(Microsoft wav file 15990)

advertisement

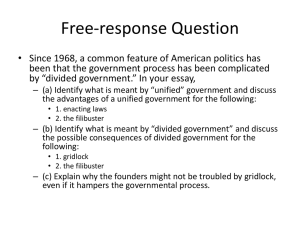

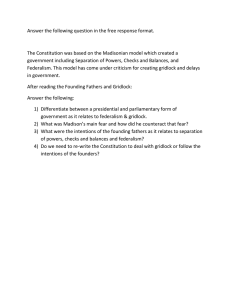

(Microsoft wav file 15990) >> KIM RICKETTS: Good afternoon, everyone. And welcome. My name is Kim Ricketts. I manage along with Kirsten Wiley the Microsoft Research visiting speaker series. Today we are going to take a tour of the gridlock economy. It's a place where 25 new runways we need to alleviate air travel delays can't be built because of too much ownership. A place where 50 patent owners are blocking a major drug maker from testing a cancer cure and a place where 90 percent of the broadcast spectrum is dead air because of too much ownership. How do we get to this place? Well, Michael is going to walk us through that pretty soon and there is a solution, thank goodness and Michael is going to walk us through that as well. So please join me in welcoming Michael Heller. He is the Lawrence A. Wein Professor of real estate law at Columbia University Law School. Please join me in welcoming Michael Heller to Microsoft Research. (Applause.) >> MICHAEL HELLER: Well, thank you all for being here and thank you for watching online. So here's the nut shell in a sentence. It's this: If too many people own pieces of one thing, then nobody can use it. That's the whole deal. If too many people own pieces of one thing, nobody can use it. Usually private property creates wealth, but too much private property has the opposite effect. It creates gridlock. That's a free market paradox I discovered and it's the core dynamic at the center of the gridlock economy. When too many owners control access to a single resource and cooperation breaks down, wealth disappears and everybody loses. In the next half an hour I will give you some concrete examples, some puzzles. The lexicon of gridlock and some fixes. I am perhaps the most -- I'm informed of this by Henry R, your magical AV guy, that I am the most low tech speaker you have had. (Chuckles.) >> MICHAEL HELLER: So I don't have any Power Points. I'm sorry. All I have is, I talk and I write stuff on the board. I hope that's okay for this audience. So let me start with a life or death example that's happening, happening right now. This is a story told to me by a drug company executive. He says that he has, he's pretty sure he has a better Alzheimers drug and he can't bring it to market. The reason is, he needs to test it against dozens, he needs access to dozens of patents to test his drug for safety and efficacy. So you have to imagine this guy walking into a room like this one, except it's filled with biotech patent owners, each of whom has a patent that is on the critical path for him getting his drug to market. So he has to negotiate successfully with every single person in the room or his drug doesn't come to market. And what's happened is indeed, this particular drug, the Alzheimers drug has been shelved. And even though it could save countless lives and earn him, he thinks, billions of dollars. This is not an unusual case. I detail in the book a number of other drug companies that face a similar problem. Drug companies face gridlock every day. How did that happen? It used to be in the biotech area -- this is a little afield for some of you, but in the biotech area, the basic inputs that you needed for drug discovery were in the public domain before 1980. So mostly the research was done with federal money and done in universities and then the results were put in public domain. Starting around 30 years ago, Congress and the courts switched patent law to allow more basic life forms to be patented and to encourage universities to commercialize the patents and commercialize their find. Those changes in the Congress and the courts sparked the biotech revolution and that is a great outcome. They created an entire extremely valuable cutting edge American industry. In the last 30 years, for example, we now have about 40,000 DNA-related patents that have been issued. There was an unexpected side effect to these reforms. That's where the gridlock economy story comes in. Biotech R&D has been steadily increasing year after year. From a fairly steady straight line up, but new drugs that actually cure disease at the end of that pipeline have been dropping. So what you have is a drug discovery gap. More money going in and fewer products that save human life coming out. I have been hearing these stories since I published an article in Science about ten years ago noting the possibility of this paradoxical relationship, that is between more patents and fewer products. But it's not just drugs that are suffering from gridlock. We see gridlock now across, if you look, you see gridlock across the entire innovation frontier. I'm going to give you a second puzzle as to which Kim gave you the punch line. And the question I want to ask is: What is the most underused natural resource in America? The most underused natural resource in America it turns out, you guys in this room may know, is the air waves. Over 90 percent of the spectrum in America is dead air. It's just dark because of how we have fragmented ownership of the air waves. We have thousands of license holders for spectrum who are fragmented geographically and restricted by use and prohibited from transfer. So they own little bits of ownership which are virtually impossible to assemble. So the