Penn State University Storage Tank Management Program September 26, 2001

advertisement

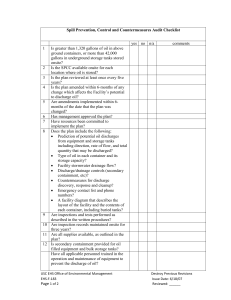

Penn State University Storage Tank Management Program September 26, 2001 Revised February 13, 2008 Revised September 3, 2014 Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 II. Federal and State Regulatory Requirements ............................................. 1 III. Oversight of Existing Storage Tanks ....................................................... 3 IV. EHS Requirements for the Selection of New Tanks ............................... 3 V. Requirements for Environmental Emergency Plans ................................. 4 VI. Training ................................................................................................... 5 VII. Oversight of Clean-up of Spills and Releases........................................ 5 VIII. Program Highlights ............................................................................... 5 I. Introduction Petroleum products are stored in aboveground and underground storage tanks, as well as drums throughout the university. These petroleum products are used primarily as a fuel for heat, emergency generators, vehicles, and other university machinery. In addition, chemicals and oils are stored in aboveground storage tanks and drums. The storage of these materials, while necessary, is a potential environmental hazard due to the possibility of spills, leaks, and releases. Any oil or chemical spill can pose a serious threat to both the environment and human health, and may result in significant costs for clean-up. A single pint of oil released into a surface water body can cover up to one acre. The threat to the environment is not limited to surface water, but includes soils and ground water as well. Spills can destroy aquatic habitat, and it may take years for recovery. The Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska, which was the largest spill in the United States to date (approximately 11 million gallons), occurred in 1989 and caused environmental degradation that continues to exist today. Despite the nation’s best efforts to prevent them, the EPA cites that almost 14,000 oil spills are reported per year. Penn State is committed to reducing its environmental risk to the minimum possible while continuing to function as a leading research and teaching institution. To that end, the Storage Tank Management Program is tasked with ensuring that the tanks throughout the university system (with the exception of Hershey Medical Center) that are used to store petroleum products, oils, and chemicals are safe and environmentally sound. The program is administered by the Department of Environmental Health and Safety (EHS). II. Federal and State Regulatory Requirements Currently the University is regulated by three authorities, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the PA Department of Environmental Protection (PADEP), and the PA Department of Labor and Industry (L&I). The pertinent acts and regulations for each are discussed below. In 1973, the federal government passed the Clean Water Act, which resulted in the promulgation of the "Oil Pollution Prevention" regulation, identified as Title 40, Federal Code of Regulations, Part 112 (40 CFR 112). The Clean Water Act was amended by the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, and requires that facilities that are subject to the regulations prepare and implement a plan to prevent any discharge of oil into navigable waters or adjoining shorelines of the United States. The plan is referred to as a Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasures Plan (SPCC Plan). The act, as amended, provides requirements for underground and aboveground storage tanks, and containers and oil-filled equipment of 55-gallons or greater volume at facilities which meet threshold storage 1 volumes (1,320-gallons of aboveground storage or 42,000-gallons of underground storage). In 1965, the federal government passed the Solid Waste Disposal Act to improve solid waste disposal methods. It was amended in 1970 by the Resource Recovery Act. In 1976, congress again amended this act to create a new program for the management of hazardous waste. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) provides for the management of both hazardous and non-hazardous wastes. RCRA was amended by the Hazardous and Solid Waste Amendments of 1984 (HSWA) which expanded its scope. The HSWA statute that covers underground storage tanks (USTs) is Subtitle I, "Regulation of Underground Storage Tanks." As a result of these acts, congress promulgated Title 40, Federal Code of Regulations, Part 280 (40 CFR 280), "Technical Standards and Corrective Action Requirements for Owners and Operators of Underground Storage Tanks," Part 281 (40 CFR 281), "Approval of State Underground Storage Tank Programs," and Part 282 (40 CFR 282), "Approved Underground Storage Tank Programs," all of which are administered by EPA. The Pennsylvania legislature passed the Storage Tank and Spill Prevention Act (Act 32, as amended) in 1989 in response to a large aboveground storage tank release. The act is broader and more far-reaching than RCRA Subtitle I, and establishes a comprehensive state (PADEP) regulatory