20822 >> Kim Ricketts: Good afternoon, everyone and welcome. ...

advertisement

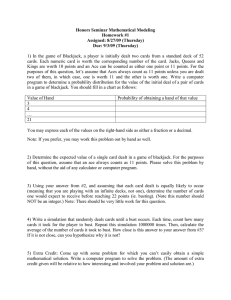

20822 >> Kim Ricketts: Good afternoon, everyone and welcome. My name Kim Ricketts, and I'm here to introduce and welcome Jeffrey Ma, who is visiting us as part of the Microsoft Research Visiting Speakers Series. He's here to discuss his book, "The House Advantage: Playing the Odds to Win Big in Business." Jeff and the now infamous -- infamous or famous -- MIT blackjack team used math, statistics and teamwork to beat Las Vegas casinos legally. He believes the correct amount of mathematical knowledge and outlook can help business manages unpredictability that comes with any venture. He graduated from MIT in 1994 with a degree in mechanical engineering; and following MIT he co-founded three companies, including Pro Trade and Citizen Sports. So please join me in welcoming him to Microsoft to discuss the House Advantage. [applause] >> Jeffrey Ma: Thank you. Thanks for having me. It's funny that you said the infamous/famous thing, because I don't know if you -- this is going to be a total nonsequitur. But how many have ever seen the movie "The Three Amigos"? There's a scene in the"The Three Amigos" where they're reading about this villain they're about to go face. His name is El Guapo. They said we're going to have to go find the infamous El Guapo. They're like what does infamous mean; they start thinking about it. Going infamous, infamous. It just must mean more than famous, he must be really famous. They got really excited to meet this really infamous or famous villain. Anyway, that was totally a nonsequitur. So how many of you guys have seen "21"? So you'll know that the greatest bit of Hollywood magic or what I would like to call Hollywood magic is how you turn an average looking Asian American male into a dashing white guy, because that was me. I was the inspiration for the main character of the movie "21" in the book "Bringing Down the House" and Jim Sturges, who is British, and is white. It's actually pretty funny -- first I want to introduce my sister who is sitting in the front row, who works here and has been here for eight and a half years. This is the first time she's ever heard me speak. So hopefully -- she's heard me speak a lot since I was like two -- but yet I still haven't stopped. There we go. So I can't remember where I was now. You made me lose my train of thought. The white guy. Always back to the white guy. So Jim Sturges played me in the movie; and, yeah, when I was walking into the premiere of the movie, and people always ask -- I'm sure we'll get these questions in a minute -- how much of the movie was true, how much of it was fake, the whole thing. What I always like to say is, you know, it was Hollywood. There was a lot that was Hollywoodized. And I was going into the premiere with my dad in Las Vegas. And I pulled him aside. I said, dad, I've got some bad news for you. What? Well, number one, in the movie you're dead and I'm white. It's one of those do you want the bad news or the really, really bad news? So I like to tell some stories that weren't in the book and actually weren't in either book. So I'll tell this first story actually, we'll just go over this quickly, but it's kind of a funny sports story. So any of you guys that are sports fans in here. Sports fans. So in blackjack, back in those days we had the opportunity to play blackjack with a lot of celebrities. And there was one weekend actually that we got to play blackjack with the New York Knicks. I think you were there. It was in Foxwood's Casino. It was during the NBA lockout. Any of you guys that follow basketball, you probably know that the NBA is headed for another lockout potentially soon because they pay guys way too much money and they don't make a lot of money on and on. So anyways we go to Foxwood's during the NBA lockout. And what do you think NBA players do when they can't play basketball? They go to casinos. I sat down, had the pleasure of playing blackjack with John Starks, the guy in the upper left-hand corner there. I sat down next to John. First of all, John, he's supposed to be this guy, this burly guy from the streets, orders a bottle of Merlot. And I'm from California, the Bay Area, and certainly wine is something I appreciate. But I wouldn't think this NBA player would be drinking Merlot. But I've since learned you never actually know what an NBA player is going to drinky, you can't judge a book by its color. I had the pleasure of playing craps about three years ago with a guy by the name Jalen Rose. Jalen's played for about 56 teams in the NBA, and he's now retired. And Jalen and I were playing craps. And we have some common friends because he was trying to get into sports media at that point. And I was already involved with sports media. And he said, hey, Jeff, let's grab a drink together. I said okay, Jalen, what do you want to drink? He said whatever you want to drink. I said, gosh, I don't know. My being a data-driven guy my one data point is that John Starks drinks Merlot, I'm not going to order a bottle of Merlot with Jalen Rose who is like 6'9" or anything. So I turn to the waitress, I have visions of rap videos going through my head. I turn to the waitress and I said, excuse me, ma'am, could you give us two glasses of Courvoisier. I didn't even know what Courvoisier is. The waitress starts to walk away, as she walks away, Jalen Rose grabs her and says: Excuse me, ma'am, could you make mine an apple martini? [laughter] Anyway, back to John Starks and his Merlot. John goes through this transformation that I'm sure many of you guys have seen your friends go through, I'm sure you've never done this, where you start at this intelligent human being walking into a casino sitting down at a table, and then five hours later become a drunk degenerate gambler. Poor John lost all of his money, pulls out his last $500 chip and puts it on the betting circle. Now the dealer gives him an 11 and the dealer has a 5 up. Anyone that plays blackjack here, what do you do? You double down, which means you need to put another $500 chip down. Unfortunately, John did not have another $500 chip. So I flip him a $500 chip from my stack, and he puts it down, and the dealer gives him a 5 to make 16. I told John, first of all, flipped the $500 chip, pay me back when you win. The dealer gives him 5 to make 16. John looks at me, he goes, man, you just jinxed me. Of course, I'm counting cards. So I know there's still a really good chance the dealer is going to bust. Don't worry, I think the dealer is still going to bust. Dealer flips the 10 to make 15, get 10 to make 25. John hands me back my $500 chip, doesn't say a word of thank you. And it was at that moment that I decided I would never have John Starks on my fantasy basketball team. [laughter] I really showed him. So all kidding aside, there's a lot of valuable lessons that, business lessons that I learned from my days playing blackjack. And that's why I wrote my new book "The House Advantage," which you guys have seen in the back. But the most important lesson, and probably my defining moment, most people have their defining moments like the birth of a child or getting married me. Me it's at a blackjack table. I was at Caesars Palace, and I was 22 years old, I'd been playing blackjack for