2 One student allowing another to copy from them in a test. 3 Taking unauthorised material into a test. 4 Giving answers to another by signals. 5 Receiving answers from another by signals. 6 Impersonating a student in a test. 7 Paraphrasing without referencing. 8 Copying published information without referencing. 9 Copying information from another student without consent. 10 Paying another to complete an assignment. 11 Falsifying the results of one's research. 12 One student allowing another to copy their assignment. 13 Writing an assignment for someone else. Researchers' Minor Cheating: 14 Continuing to write after a test has ended. 15 Padding out a bibliography with references that were not actually used. 16 Copying information with reference to source but no quote marks. 17 Collaborating on an individual assignment. 18 Preventing others from accessing resources needed for an assignment. Percentage of Respondents 100.0 80.0 60.0 40.0 20.0 0.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Types of Offence Co mmerce Humanities Science Engineering Law Trades Figure 1: Actual Offences Admitted by Students (by Faculty) Percentage of Respondents 100.0 80.0 60.0 40.0 20.0 0.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Types of Offence A sian Euro pean New Zealand 17 18 Researchers' Serious Cheating: 1 Copying from another student in a test. 2 One student allowing another to copy from them in a test. 3 Taking unauthorised material into a test. 4 Giving answers to another by signals. 5 Receiving answers from another by signals. 6 Impersonating a student in a test. 7 Paraphrasing without referencing. 8 Copying published information without referencing. 9 Copying information from another student without consent. 10 Paying another to complete an assignment. 11 Falsifying the results of one's research. 12 One student allowing another to copy their assignment. 13 Writing an assignment for someone else. Researchers' Minor Cheating: 14 Continuing to write after a test has ended. 15 Padding out a bibliography with references that were not actually used. 16 Copying information with reference to source but no quote marks. 17 Collaborating on an individual assignment. 18 Preventing others from accessing resources needed for an assignment. Figure 2: Actual Offences Admitted by Students (by Ethnicity) 13 Percentage of Respondents 100.0 80.0 60.0 40.0 20.0 0.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Types of Offence Under 20 Years 20-29 Years 30 Years and Over 18 Researchers' Serious Cheating: 1 Copying from another student in a test. 2 One student allowing another to copy from them in a test. 3 Taking unauthorised material into a test. 4 Giving answers to another by signals. 5 Receiving answers from another by signals. 6 Impersonating a student in a test. 7 Paraphrasing without referencing. 8 Copying published information without referencing. 9 Copying information from another student without consent. 10 Paying another to complete an assignment. 11 Falsifying the results of one's research. 12 One student allowing another to copy their assignment. 13 Writing an assignment for someone else. Researchers' Minor Cheating: 14 Continuing to write after a test has ended. 15 Padding out a bibliography with references that were not actually used. 16 Copying information with reference to source but no quote marks. 17 Collaborating on an individual assignment. 18 Preventing others from accessing resources needed for an assignment. Figure 3: Actual Offences Admitted by Students (by Age) Percentage of Respondents 100.0 80.0 60.0 40.0 20.0 0.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Types of Offence Female M ale 17 18 Researchers' Serious Cheating: 1 Copying from another student in a test. 2 One student allowing another to copy from them in a test. 3 Taking unauthorised material into a test. 4 Giving answers to another by signals. 5 Receiving answers from another by signals. 6 Impersonating a student in a test. 7 Paraphrasing without referencing. 8 Copying published information without referencing. 9 Copying information from another student without consent. 10 Paying another to complete an assignment. 11 Falsifying the results of one's research. 12 One student allowing another to copy their assignment. 13 Writing an assignment for someone else. Researchers' Minor Cheating: 14 Continuing to write after a test has ended. 15 Padding out a bibliography with references that were not actually used. 16 Copying information with reference to source but no quote marks. 17 Collaborating on an individual assignment. 18 Preventing others from accessing resources needed for an assignment. Figure 4: Actual Offences Admitted by Students (by Gender) 14 Steps Percentage of Responses Discuss cheating/academic dishonesty openly and strongly with students, making expectations extremely clear. 70.8% Supervise test/exam situations more closely. 46.0% Frame assessments in a different way. 35.4% Closely monitor group assessment to ensure marks are allocated on the basis of individual merit. 31.9% Build a close relationship with the students so that a sense of honour develops. 30.1% Change the seating arrangement or otherwise change the physical environment during tests. 26.5% Have smaller classes, allowing better relationships to form with students and greater opportunities for observation. 24.8% Reduce or eliminate the number of take-home assessments, preferring to use supervised 23.0% tests/exams instead. Change grading or marking practices. 16.8% Negotiate a Code of Honour or something similar with students. 8.0% I have taken no steps. 3.5% Table 3: Steps Taken by Academic Staff to Minimise Academic Dishonesty 15 REFERENCES Fishbein, L. (1993, December 1). Curbing cheating and restoring academic integrity. The Chronicle of Higher Education, P. A52. Genereux, R., & McLeod, B. (1995). Circumstances surrounding cheating: A questionnaire study of college students. Research in Higher Education, 36 (3), 687-704. Kibler, W. L. (1992). Cheating: Institutions need a comprehensive plan for promoting academic integrity. The Chronicle of Higher Education. November 11, B1-B2. Lupton, R. A., Chapman, K. J., & Weiss, J. E. (2000). A cross-national exploration of business students’ attitudes, perceptions, and tendencies toward academic dishonesty. Journal of Education for Business, 75 (4), 231-236. McCabe, D. L. (1993). Faculty responses to academic dishonesty: The influence of student honor codes. Research in Higher Education, 34, 647-658. McCabe, D. L. (1999). Toward a culture of academic integrity. Chronicle of Higher Education, 46, 87-89. McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K, & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Dishonesty in academic environments: The influence of peer reporting requirements. The Journal of Higher Education, 72 (1), 29-45. Ministry of Education. (2001). Accessed on 21 May 2002 from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/web/document/document_page.cfm?id=7108&p=1028.1051.6142.7211 Ministry of Education. (2001). Accessed on 11 June 2002 from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/web/document/document_page.cfm?id=7210&p=1028.1051.6143 Payne, S. L., & Nantz, K.S. (1994). Social accounts and metaphors about cheating. College Teaching, 42 (3), 90-97. Pulvers, K., & Diekhoff, G. M. (1999). The relationship between academic dishonesty and college classroom environment. Research in High Education, 40 (4), 487-498. Roig, M., & Ballew, C. (1994). Attitudes toward cheating of self and others by college students and professors. Psychological Record, 44 (1), 3-13. Simon, C., Carr, J., DeFlyer, E., McCullough, S., Morgan, S., Oleson, T., & Ressel, M. (2001, October). On the evaluation of academic dishonesty: A survey of students and faculty at the University of Nevada. Reno. Paper presented at the 31st ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference. 16