process of assembling national high-speed wireless networks has been extraordinarily slow and costly in this country, compared to the rest of the world. Spectrum goes unused here while Japan and Korea are already a generation ahead. The U.S. just in the last decade has fallen from number one in global telecom innovation and products, number one, out of the top ten and this year almost out of the top 20. When you travel overseas you can see the future of communications. You see mobile shopping and entertaining as downloads, for example, of television and multimedia. You can't get this year yet. The loss is to the American economy in terms of innovation measure, from spectrum gridlock, measured in the trillions of dollars. That's a second example. Here is a third example that is a little bit more down to earth. We all of us waste weeks of our lives stuck in airports. And maybe some of you have wondered, why am I stuck in a airport? Why am I stuck? What's going on? And the answer is real estate gridlock. We deregulated air travel in this country 30 years ago. So let me ask you, how many new airports have been built in America since 1975? One. Where is it? >>: Denver. >> MICHAEL HELLER: Denver. Denver, the only airport built in America since 1975 is Denver. The ATCA, Air Traffic Controllers Association, says we can end air traffic delays in America completely gone with 25 new runways. That's a remarkable datum. We can end them completely. But you cannot build a new runway, or a new airport anywhere in America because too many owners, too many owners at the ends of the runways where the airports might get built block every project. Seattle is an interesting exception in that you are about to get -- you may not know this, maybe you do, you are about to get a new runway in SeaTac that has been in process for -- anyone know how long it has been in process for? Do you know when the need, the crucial need for a new runway in Seattle was identified? About 25 years ago. And it's supposed to come online in November. Anyway, that's an exception and almost nowhere in America do we see new runways in places that need them. So just a few more puzzles I want to just throw out there but I'm not going to talk about. Let me ask you a question. Why is it that African-American land ownership in this country has dropped 98 percent? 98 percent in the last 100 years? Why is it that rappers like Chuck D from Public Enemy today rap over a single sample and they no longer rap over the richly textured wall of sound that made up early rap? This may have been a puzzle to some of you. It was a puzzle to me. Why is it that we can't get clean wind energy from Texas where it's windy, to Seattle where you guys are actually willing to pay more for green power, for clean power. And just driving in today from Seattle, I passed Indie Mac which is right around the corner from you guys. You all know this, the big Indie Mac building on I20 which collapsed last week? How is it possible that Indie Mac which is tiny by comparison with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, how can they collapse? What is the cause to that? The answer to all of these puzzles is that all of these puzzles are really the same puzzle. Private ownership usually creates wealth, but too much ownership can create gridlock and gridlock blocks innovation. So my goal in mentioning all of these examples is to show you that gridlock is nothing fancy. This free market paradox is all around if you know where to look. There's been in the last generation an unnoticed revolution in America in how we create wealth. Ten or 20 years ago you got a patent and you brought your product to market. You got a copyright and you sang your song. You bought raw land and you built housing. That's the old economy. Today the leading edge of wealth creation requires assembly. Drugs, telecom, semiconductors, banking, particularly software which some of you know about, requires the assembly of innumerable pieces of intellectual property. It's not just high-tech that's changed, although high-tech is where a lot of my interest is. It's not just high-tech that's changed. Today cutting edge film and music requires the matching up and remixing of innumerable bits of copyrighted culture. Even with land, the most old-fashioned of resources, even with land the most socially important projects like new runways require the assembly of multiple parcels. So what's happened in America and actually this, I'm saying in America but this is true for every advanced economy. This is equally true in Europe and Asia. What's happened is that innovation has moved on. For the most part we are stuck with old style ownership that is easy to break apart and really hard to put back together. So the challenge is that rather than waste time and money dealing with assembly, a lot of the most, world's most powerful companies simply redirect investment towards less challenging areas where they already control the intellectual property such as extensions of existing products and by doing that they let innovation that is possible slip away. The flip side to this is that spotting and fixing gridlock is one of the great entrepreneurial opportunities of our time. We can reclaim that wealth that we lost to gridlock, but to do that takes, it takes a lexicon. It takes tools to unlock a grid and that's what I want to