about six months. And again we'll go into this a little bit later, but we're totally 100 percent objective. We use math to make all of our decisions. There's no subjectivity. And the math calls for me to bet two hands at $10,000. So I do. I get 11 on the first one, a pair of 9s on the second. And the dealer has a 6 up. So the 11, as we've covered with Mr. Starks, is a double down. So I put another $10,000 down. I get a 7 on that to make 18. The pair of 9s, I actually need to split. So I need to put another $10,000 down. That means I can play each 9 separately. I get a 2 on the first 9 to make 11. And again, for those paying attention, I doubled down. I put another $10,000 down. The dealer gives me a 10 on that to make 19. Sorry. He gives me an 8 on that to make 19 and then a 10 on the last 9 to make 19. Dealer has a 6 up. Dealer flips a 5 to make 11. He gets a 10 to make 21 and I lose $50,000. And this woman behind me shrieks: Oh, my God, that's my entire mortgage! And I want to turn around and go where the hell do you live, because I know here you're not getting a lot for $50,000. But, again, math and not emotion and using math to make decisions. So the math calls for me now to bet three hands of $10,000, and I do. And I get a 9 on the first one. I get a pair of 9s on the second, and I get a soft 15 on the third. And the dealer has a 5 up. So the 9 is again a double down. And so all these decisions that we're making are based on something called basic strategy, which, if you're ever going to become a gambler or want to gamble and play blackjack in a casino, you need to learn basic strategy perfectly, because the average blackjack player, the casino has about a 3 percent advantage over them just because the way they play. If you learn basic strategy perfectly, you can get the advantage the casino has over you about half a percent. Just by learning the right thing to do at all times and following it. So the 9, I have to double. And I get a 10 to make 19. Stand on the other 19. The last ace-4 I double also. Because it's a 5 against a 5. I get a 4 to make 19. I have three 19s. The dealer has a 5 up. About to lose either $100,000 or win back that woman's house. And it was one of those moments, this is one of those I wondered how in the world did I get here. So for me, I graduated from MIT in 1994. Mechanical engineering major, which I've done zero with. Like never once used anything of it. And I did this sort of rebellion where instead of going into the world of medicine I instead went into the world of finance. I was a pretty crazy kid. And then I went to work on the [CBOW] and then the whole Internet thing happened, which is great. Internet's been great. That's what it looks like. It's a big cloud. They don't actually depict Internet as a cloud anymore. Remember back in the day that's what it always looked like. No? So I went on to start three different companies. All three we've sold for different levels of success. The last one we actually sold three months ago to Yahoo. And during this whole time I was a professional blackjack player, professional card counter. I always like to throw up and pay homage to the inventor of the Internet because it's great that he did this for us. Now he can say he invented two things, one good, one bad. He invented the Internet. Probably none of us would be here if it wasn't for that. And then he invented global warming which wasn't so good. So the statement that people always say when I tell them I'm a professional blackjack player they say, one, isn't that illegal. Actually, it's 100 percent legal. It's been tried up to the highest level of the Supreme Court. It's just using your brain to beat a game. It's just like....what's your name? >>: Wenda. >>: Jeffrey Ma: Wenda, you and I play Monopoly all the time. You buy the crappy utilities and I buy Boardwalk and Park Place and I always win. One day you get mad, you throw up the board in the air, say this should be illegal. It's just using your brain to beat a game. What should be illegal about that? The second thing people say is are you banned from Vegas. There's no one that waits for me at the jetway at McCarran Airport and the minute I get there say Mr. Ma, sorry you have to turn around and go home. How many have seen "21," have seen "21" know that I'm in the movie, right? This is when you pretend you remember me in the movie, because otherwise this is very sad moment for me. I'm a dealer in the movie. I'm in the movie at about 56 minutes and 25 seconds, about. [laughter] And, no, really, I am in the movie. A small speaking role. Got a Sag card. Nominated for Academy Award, best actor in a movie that's about themselves that's in a movie for less than five minutes. But when I was out there filming the movie, I remember I sat down with the cast. And this little scene that I did, which I literally like have three speaking lines, the guy that plays me says, "Jeffrey, my brother from another mother," witty back and forth. Obviously not very memorable to anyone. That scene took me three days to film. So I was out there for three days. And one of the nights the cast said: Hey, Jeff, let's all go to dinner together. So we're heading over to dinner. And Kate Bosworth, who plays my love interest in the movie, pulls me aside. For all you males out here who have seen Kate Bosworth, if she pulls you aside, you say yes, Kate, what would you like? Kate pulls me aside and she said I've got a great idea. I said what's that? She said after dinner I think it would be really fun if we all go play blackjack. No, Kate, I don't know what a good idea that is. We're at the Palms. They know me really well. That's okay. You're with me. I'm a big star. They won't bother you. I said: Kate, it's been a long time since Blue Crush I don't know what a big star you are anymore. But what seemed like -[laughter] But what seemed like a horrible idea, about five bottles of wine later seemed like this great idea. So we go upstairs to the Palms Casino. The Playboy Casino there. I sit down, I start to play blackjack or try to play blackjack. The floor person looks at me and goes: Jeff, what you are doing? I said I'm here with Kate Bosworth from Blue Crush. No big deal, right? He said, listen, let me check. He calls upstairs. Comes back to the table and says not only are you not allowed to play blackjack, but if your little friend Kate is at the table you're not allowed to be within 20 feet of the table. Which was cool, because Kate all of a sudden thought I was like really cool, that gave me a lot of street cred because next day she was telling everyone on the set how cool it was. But not allowed to play blackjack. Not banned from Vegas. Sometimes not allowed to be within 20 feet of the table. The last thing people would say is remind me never to play poker with you. Now, the interesting thing is this really highlights the difference between blackjack and poker and why blackjack is such a great game to base the whole concept of data-driven decisions on. You can do everything right mathematically in poker and play against someone and all of a sudden that guy does something completely irrational and you lose. And the same is true when you try to use numbers to predict the market. You can do everything right and someone thinks it's a really good idea to lend a million dollars to some farmer who makes $12,000 