program for both aboveground and underground storage tanks that is codified under Title 25 Environmental Protection, Chapter 245, and “Administration of the Storage Tank and Spill Prevention Program." These regulations include all of the federal regulations for storage tanks, with the exception of the Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasures Plan, which remains in federal control. While the EPA retained control of SPCC Plans, the PADEP requires Preparedness, Prevention, and Contingency (PPC) Plans for facilities that have the potential for causing accidental pollution of the air, land, or water, or the endangerment of public health and safety. This includes storage tanks that contain hazardous substances. The Fire and Panic Act of 1927 (commonly known as the Pennsylvania State Fire Marshal Law) also provided tank regulations, largely related to fire issues, which were administered by the Pennsylvania State Police. This law, as it applies to storage tanks, was repealed and replaced by the Combustibles and Flammable Liquids Act of 1998, which transferred the powers and duties of the state police to the Department of Labor and Industry (L&I). The Act resulted in the promulgation of Title 37, Part I, Subpart B, Flammable and Combustible Liquids regulations, Chapters 11, 13, and 14. In Allegheny and Philadelphia counties these laws are administered at the county level; at all other locations they are administered by the PA Department of Labor and Industry. 2 The Department of Environmental Health and Safety administers the Storage Tank Management Program and oversees the University’s adherence to the EPA, PADEP, and PADL&I regulations as they apply to the tanks throughout the university system. These include the placement of the tanks, the type of tank, the type of monitoring equipment on the tank, permitting of the tanks when necessary, and environmental emergency plans for all of the tanks. III. Oversight of Existing Storage Tanks The University has both aboveground and underground storage tanks, which have different inspection and monitoring procedures. The University follows the requirements for tank inspections as specified by the PADEP, the Steel Tank Institute’s Standard SP001, and the American Petroleum Institute’s API 653, depending on the type of tank. Facility personnel are required to inspect and monitor their storage tanks in accordance with their environmental emergency plan, which details the appropriate type and frequency of inspection for the tank (see Section V, Requirements for Environmental Emergency Plan, below). In addition, EHS performs regular audits of the University’s tank facilities to ensure that the requirements of these plans are implemented as well as to inspect the tanks and determine the need for maintenance, removal, or replacement. During the audits EHS inspects each facility’s records from the previous year, as well as the spill emergency response equipment. Site personnel are expected to be familiar with the environmental emergency plan and spill response. In addition EHS ensures that preventive tank maintenance is performed by certified contractors regularly, and in a timely manner. For example, all underground storage tanks that have cathodic protection are tested annually to determine if the tank’s protection system is functional. All electronic tank monitoring systems for underground storage tanks are tested annually to ensure that they are working properly. If during the course of maintenance, inspection, or for any other reason, it is determined that a tank needs to be removed, EHS coordinates and provides oversight for the tank removal, and, if necessary, for the replacement. EHS requires the tank remover to be a PADEP certified tank remover and to collect soil samples to establish that there is no contamination present when an underground tank is removed, even when not required. All removed tanks are cleaned and made inoperable prior to disposal. Closure reports are maintained by EHS to document the removal of all underground and aboveground storage tanks. IV. EHS Requirements for the Selection of New Tanks All new storage tank designs must be reviewed and approved under the Storage Tank Management Program by the Department of Environmental Health and Safety. The tank requirements are site-specific, and therefore only guidelines are given below. 3 In the interest of reducing pollution potential, EHS determines, with the facility manager, the need for a new tank and the minimum acceptable tank volume. In all cases, EHS will review the use of alternatives for the needed fuel or chemical prior to considering a tank for a new location. In addition, the volume required will be reviewed with the goal of minimizing the tank volume to a practical level, but not to so small a volume that the tank needs to be filled too frequently. EHS and the facility manager select the type of tank and best location for the tank based on best management practices. Wherever possible, the use of underground storage tanks will be strongly discouraged in favor of aboveground tanks that are either dual walled or have another means of secondary containment. In addition, new tanks are equipped with monitoring equipment, and spill and overfill protection to