>> Helen Wang: Good morning, everyone. It's my... to welcome Dr. Roxana Geambasu, who is a professor at...

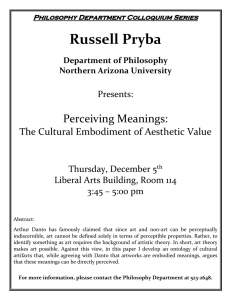

advertisement