do next is give you the lexicon that you need to spot and then to fix gridlock. So ownership congestion, which is what I'm talking about, turns out to be a lot like traffic congestion. The difference is that we're all pretty familiar with traffic jams. But ownership jams are a little harder to see. So individually, right, most drivers are pretty reasonable people, but if 50 people from four sides of an intersection all want to turn left at once, then everybody gets stuck. It's the same with ownership gridlock. Each individual owner is usually acting reasonably, but the sum of their interactions is destroying wealth. When I discovered this dynamic, I called it the tragedy of the anti-commons. And that term has a history which I want to unpack for you. It's a twist on the term that a lot of you probably studied way back in college or grad school, the familiar concept is the tragedy of the commons. I want to break that down for those of you who are not familiar. If you imagine something familiar like the ocean or the air, any resource that we share, we tend to over use and often destroy. We over fish the oceans, pollute the air. That wasteful, that structure of wasteful over use we call a tragedy of the commons. The typical solution for tragedy of the common are two. Historically one major solution to tragedy, have the State come in and tell you what to do. Tell you who can fish, how much for how long, what you can take, state regulation. That's become a somewhat less attractive solution especially now with socialism dead. The other major solution, the most important solution to solving tragedy is privatization. Privatization is creating private owners. Why? Because private owners tend to avoid over use. If you control the lake, you invest in it. You protect it today so that you get more and bigger fish tomorrow. The secret for private property, the reason, the economic reason for private property more than anything else is this hidden conservation and wealth creation effect. Until now, the guts of ownership competition, markets, capitalism have been understood through this opposition. On the one hand, we have the commons which is prone to over use. And we have the solution which is to break it up into private property, each person in their little bit which is ordinary use. We think about the ownership of property, that's what we think about. At one end is the commons and at the other end we have private property. But that simple opposition mistakes the visible forms of property for the entire spectrum. The entire spectrum is larger. The danger is that privatization can over shoot. That's the anti-commons. And we can get to the point where we have instead of over use, we have under use. So that was the crucial tool that you need to spot gridlock, is to see the possibility that we can have wasteful under use caused by too many owners, exactly the same way as we can have wasteful over use caused by too few. Those categories are symmetric. The first is completely familiar. The second is completely hidden. But once you recognize the hidden half of the ownership spectrum, it upends or should upend your intuitions about what it means to have private property. It is not the end point of ownership. If private property is the end point, you can never privatize too much. All you're doing by privatizing is solving this tragedy of the commons, but if private property is not the end point, it's the midpoint of the continuum, you can go too far and you can blow right by well-functioning optimal amounts of property rights, right by private property into anti-commons property. At that point property destroys wealth instead of creating wealth. Making this type of ownership visible is a challenge. It hasn't been easy to figure out how to do it. That's been the challenge of this book is to figure out ways to frame the anti-commons in a way that makes it visible to people so they can see that it's nothing fancy. So that they can see that all these puzzles that you run into in every day life are really the same problem. So let me just give you two images that for me have been helpful and maybe they will be for you. One is robber barons and the other is big engines. The world's original robber barons were German barons on the Rhine a thousand years ago. A thousand years ago, the Rhine was one of Europe's major trade routes. And it was protected by the Holy Roman Empire. You paid one toll and you sailed the Rhine from Switzerland all the way to the Atlantic. When the Empire weakened, freelance German barons began building toll castles. At one point they numbered 200. Every couple of miles. And the sum of all those tolls made shipping impracticable. Why would you bother going from one end to the other if you're essentially going to have everything taken from you by the toll keeper. So for 500 years, for 500 years, the Rhine continued to flow, it still flows today, but for 500 years, nobody sailed up and down the Rhine. You simply stopped. And that, the effect of having too many tolls there was that everybody suffered. Even the barons. Even the barons were worse off. The entire European economic pie slang during the middle ages in part because of this problem of too many tolls, too little trade. Understand the gridlock economy today, which is the book, what you just do is update that image. So today's phantom toll