a year to buy a house and no one would do that in our country, would they? No, probably not. But, anyway, so the point is that blackjack is completely irrational. The dealer has to do the same thing all the time. So why blackjack? Well, blackjack is the only game in the casino that's subject to something called conditional probability. Meaning what you see impacts what you're going to see. You contrast that to a game like roulette. One of my favorite stories from after the blackjack days were over, is I went out to Vegas with one of my buddies, my buddy Brian. As we head out to Vegas he said Friday night let's go, just you and me, coach me to play blackjack. I said okay. So we go, sit down at the blackjack table. To his credit he actually does everything I tell him to do, which is funny because now I'll go with my friends to a bachelor party to Vegas, we'll be sitting there, they'll be like, hey, why don't you come with us, tell us what to do, help us in blackjack. I'm like okay. I sit back there, like one of the old guys from the Muppets with a beer, watching them, critiquing them play blackjack me. They'll look at me and say, hey, what should I do on this hand. That's a hit, you should hit it. No, I don't want to do it. I'm going to stand on it. Then why am I here, then? But it's funny, it highlights this great thing I'll talk about later, which is let's say they have 13 and I tell them to hit it, they get an 8, I'm a genius. But if they get a 9, I'm an idiot why should they ever make a book or movie about me. And people tend to judge so much by you whether you're right or wrong by of the results versus the actual decision itself. Again, we'll talk about that later. I just thought I should highlight that. So back to our roulette story. So here I am with my friend Brian, and Friday night, after a couple of hours, we won about $2,000. So I turn to Brian and I say: We won; let's go out. It's Friday night. Let's go spend of this money at the club, like a reputable club, not the club you're all thinking about. So we go to cash the money out. And as we're going to the cage, Brian all of a sudden disappears. Where did Brian go? Before I can see anything or hear anything, all of a sudden I hear "thousand dollars on black." And I look over and Brian's on the roulette wheel. I walk up to Brian and I grab him by the shoulder -- before I can do anything, the roulette wheel is spinning. I hear "14 red." Brian lost half of what we just won. I pull him aside. I start to go and before I can do anything again, I hear "Thousand dollars on black." Now I'm getting a little concerned. I look at Brian. I go: What are you doing man? This is roulette. This is a loser's game. He says to me, "Don't you see what's happening here? I said what do you mean? He points up to this magical sign above the roulette wheel which shows the results of the last 20 spins. And the results of those last 20 spins, the last seven have all been red. So in Brian's mind, black is for sure coming up. Brian, there's nothing going on here. This is just roulette. Every spin is independent. It doesn't matter. It has no history. He goes, listen, I know you know math and I know you know blackjack, but I know gambling. And roulette's gambling. So buzz off. [laughter] Fool and his money are soon parted. I walk away. And three more improbable reds in a row, Brian's down $2,000 now. And I got to explain to him the folly in his ways. But the point is that people don't understand that often. They try to learn from history when history doesn't mean anything. They do that in craps. They think that the dice has some history that means something. But blackjack is different. If I take all four aces out of a deck of cards and hand that deck of cards to you, what do you think the chances of you dealing yourself blackjack are. Zero. No got no more aces. No way you're going to deal yourself blackjack. That's all that card counting is. Anyone understand -- this should be probably the smartest crowd I've ever spoken to, so I expect someone to get this answer. Explain the fish and the elephant. Fish have no memory. Elephants have a memory, memory -forget it. [laughter] All right. Now that makes a little bit more sense. All right. So back to counting cards. So there was a professor by the name of Ed Thorpe. And he was at UCLA at the time. And he and his wife wanted to go on a vacation to Las Vegas. But, of course, since he was the smart mathematical guy, he knew that the casino's edge was so big in so many games that he'd be a loser, basically, if he went and gambled. But on his way to Vegas, a friend of his handed him this study that had been done, which was done by these Army technicians and they used calculators to calculate this optimal strategy for blackjack, which we now call basic strategy. And he takes this strategy, looks at it and he says, gosh, I want to do this. So he goes to Vegas. And imagine that this guy, Ed Thorpe, wrote this book called "Beat the Dealer" which revolutionized blackjack. Then he wrote "Beat the Market" was the first quantitative hedge fund guy. Made hundreds of millions of dollars. He tells this story about his first time at blackjack table. Said to me: Jeff. I said, Ed, yes. He says, I went to that table. I had my card which told me what to do in every situation. I was going to play completely by the numbers. I'm like great. I started with $10. I said okay. See how much I ended up with? I'm like God, I don't know, $100,000, $200,000? $1.50. I lost $8.50. But everyone else lost all their money. And so that moment of only losing a little bit made him realize that blackjack might be beatable. And what he did is he took sort of his new technology, okay, and this is in the 1960s, his new technology was an IBM 704 computer, and he did simulations on how the odds of blackjack change when there's a deck with no 2s, or if there's a deck with no 3s or no 4s or 5s. Basically what he did is he simulated what it would be like when all the 2s were gone, when all the 3s were gone, and what he found is that when there's a lot of high cards left in the deck, 10s, face cards and aces, it's in the player's favor. When there's a lot of low cards left in the deck 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, it's in the dealer's favor and 7, 8, 9 were neutral. What he was able to determine when there was a lot of high cards left, the odds were in the player's favor, so he should bet more. When the odds, when there's a lot of low cards left, it's in the dealer's favor, so he should bet less or not play at all. So this is the most basic lesson from blackjack and really the most basic business lesson that I have. It's really just this idea that data changed blackjack. It changed it from 1930, when blackjack was introduced, to 1960, when people discovered card counting. People just lost at blackjack because they didn't pay attention to the data. They just lost. And in a lot of ways that's what's happening these days, that people are just still losing unless they utilize data in so many different industries, entertainment, media, in entertainment, media, medicine, sports, unless you utilize data there's so much out there and there's so much better technology to start analyzing that data, you're missing out. Now, there's some other things -- we're going to skip this one. So the reason that we focused