minimize the chance of spills, leaks, or releases. Tank locations are reviewed with both the needs of the user and the potential for environmental degradation should a release occur considered. For example, tanks are not located adjacent to sink holes, where a spill could be released directly to ground water. EHS provides oversight for any required tank permitting. V. Requirements for Environmental Emergency Plans Penn State University is required to have a variety of spill plans. The EPA under 40 CFR Part 112.7 requires Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasures (SPCC) Plans for facilities with a threshold of 1,320 gallons of aboveground storage or 42,000-gallons of underground storage in containers and equipment that holds 55-gallons or more. The PADEP requires Preparedness, Prevention, and Contingency (PPC) Plans for tanks containing hazardous substances. They also require Spill Prevention and Response (SPR) Plans for facilities that store greater than 21,000-gallons of regulated substances, which include fuels and some types of chemicals. These plans are being combined under the title Environmental Hazards Emergency Response Plans (EHERP). All of these plans detail measures that will prevent and control spills due to human operational error or to equipment failure. The plans contain operating procedures to prevent a spill, control measures to prevent a spill from migrating, and countermeasures to contain, clean-up, and mitigate the effects of any oil or chemical spills on navigable waters. Each plan is reviewed by the appropriate facility manager, and the manager and his alternate for each site sign the site’s plan, agreeing to implement all portions of the plan. EHS ensures that the plans are implemented by conducting audits of each facility (see Section III, Oversight of Existing Storage Tanks). The plans are updated by EHS according to the regulatory requirements to include any new spills, the corrective actions that were taken, and the plans for preventing recurring spills. EHS amends the plans whenever there is a change in the facility design, including the addition or removal of a tank, drum, or oil-filled machine/equipment. Refer to the EHS Environmental Emergency Plans program for more detail. 4 VI. Training EHS provides the initial training and annual refresher training for all employees who are involved with handling, storage, and/or clean-up of petroleum products, oils, and hazardous substances that are stored in tanks. The purpose of the training is to ensure that the Environmental Emergency Plans are in place and the components of the plans are implemented at each tank site. Training for new hires is to be provided by the facility manager for the site. The training includes pre-release planning for each storage tank at a site. It details the inspection and monitoring plan for the tanks and the responsibility of site personnel to perform these tasks. The training reviews possible indications of leaky tanks or spills and what to do should the situation be encountered. A review of the required preventative maintenance for the tank is discussed, as is site security. Personnel are trained in the countermeasures to be taken in response to a spill, including the proper use of absorbents, the locations of possible environmental receptors, and the reporting required if a spill or release occurs. The spill kit and other emergency equipment located at the site are reviewed and their use is explained. The facility manager and the emergency coordinator are identified, and their duties are explained. The regulatory reporting requirements are explained in detail. VII. Oversight of Clean-up of Spills and Releases In the event of a spill, leak, or release from a tank, regardless of quantity, Environmental Health and Safety should be contacted to provide guidance on clean-up and reporting requirements. We can be reached at 814-865-6391. For emergencies that immediately threaten the environment, and can’t be readily handled by the facility, the initial notification should be made to 911. The Environmental Emergency Plan for the facility provides details on addressing spills and releases. In some instances spills cannot be suitably cleaned-up by University personnel. In those events, a 3rd party contractor will be brought in to direct the clean-up. This may include directing the removal of contaminated soil, collecting soil samples to demonstrate that all contamination was removed, arranging for disposal of contaminated soil, and providing closure reports. If ground water contamination is suspected, further investigation will be undertaken, with appropriate remediation if necessary. VIII. Program Highlights Between 1985 and 2014, PSU removed over 360 tanks in an effort to reduce the potential for pollution, resulting in a decrease in storage volume of over one million gallons. 5 Replacement of removed tanks has been only when it has been demonstrated that a replacement is truly needed and has generally been with aboveground tanks of lesser volume. Most new tanks have been aboveground diesel tanks attached to emergency generators. There have been very few USTs installed recently at Penn State. The ratio of ASTs to USTs has been continually increasing, and in 2014 was over 20:1. 6