booths arise whenever ownership is created. And you guys in the software business know that ownership is being created all the time in ways that you might not immediately recognize as such. So today's robber barons are often public officials who get the regulation wrong at the crucial moment when ownership is being born. But it can also be private companies that you deal with. Who have the bits and pieces of the technology that you need. Or it can be private individuals. So today the equivalent of the crushed trade from the Rhine is today crushed entrepreneur ship and crushed ability to innovate. So I remember the term my with my cell phone, several thousand patents read on every one of your cell phones. To get your cell phone into your hands, your cell carrier had to overcome the anti-commons. It took them a lot of work and they didn't necessarily get it right. So your Blackberry, for example, was almost shut down by missing potentially one of those patents. And it's not just the Blackberry. When I talk to patent counsel at telecom companies, at the say this is the biggest impediment to them introducing new products. It's partly the inability to get access to spectrum, but it's substantially the inability to be sure when they bring a new product forward that they aren't going to, that they can predict litigation cost, the follow-on litigation cost from people who come out of the woodwork and sue them for infringement claims on patents they didn't couldn't discover or didn't discover when the product was being performed. That's an extremely difficult problem for any new type of technology in the telecom industry. That's an example basically of robber barons blocking telecom today. All right. So the answer for why are the cell phones so slow, so pathetic in this country compared to abroad? It's gridlock dynamics. It is not thermodynamics that leads to tragedies with telecom industries. That's nothing -- all right. That's one way to think about gridlock. Here's the second way, which is big inches. In the mid 1950s, maybe -- let me be -- there's no one in this room who remembers the Quaker Oats Big Inch Giveaway. All right. All right, you're a young crowd. In the 1950s, Quaker Oats put deeds to square inches of Klondike land in specially marked cereal boxes. This was, for generations in business school, this was taught as the most successful marketing campaign in history. Millions of boxes of cereal flew off the shelves. This is my deed. And it's also reproduced in the book. So kids loved this. But imagine, there's 20 million of these out there. And they are one square inch of land in the Klondike. Imagine if oil is found underneath that square inch. There is no way you can drill ever if you had to negotiate with 20 million kids to get their square inches. If even one of them can block you, then no drilling happens. That's a pretty trivial example of gridlock, but when you're sitting on the runway or sitting in the airport or circling being delayed, it's the exact same problem. It's big inch gridlock that's keeping your, keeping these runways from getting built. You have landowners and communities at the end of every runway who are able under the way we designed our land use system in this country to block the construction of new runways. How did I discover gridlock? It wasn't sailing the Rhine and it wasn't drilling the Klondike. I first found out about, first saw gridlock in Moscow when I was there for the World Bank in the early '90s. I was there as the first team into Russia when the Soviet Union fell, collapsed in 1990. They invited the World Bank in to basically create markets, private property land and housing. I was the guy in charge of creating private property and land and housing. That was part of the bigger transition. And I stood in front of the Moscow Supreme Soviet and said here are some things you might want to think about doing. It turns out it's a lot harder to create private property and markets than it is to destroy it. Anyway, at one point Yegor Gaidar, who was the Deputy Prime Minister in charge of transition, asked, gave -- asked a question which is this: Which was a real puzzle. He had privatized store fronts a year earlier. But the stores were completely empty. And on the streets in front of the stores, the sidewalks, there were these little flimsy metal kiosks. This is a very cold place. These kiosk merchants and the shoppers were standing in cold directly across the sidewalk from completely empty, heated, lighted secure store fronts. The question Gaidar asked me was: Why don't these merchants come in from the cold? Don't they know better? And I, so I stood there with my forehead stuck against one of these windows trying to think of something halfway smart to say back to this guy in the couple days I had to figure out. What I discovered is that it's really simple to set up a kiosk. You just bribe a few officials; you choose your Mafia gang that's going to protect you; and you open your kiosk. By contrast, setting up a store was a lot more difficult. The way that Russia privatized store fronts, was by instead of saying you get store A, you get store B and you get store C, they said you get the right to sell the store and you get the right to lease the store, and you get the right to occupy the same store. The same store. Which meant that all these guys had to agree with