on all this type of stuff, right, the numbers -- so many times we deal with, I deal with people because I've done quite a bit of work in sports, with sports teams. And ultimately I actually worked with the Portland Trailblazers, obviously Paul Allen's team, in basketball helping them decide who to pick in the NBA draft. Anyway, but ultimately using numbers helps you win. And we believe that winning is sort of the key and the reason you use numbers. It also helps you make difficult decisions. Now if any of you guys didn't believe I was in the movie. There I am. [laughter] I'm a dealer. And so the reason that that's up there, besides to prove to you guys that I was in the movie, is to remind me of one of the most difficult decisions that I've ever had to make. Okay. And one of the most unconventional decisions I've ever had to make. So I walked into, let's see where was I, MGM Grand. I had just learned something called advanced strategy or numbers plays, which basically you use the count, you use the information that you've gathered about what cards are left to actually vary your basic strategy. So you do some things that people would think are not with the book. So I walk up to the table, and the math called for me to bet two hands of $8,000, so I do. On the first hand I get a blackjack. So I win $12,000 on that hand. On the second hand I get a pair of 10s and the dealer has a 6 up. So believe it or not, there are times when you want to split 10s. Those of you guys who are mathematically inclined, let me explain to you why. Imagine that every card that you don't see is a 10. Is it a higher expected value for you to split those 10s or not? Of course it's higher to split the 10s. So but splitting 10s is very unconventional. It's something that people don't really like. When you split 10s, you have $25 on the table to production. When you split it when you have $8,000 on the table it's a production. So I go and the dealer looks at me and she starts to wave off my 20, and I said no, no, I think I want to split those. She said are you sure? I said, yeah, I do. So I put another $8,000 down. I get an ace on the first one to make 21, which is great. And then I get a 9 on the second one. And the dealer has a 6 up. Now, mind you, this is a $500 table. So everyone at the table wants to kill me right now. Because they believe I've just screwed up some cosmic karma in some alternate universe where I took someone else's ace in this other universe, now all of a sudden the dealer is going to make her hand because people -- there's a lot of smart people in this room who are like he did ruin -- no wonder I lost that one hand. I knew it was him. But no, people believe this stuff. That's kind of the funny thing about gambling, if you think about it. Because really smart intelligent rational people lose their heads. That's why it's such a funny thing. And in "The House Advantage" I talk about it why it's such a funny thing to think about in terms of business, because there's times in business where people lose their head because of emotion also. So here I am. I've done this and the dealer flips a 10 to make 16. And I get to 10 and make 26 and win. I win another $16,000. I pick up my chips and I run away from the table because I don't want to face the wrath of the other people at the table. But I started thinking about why this decision was such a difficult decision for me. And there's a lot of reasons why. And a lot of them are really good, interesting kind of business lessons. The first one has to do with something called omission bias. So in blackjack, so many of the times, I talked about giving advice to people on what to play. So many of the mistakes that people make in blackjack are ones of inactivity. So imagine that I have a 15. There are people that would just say whenever they have 15 they're not going to hit it, no matter what the dealer has, because they don't want to bust. They don't want to be the one that takes the card and ends the game. They'd rather at least let the dealer play it out because they still have a chance to win. But that mistake is a horrible mistake from an odds and math perspective. That's something called omission bias where we as individuals -- we do this in our lives, think about decisions you make all the time, you favor maintaining status quo over taking chances, or making a decision. And we do it in our personal lives, too. I always allude to that couple or that friend that you know is in this relationship that's horrible. And every day they wake up and they just want to go with the relationship, because maintaining status quo is easier than breaking up with someone. But they have to realize that decision to maintain status quo is a decision to maintain status quo. So just standing on that 20 was the easier thing to do but ultimately it wasn't the right thing to do. The same thing is -- there's another bias called loss aversion. So we are more impacted by a loss than we are by a gain of the same amount. And so I'm adverse to losing, because I think, gosh, I got 20. I don't want to lose that, right? I don't want to lose the opportunity to win that money. But, ultimately, as an organization, right, you should always be thinking about how do I make the most money, not how do I protect what I have already. I hope this one should hit kind of close to home, right? Just to put it in perspective. This week I've been to Facebook. I've been to Google and now I'm here. And I'm at Facebook telling the story, and I was there, it was actually last week that I was at Facebook, I was there the day they announced that they got to 500 million active users. That's a lot of people. And as I'm there talking to the crowd, I'm the only person that's ever spoken at Facebook twice. I'm tied to that company very well. I'm saying this thing, so I'm saying now that you guys are at five -- because the first time I ever spoke there they had 40 million users. So in that time they've grown over tenfold. And I said now that you guys are at 500 million users, are you guys going to take the same chances that you took before or are you going to -- and this guy from the back row, who was on their executive team, Shimauth he screams: Hell, yeah! Because he knows that it's important that they're not averse, that they're not loss averse, that they continue to still take the same chances they did going forward all the way growing to where they are right now. And that's an important thing, because that's a hard thing to overcome. And then the final point actually is something that I'd love to illustrate by use of a good friend and near and dear to my heart, not really a good friend, but near and dear to my heart. Bill Belichick, the coach of the New England Patriots. Super successful. Won a ton of Super Bowls, won a ton of games but not very popular because he makes unpopular decisions and very unconventional decisions. He made this decision that was so unconventional this year against the Indianapolis Colts he went for it on 4th and 2 at his own 29-yard line, when his team was up by six points, and it didn't work. But it was unconventional, and the mathematicians would tell you that it was a good decision. I'm not here to tell you it was a good or bad decision, but I'm here to tell you how people reacted to the decision. I sat there with a guy by the name Bill Simmons, famous writer for ESPN. The two of us were arguing about poor Bill Belichick's decision. We went back and forth. And Bill finally, frustrated, threw up his hands and looked at me and said, you know what, we know it was the wrong decision. I said, Bill, how do we know that? He said because it didn't work. And I said: Really, is that how it works? So I have 19 and the dealer has 7 up because Bill's a big blackjack player. And I decide I want to hit that 19 and I get a 2. Was that a good decision? It had a good outcome. You laugh. There's a hedge fund manager that I know that mistyped a ticker symbol when he made a trade. He didn't realize it until three days later. But that stock went up 60% in that time frame. And he claims that was a good decision. [laughter] So separating the decision from the outcome is so important in how you look at things. So why do we make difficult decisions? We'll go over it quickly. We don't want to end up like this guy. We want to end up like this guy. That's Sean Payton. Now to give you guys an understanding of the power of using numbers to make you understand how to take risks. Okay. Now, Sean Payton, coach of the NFL, coach of the New Orleans Saints, who won the Super Bowl this year, made two very unconventional decisions in the Super Bowl. The second of which was a successful decision where he decided to go for an onside kick at the beginning of the second half. Onside kick is this very risky maneuver, because most of the time when you do it people expect you're going to do it and you only recover the ball 25 percent of the time. It's basically like this 1-in-4 chance that you're taking. Very risky. But what no one talked about is how there's a difference between surprise onside kicks and expected onside kicks. And surprise onside kicks are actually recovered 60 percent of the time. So six out of ten times. And it was a calculated risk by Sean Payton. And it helped them ultimately win. But he knew if he had made this decision a thousand times, he would have recovered it 600. Although it wouldn't have been a real surprise if he had done it a thousand times at that point. But the point is that he knew that this was going to be, you know, that this was a calculated risk. So one of the interesting things, and again kind of tying back to the whole idea of business and how we fit this into business, is you think about this guy, Sean Payton, you think about this guy Bill Belichick, and they're two of the unconventional coaches, managers, what are they called, coaches in the NFL. Why are they able to make these difficult decisions? Anyone know? >>: Data. >> Jeffrey Ma: They've got data. But everyone has the data. They're able to make these decisions for one reason. I was talking to a guy by named Daryl Morey, General Manager of the Houston rockets yelling and screaming how stupid it is that most NFL coaches knowingly make wrong decisions. He said to me it's not really wrong decisions for their set of preferences. I said what do you mean? He said ultimately their first goal is not necessarily to win the game. I'm like: How can that be true? He goes, their first goal is not to get fired. And so Bill Belichick and Sean Payton have the most job security of any coaches in the NFL. So they can just make the right decision, because them not getting fired and them winning are aligned. They have aligned incentives with the team, with the players, with the owners. There's a really great economist by the name of John Maynard Keens. I'm sure many of you have heard of him. He wrote this book, why do you guys shift in here, it's a lot of passion for Keens. But he has this great line that says history would teach you that it's better to fail conventionally than it is to succeed unconventionally. I'm paraphrasing a little bit. The actual quote is in my book. But the point is that these guys are just trying to protect sort of their jobs and self-preservation and on and on and on. And so much of like what you do in your jobs, in your lives, in your companies, should be set up in a way that you have people with common goals setting, like aligned goals. Right? That's a big key. The first guy, the rapper common, it's like Aribas. Worked with him here? No. Okay. Anyways, but the point is that common goal setting are aligned incentives are so important to success in an organization. Otherwise you have people who are worried more about self-preservation. You see it all the time in sales goals. Like people who are bonused quarterly in sales. And, again, I talk about this in my book. The idea of bonusing people quarterly is tough. Because sometimes they're focused on making their bonus, and they might not be focused on building the best or locking in the best customers from a long-term perspective. So it's definitely a difficult challenge. We're going to skip over fat guy right now. So let's go back to these four keys to making better decisions. First one, as I talked about, real life decisions are everywhere. A decision to maintain status quo is still a decision. And I think that that's an important thing to think about as you kind of like think about how you, how you innovate and how you decide what changes to make. The second thing is evaluate decisions from a true zero frame of reference. Don't think about, okay, I've made $10,000 right now, I want to protect that $10,000. No, you're not thinking about that. You're thinking how do I continue to grow and make the most money that I can for my organization. Clicker. There we go. Imagine you were able to make the decision millions of times. So what's your name? >>: Anish. >> Jeffrey Ma: Anish. So you and I are going to play a game. Ready? I'm going to flip a coin. If it's heads, okay, you're going to pay me a million dollars. Okay? If it's tails, I'm going to pay you $5 million. Okay. Do you want to play that game? >>: No, I don't have a million dollars to give you. >> Jeffrey Ma: Normally I have to bring in my big goons. I have to say I have five goons behind me; we'll settle up as soon as I flip that coin. Now what if I say to you, listen, you have an unlimited credit line with me. You can settle up anytime you want and you can play this game for as long as you want, now do you want to play that game? >>: Sure. >> Jeffrey Ma: Yeah absolutely. So to really make good quantitative decisions, you have to be able to, one, think about making the decision a million times, and, two, creating an opportunity for yourself to make that decision millions of times. In blackjack, one of the reasons that so many blackjack players fail who are good card counters is they go to Vegas with a thousand dollars and they bet $100 on a hand. Before they know it, the variance is they get on one standard deviation of variance and then all of a sudden they lose all their bankroll and they never have a chance to make that decision millions of times. And then my goons come and get you and they're shaking their money out until they get that money, right? So you think about that, too, in terms of finance and everything you do, you don't want to put too much of a bet in one area so that if you're making the right decision, which you hope you are, then you get to make that decision -- like if we played that same game and we just said hey we're going to flip a coin I'm going to give you a dollar or you give me a dollar you still