each other for anyone to do anything and the result was that stores stayed empty. Russia went quickly from having too few owners to having too many owners and now those empty store fronts were my first literal glimpse into a tragedy of the anti-commons, or in plain English, too many cooks spoil the broth. This is a very simple idea. But it has a lot of explanatory power. Moscow store fronts are far away, but missing drugs slow telecom, sitting on the runway, a near infinity of problems are the same problem. After I discovered this path of the ownership spectrum, James Buchanan whose Nevada you his work you know, the economist Nobelist who helped create the public choice theory. He said yeah, this is right. And he wrote, he published a paper modeling the anti-commons and basically showing that my intuition that this, half of the ownership spectrum existed was right. And was symmetric to the problems of the commons. Since then, later, two years ago a business school researchers discovered that when business people negotiate dilemmas between, among themselves, when the dilemma is posed to them, when it's framed for them in anti-commons terms, people have to block each other, the people who are negotiating do a worse job. They get worse outcomes than if the identical dilemma is posed for them, is framed for them in commons terms. Which is interesting. So mathematically, these are symmetric, but in practice people have a harder time working themselves out of an ownership structure that leads to underuse because it's invisible, I think, than over use, which is much more visible. It's easy to see pollution. It's hard to know where you go to protest for the products that Microsoft is wanting to create but hasn't been able to because the IP situation is too fragmented. The word underuse isn't in most Dicks fares. That's amazing to me. Until three years ago underuse wasn't a legitimate Scrabble word. Isn't that incredible? Wasn't a legitimate Scrabble world. Now it is. When I was writing the book shall it still wasn't and may fact checker said actually, now it is. So I learned something. Anyway, this is an idea, it turns out I hope, to be useful equally in the left and the right. So far that's the reception that the book has had. Conservatives say this book is a story about the costs of misregulation. And liberals say this is a story about the cost of excessive privatization. And those are flip sides of the same story. No matter where it is that you stand politically or on what side the academic business divide you're on, this game, gridlock is a losing game for all the players. So time is short. I'm going to stay at 30 minutes. Let me wrap up. In the book I take you, I hope you all leave with the book. I take you on a tour of gridlock, the key gridlock battle grounds that I have seen. I talk about rappers and the FCC officials. I have a language pirate tale. If you guys are into pirate tales, there's a pirate tale in the book. There's a bunch of ways to spot gridlock and a bunch of ways to fix it. Let me mention the key ways to fix it. First, it's entrepreneurship. You can get rich by assembling property. People get rich by assembling patent pools. The reason your DVDs and jpgs work in any player, the patent owners voluntarily assembled those patents so that instead of each of them earning nothing, all of them could earn something. It's the same with copyright collectives, which is why you can hear music on the radio. Legislation. The second path to fixing gridlock is legislative and advocacy, and your rice part. So for example in the book I show -- right now it's really hard to assemble land in this country. You either secretly buy it up, which doesn't usually work. or what you do if you're a developer is you have the government condemn the land for you, which people hate. It drives people nuts when the government uses eminent domain. Those are the only two options. In the book -- once you realize the problem is gridlock, you can begin to see hey, we can have analogies to things like patent pools or, in this case, analogies to condominiums for assembling land. I propose in the book something called Land Assembly Districts, LADs. You have to have a cool acronym like LADs to sell it. I proposed LADs as a way to let neighbors decide for themselves if they want to sell. Similarly with patent gridlock, the most heavily lobbied bill in Congress this year, the bill that only a handful of you heard of but most of you didn't, was the bill to fix patent gridlock. It was a bipartisan effort and it just died because basically high-tech America couldn't strike a deal with the big pharma. So even though, there wasn't a left right divide. It was a high-tech America coalition divide that killed it. There has to be room there to strike a deal. That is, there is a way. I'm pretty confident, to design a law that protects drug maker's ability to earn a profit and has them get out of the way of the rest of us who need reforms in order to be able to fairly and efficiently assemble property rights for valuable new products, including the drugs that might save our lives. The third path is philanthropic. Here I talk in the book about one of the, I think the best examples of overcoming gridlock which is the malaria vaccine work that Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has done. I'm not talking to you about