want to play that game but you want to play it millions of times. And the final thing is Bill Simmons thing. Bill Simmons, the idea don't confuse the idea with the outcome of the decision. A bad outcome does not equal a bad decision. And the reason that I feel like this is such an important thing is that when you go back and you evaluate what you've done in your life and the decisions you've made in your life, if you just evaluate them based on the outcome, there's no chance that you're ever going to be able to repeat the success you've seen so far. You have to evaluate them based on the decision, the fitness of the decision. So let's go back to this big lesson, just to recap down 50,000. Woman behind me shrieking about her little shack in the tenderloin in San Francisco, and here I am I've got $50,000 out on the table. The dealer has a 5 up. Dealer flips a 10 to make 15. This math thing works. He gets a 6 to make 21. Maybe this math thing doesn't work. And I lose another $50,000. I lose $100,000 in two, three minutes. So I wander upstairs to my room at the Caesars palace, and I collapse on the floor and I stare up at the ceiling and I go why is there a mirror up there. But once I get over that -- [laughter]. I was 22. I didn't know why there was a mirror up there. I'm like do people get ready like this, how does this work? So once I get over that, I start thinking about my decision and what I had done. Not necessarily the outcome, I think about the decision. One, am I being, falling for a mission bias, am I filing for inactivity? Do I want to quit playing because that's the easy thing to do? Am I being loss averse? You know? Am I being impacted by this loss so much that I don't want to lose any more money? Right? Am I -- if I was able to make this decision millions of times, what would my decision be right now? Did I make the right decision, just suffer a bad outcome. And then finally, like, exactly, was it the right decision, the right outcome, and I thought about it and I said, God, I did make the right decision, it was the right thing, and I gotta go back down and play and give myself an opportunity to make this decision millions of times again. And I did. And I went down, end up winning back my $100,000. And I won an additional 50,000. Sorry, 70,000. So I was net up $70,000 for the weekend. And in so many ways I had wanted to quit. But I believed that was sort of first chapter of my book is called the Religion of Statistics because I really believed that's what made me like this believer in the religion of statistics, because I had had this like test of faith that I all of a sudden overcame and here I did. And I won. And I came back and I won and ended up having a movie and a book made about me, and now I get to talk to people like yourselves. So I think we have some time for questions. People have questions. Yeah, go ahead. >>: You play the market and if so where does the past performance does not guarantee future ->> Jeffrey Ma: Yeah, I think there's some things with the market that are interesting. One, I think the market is -- I think the market is tough just because it's so.different than blackjack for me. It's not perfect. I actually worked as a trader on the Chicago Board of Option Exchange while I was starting to do blackjack. And I felt like what we did on the exchange was gambling, what we did in the casino wasn't. No, I'm serious. I'm completely serious. And so for me, like -- I think there's little things that you can look at in the market. I think that having a long-term perspective is one of the best things to think about in the market because I think people always overreact to earnings announcements, right? Is this company that all of a sudden was one cent under earnings, does that suddenly make it a bad company because it just missed the estimates and it totally gets overblown? There's another idea, is just like RISKGAR or something like that, if you're looking at a merger, the blackjack principle of looking at a merger would say if you play the RISKGAR game, you have to make sure if one of them goes in your face you don't lose everything. But over the long haul you'll probably be doing pretty well. So there are little things that do in the market. >>: As you move from card playing into more realistic, more reality things like the stock market or sports teams, it strikes me that you're moving from tame problems to wicked problems, I don't know if you know that vocabulary and if so can you comment. >> Jeffrey Ma: I don't know. Can you explain that, the game of Wicket. >>: It's like Chess or Go, where maybe it's very complicated but ->> Jeffrey Ma: Got it. >>: Real world is just ->> Jeffrey Ma: I think that the key with wicket problems, is that what you call it. >>: Wicket. >> Jeffrey Ma: The key with those is you don't want to strive to have perfection in using numbers to solve those problems, you want to solve them in a better way than they've been solved before. I was one time talking to Billy Bean who is the subject of money ball, the general manager of the Oakland A's and he was talking about how it would be great to start using analytics in soccer. If you compare baseball, baseball is sort of a tame problem compared to soccer, which is a lot -would you say that analogy works with your terminology? >>: Yes. >> Jeffrey Ma: He says this to me about soccer. I said Billy it seems like it would be so hard to do something in soccer, to do something great in soccer. He goes you know what, you don't have to do something great, you just have to do something good. You just have to be better than what's being done right there. So I mean, I guess like my answer to you would be, hey, let's not focus on solving the world's problems, let's just focus on getting people to start to actually look at data before deciding which customers to spend more time on and which to spend less time on. >>: You mentioned the difficulty with trying to analyze poker as opposed to blackjack is the element of human error, the guy that you're playing against won't tell you what you expect them to. How do you account for human error in analyzing the success of sports teams. >> Jeffrey Ma: What kind of human error are you talking about? I mean, the difference -- okay just so we're clear -- the difference in poker and blackjack and sports teams and the market is just that there's so many more variables to try to analyze, right? You can analyze what will happen if people make bad mistakes or play badly. But that's just a whole other component and a whole other thing you've got to try to analyze. It's almost like there's too many unknowns. There's too few variables and too many unknowns in those cases. So I think in evaluating sports teams, again, the question you ask is a very good question, which is that blackjack is so perfect, right? The dealer is never all of a sudden just going to say, hey, I'm going to hit 17 because that's what I feel like doing today. So you don't have to model that potential. But what the key is is that when we think about these more wicked problems or this whole thing, we think about how do we get better at them. We don't think about how to make them perfectly. So I have a good friend that's a professional poker player his name is Andy Block. I'm sure some of you guys have heard of him played on the MIT blackjack team for a while. He and I talked about this. And I said Andy when do you use intuition? Like when do you use your gut to make these decisions? And he was like, oh, like he was gut in a traditional way but if I face a situation where I don't have a chance to model I'm going to look at whatever evidence I have in my brain at that point and it's not a pure data-driven decision anymore because it's not been modeled in the spreadsheet. So I guess there's just times where you face situations where you just have to do the best you can. Back there. >>: Can you talk a little bit how team play changed the basic strategy and the math and maybe specifically what about your chemistry of people trying to create alignment around the right math. >> Jeffrey Ma: That's a good question. Well, one, people always ask me, do you miss playing blackjack? I'm assuming I can drink this water? Perfect. I was just doing a television interview the other day and they had water in front of us and as I was leaving, so I was the first person in these six interviews. We're sitting at this desk there's water in front of us, I didn't drink the water. Thank God because remind everybody. I'm glad I knew that. Okay. All right. So anyways, the team dynamic of, first of all, people ask me what I miss most about blackjack. And it's not playing blackjack. I've played millions of hands of blackjack in my life and there's a reason the World Series of Poker is on ESPN and the World Series of Blackjack made it two seasons on the game show network. Not that interesting. But I do miss the teamwork, the camaraderie, the idea of here you are with four or five of your buddies going to Vegas to take down the man and then you go and you beat the man. You come back and I mean any of you guys that have been to Vegas, it's one of the funniest things, the flight to Vegas everyone is happy talking to the waitresses and everyone is so happy. The flight home, people are depressed, they're hung over. Don't want to talk to anyone. And we were the few people that didn't have that. Right? We went there. We were serious. We went home we were partying because we were happy. So that aspect of it that teamwork aspect of it I'll always miss. And in terms of the idea of team play, what team play did most for us was it made us more efficient. So it didn't really change the overall strategy. We still had people we would go to a table. I'd go in with about four or five teammates. There would be three spotters or back counters that would sit down at a table. They would count the table. Once the table got good, they would signal to us. We'd walk over and they would path off a code word to us. There's all these ways you can do it. In the movie this is dead on. Even words they use they used the word paycheck. Paycheck means 15 because people get paid on 15th of the month. I'm walking, the spotter might turn to the dealer say man you just took my whole paycheck I would know walking up to that the count was 15. So I would rub my nose. The universal sign for I know. I got it. And I would sit down it's funny because people go you weren't so obvious in the casinos like they were in the movie. And I was like yes we were. But you walk around the next time you're at a casino see how many people are doing things like folding their arms or folding their arms. It happens all the time. So that was really the team aspect. The other aspect of team play that is just so big is you realize how important trust is in any organization. So many levels of trust. The first level of trust is trusting people that you hand them $100,000 in cash and they're not just going to go run off with it. Trust that the people that are standing at the table, counting those cards for you, are doing their job properly so you can do your job properly. And I think about that a lot because I'm an entrepreneur. And it's the same kind of dynamic that happens when you go from a company of like two people, you and your partner, to a company of 15. If you don't trust the people below you to do their job effective I'm sure plenty of you guys have micro managers here who don't trust you to do your jobs effectively. You're like listen if you just backed off a little bit we'd be a much more efficient organization. Questions? Other questions? >>: When you look at the reason to global initial crisis, which is being described as the first mathematician--led meltdown, systematic meltdown, so do you ->> Jeffrey Ma: That's a crock of crap. [Laughter] >> Jeffrey Ma: I mean, it's like pretty simple what happened. And, first of all, just so you guys know, we have a once in a lifetime global economic meltdown every ten years. I mean, look at history. Every ten years -- this one was big. It was bigger than what we've seen. But it's the same kind of thing. People get irrational the market's overbought. It's very simple. People were trying to find ways to make more money. And maybe those were mathematicians, but the mathematicians weren't the ones that weren't being -- they weren't the ones ultimately that were deciding to do that. They were the ones being told to do that. Right, yes, they created CDOs, created all these crazy things that no one really understood. But is it their fault that like John Mack doesn't know what's going on in his own company and can't describe to someone what a CDO is. No, it's not the mathematician's fault, right? It was like the whole industry and it was the whole culture that just went crazy. Now that we all read books, Michael Lewis is a good friend of mine, we've read his book. If you haven't read it after reading my book read the Big Short. You probably read it. On Amazon it says like people are buying these two books together. It's mine and Michael's book I sent Michael a screen shot of it. I said Michael looks like our books are buying our books together, probably in slightly different quantities but they're buying them together. [laughter] when you think of those books that have been written and you read them don't you kick yourselves and say how did we all not see this coming and why aren't we all rich right now? There's some dynamic that we're all just wrapped up in this world of real estate just keeps going up and up and up and that's one of the things I talk about in my book actually which I think personally because I wrote it I think it's interesting. It's just this idea that in life, and even no matter how mathematical you are -- if you focus on history, the history would say, yeah, real estate always goes up. There's no problems, these mortgages will be fine because real estate is always going to go up. But what I tend to think about is that sometimes focusing too much on the numbers and not thinking -- you can think like a mathematician or you can think like a scientist. And a scientist would try to figure out why these numbers keep going up or why these mortgages are really looked for the root cause of all this. And I have a chapter that says think like a scientist, because I think you need to challenge these things. And maybe mathematicians helped, but if we had real scientists in there, we probably might not have gotten quite to where we were. Other things? >>: A few blackjack questions. >> Jeffrey Ma: Sure. If they're really, really specific blackjack maybe you should ask me afterwards. >>: No. >> Jeffrey Ma: Because we don't want to lose everyone. >>: Card counting in general. >> Jeffrey Ma: Sure go ahead. >>: One in terms of how deep they cut the decks now aday to prevent card counting from being useful is that invalidated and second when people go in try and play and they're nobody and they try to do card counting how much of varying their bit, $5 to a thousand dollars. >> Jeffrey Ma: If you go from five to a thousand dollars you'll probably get kicked out of a casino pretty quickly. >>: If you win got 10,000, $100,000 in front of you they want to kick you out of there, are you going to get to leave with your money. >> Jeffrey Ma: Yeah, they can't take your money. That whole thing in the movie. Like the movie starts out pretty good, like normal, solid then it goes a little sideways at the end. It's entertaining though the end is my favorite part. But the actual realisticness of it no isn't right. What was the last one. >>: Once you've been kicked out once, are you kicked out from everywhere? Do they all talk. >> Jeffrey Ma: No. I mean they all talk. Once you get kicked out from one place you'll probably have trouble playing at other places but you're not necessarily already kicked out of those places. >>: You can just -- you [indiscernible]. >> Jeffrey Ma: Yeah, you can do it for a while. Honestly if you guys want to try card counting, the key you want to keep it on a smaller scale and stay at bigger places and not have this -- you all have good jobs you don't need to worry about it -- but you don't need to think about this as making a living. Think about it as going to Vegas, getting some good comps and actually winning money or even coming out even, versus losing, like everyone else does. And not be so focused on making tons of money. Because you can go in like the Wynn these days and bet hundreds of dollars on a hand and they'll never notice; you could be a card counter for years there before they would care. >>: Before 21, there was a documentary on the history channel. Was that a better depiction of what actually happened or how close was that. >> Jeffrey Ma: Yeah, I think so. It was a documentary. So it was more accurate. When I watched 21 the first time I was like oh my God this isn't what happened. Then I went it's not the Jeff Maude documentary because there's like six people that would actually want to watch that. It's actually a Hollywood movie. So that's really -- it's called breaking Vegas, I think, on the history channel. It's pretty accurate. Yeah. >>: You've done a lot of works in sports and stuff. If you had to pick a sport today to bet on what would be the decision, if you want to say what would be the sport, but I'm more interested in the framework. Baseball ->> Jeffrey Ma: So anything when you're trying to get an advantage you're trying to find out where the inefficiencies lie, inefficiency in sports based on something called the availability heuristic. It's really a fancy way of saying people tend to remember things, people tend to put a higher probability on things that they can remember or they can envision versus things they can't. It's like say today -- there's a couple of ways you guys can all go home because you've got this horrible traffic around here, right. There's probably one way that you like to go most of the time. Imagine that -- because it's always the fastest way. Imagine that yesterday there was a big accident that way. My God that way is so slow sometimes I'm going to go that other way. Even though that's the wrong decision you're placing a higher probability on there being an accident again because that's what you can remember. So in sports betting a lot of times and in the market, whatever, people react to short-term things, things they can remember. In pro football one of the best ways -- it's very simple. It's not going to work all the time -- but most of the times teams that get blown out one week, the next week are a good value because people remember them getting blown out. Teams that crushed teams one week are good value the next week because people remember -- another thing is that you just -there's an article that just came out in ESPN the magazine about my book and about some of the stuff we talked about in the book. One of the things we talk about is fumbles. Look for things that, that have a high skew of when we're talking about it it has a high skew towards the results and doesn't really have that much to do with the underlying decision. So in pro football we all know that turnovers are huge, right? Turnovers cause teams to win or lose. But actually predicting turnovers is really hard and actually controlling turnovers are hard. Teams that have a lot of turnovers will be a lot of value. I don't know if that answers your question. >>: Like the stock market I think it's like more blackjack or poker. >> Jeffrey Ma: More like poker, more so. I think there are ways you can make the market more like blackjack by focusing, like a guy named Jim Simmons top hedge fund trader in the last ten years he would say the market is completely blackjack. >>: You mentioned the importance of data-driven decisions and a lot of times what we have these days is a mixture of both qualitative and quantitative data. So how do you actually bring in a lot of the qualitative in the math. >> Jeffrey Ma: You have to create ways to put qualitative decisions quantitatively, does that make sense? Let me give you an example. This is going to get a little deep for you guys. But the book The Blind Side. Have you read that? There's a whole thing in The Blind Side about how offensive linemen offensive tackles became one of the highest paid positions in the NFL. Yet there's no statistics in the world that will tell you whether an offensive lineman is a good player or not. That's a purely qualitative thing that people say. But there was one NFL executive that was not happy with that idea about this being purely qualitative. What he wanted to do was he wanted to put quantitative boundaries on it. He talked to about 15 different coaches and he said on any given play what can an offensive tackle do? They said it depends if it's a run or path. He started with the run or path. He said let's see if it's a run. It depends. What's their assignment? And what he ended up doing he came up with a decision tree of 32 different combinations that NFL offensive tackle could do on any play and created this new framework and then he set quantitative framework and then he had high school coaches that got paid in tickets to basically sit and watch game film over and over again and create a new statistic, a new quantitative statistic based almost on qualitative judgments about what an offensive left tackle can do. Does that make sense? >>: Maybe one more. >> Jeffrey Ma: Okay, one more. Sorry, go ahead. Go ahead in the back, sure. >>: Just a question about the movie, does the back room really exist like where they did the beating and everything? [laughter]. >> Jeffrey Ma: It does. It does exist. It's funny, though, they're like corporate the realistic thing they can't do anything to you because it's not legal. But they definitely try to indim date you. There's a book called card counting for the casino executive in other words how to catch card counters, number one thing they do they violate their physical space and try to intimidate them to see how they react. All right. Well, thanks, guys. [applause]