it just because I'm here, but I think it's probably a fabulous way, method for how you cure gridlock. What they did is, they went and -- they discovered that part of it what was blocking vaccine research for malaria, one of the world's worst I will canners, there were dozens and dozens of patents that you needed in order to just do the first couple of steps along the path to vaccine development and they bought them up and made them available widely so researchers don't run into this patent ticket on the first stage of, on the first stage of research. So that's the philanthropic solution. But the most important, the sickle most important key, I think, to fixing gridlock is to see it. It's to make it visible and give it a name. Then we can see what the links are am these puzzles. We can leverage from one area to another. People can work together in coalitions when you realize that you're facing the same problem with other industries who you may not realize are facing the same problem. There's nothing at all inevitable about gridlock, it's not thermodynamics. It's decisions we make about how to control the resources that we value, we value the most. This, so about the book was released yesterday and there was just a review on Slate I guess Monday, on slate.com by Tim Wu, probably most of you know his name. It was Move Over Marx, he was reviewing the book and he talks about what he calls the compendium of counter-intuition. Books like Gladwell's books and Suroweki's and Chris Anderson's Long Tale. He said this is part of this compendium of counter-intuition. I like that framing because the idea of this book is to give you easy access to one big new simple useful idea about how to innovate today. So that's what the book is aimed for, for people who are interested in innovating, people who are interested in seeing the hidden workings of everyday life or just interested in assembling resources for positive change, this book is for you. What is most exciting about being here at Microsoft, for me, is that more than anyone, you guys are at the cutting edge of these problems in the economy. So you probably -- I'm going to stop in one minute. You have dealt with this problem more than I have and you are you have probably come up with solutions more than I have. I look forward to hearing that from you. Thanks a lot. (Applause.) and the floor is open. How does this work? Right here in front. >>: I have no doubt that the lack of new runways is the result of the anti-commons. However, the air traffic delays aren't cussed by that. They are actually caused by the tragedy of the commons. >> MICHAEL HELLER: I like that, good. >>: You can get in your airplane and key up the mic and request taxi. There's nothing that says there's only five slots today and there's no regulation about that whatsoever. In fact, we pilots like it that way. >> MICHAEL HELLER: Of course, you do. Small pilots get there and -- one of the interesting things about small pilots, when big jets take off, you can space them fairly closely because they can blast through the weak of the jets in front of them. But small pilots have a longer lead time between planes. So you get a small plane on the runway, you slow down the entire airport because there's a small plane, and one guy takes off. Which points to tragedy of the commons and it points to a second problem. One of my favorite headlines when I was researches this book was a headline that says gridlock in the search for air travel delay gridlock solutions. (Chuckles.) >> MICHAEL HELLER: And the problem is that these are multiple forms of mispricing of airplane take off slots. So you can, there's lots of different margins along which you can operate. You can charge the little pilot guys a lot of money, if you charged them the scarcity cost of the space they are taking up, which we don't do. That would have a lot, that would free up a lot more space. >>: What that does, is -- SeaTac charges and the other airports don't, so we don't use SeaTac. We use Boeing Field, and Boeing Field is actually segregated airspace. It sort of sorts itself out. What doesn't sort itself out is other airlines creating additional flights. They can't do that. They don't have any permission to do this. >> MICHAEL HELLER: And this is going to be true, you press me on any examples or any of the other ones in the book, there are multiple course sources of anti-commons gridlock and there are multiple sources of each of these problems. So we could have more congestion pricing. We -- air paths in this country are very heavily restricted. We are in the process of moving towards freeing people up from having single pathways. So they can fly, they can find their own pathway and not bump into each other. There are a lot of different reasons why we have air travel gridlock. New runways would go a long way, at key airports would go a long way towards fixing it. But like when you build a new lane in the highway, you have to be thinking about other ways to limit people from simply filling that up as well. It's not the only problem, the only solution. Congestion pricing for slots is a good idea. >>: Have you looked at or applied it to state large corporations, the size becomes too much micro ownership? >> MICHAEL HELLER: Internally. >>: Internally. And that causes a kind of paralysis or gridlock. >> MICHAEL HELLER: That's interesting. Do you have an example, Microsoft excluded? >>: Microsoft. >> MICHAEL HELLER: No, the problem with assembly knowledge, one of the standard interesting problems that ->>: (Off microphone.) >> MICHAEL HELLER: Yeah. >>: They have to sort of distribute ownership and get siloed and then they become victims of their own ->> MICHAEL HELLER: That's interesting. I haven't thought about it internally within a corporation, but of course that has to be right. It's certainly true within the regulatory, on the public side, one of the pieces of the sub prime story is that we designed a set of financial instruments that were intended to take advantage of the existing regulatory scheme which is a scheme that fragmented decision making control among multiple regulators, no one of whom had the ability to say no, this is crazy. They each had the piece but no one had the big picture. Of course it's going to be true within a corporation as well. >>: And it's taking a less -- (Off microphone.) attempt to go address, too, we have to have the SFCC and we have to have the feds to remedy the problem. It's an interesting problem -- so there's your next book. >> MICHAEL HELLER: No, my next book is exactly that. The next book is focusing harder on this question of how do we take away the impediments to innovation in high-tech America? That's what this book is about, but really focusing much more concretely. One of the things we don't have now is good industry specific data on what really are the costs of the patent system to innovation on balance. Are we doing better or worse? So yeah, I think that's incredibly interesting area. >>: One thing more. From what I understand, the problem was innovation in the very bad way because you're creating new types of instruments and ->> MICHAEL HELLER: You know, a lot of the financials institutions that are falling apart right now are designed specifically with the stupidly organized fragmented regulatory system in mind. They were designed specifically to avoid regulation by those, by any particular one of those regulators. You can do that by carefully structuring your bond instruments. So yeah, so it's all, it all interacts, but Indie Mac is, it's a great gridlock story, I think. Yeah? >>: I have a question. The tragedy of the commons is over use. Right? >> MICHAEL HELLER: Right. >>: So my sense is that it doesn't really apply to intellectual property, right? Sort of intrinsically it doesn't apply to intellectual property. >> MICHAEL HELLER: If I have an idea, how can you over use it? >>: Exactly. I guess what I'm wondering then, on this spectrum then. >> MICHAEL HELLER: Yeah. >>: If you are thinking about the best sort of place to be out on the spectrum for intellectual property, you know what I'm saying, best in sort of the socialist sense, the greatest good for the greatest number, on this end and not on that end? >> MICHAEL HELLER: There isn't going to be a single answer. Part of the brief of the book is to just alert you to asking that question. Right? Just to say, okay, we have to think about how we design these structures with these two extremes in mind. It isn't just the case that having more patents is going to create more wealth. It might be, but we also ->>: -- the owner of the patents. >> MICHAEL HELLER: Not necessarily. When you think about the toll, the robber Barons on the Rhine, everyone lost out. And that seems to be the case from the patent system as a whole right now. The costs of litigation generated by the patent system exceed the entire benefit, economic benefit to the corporations that own those patents as a whole in the country, which is really a remarkable figure. We think patents as a whole are generating several billion dollars in net value to the corporations that hold them and litigation per year is on the order of 10 or 12 billion. So yeah, for ideas, you know, this is -- for innovation and ideas, once you have the idea, the best price for the idea is zero. Because if I have the idea, then you use the idea, we want everyone to use the idea. We want to price it at zero. But if the price is zero, why should I go to the trouble of having the idea? The intellectual property system in general is more than other areas of property, is understood as an area where Congress constitutionally is instructed to do, right, copyright and patent are in the constitution. Commanding Congress to create the system to promote innovation, promote progress, is to find the right balance. That is, giving enough protection to spur the optimal level of innovation, but not one iota more because then you're simply creating a monopoly with no countervailing social value. The goal of how much should there be in the system is to minimize the costs of over use and minimize the cost of under use. Now, how do you do that programmatically? It's hard to do in any area, but my goal is to make you ask those questions. If you're asking that question, I feel like I've already done my job. That's good. All right. Floor is open. Yeah. >>: Are you familiar with the work in White Spaces that Microsoft and other companies are doing with the FCC to overcome the telecom. >> MICHAEL HELLER: I can explain it, but why don't you explain it. You probably know more about it than I do. >>: The part I can explain without losing my job. >> MICHAEL HELLER: Always a risk. >>: Notionally, you can sense whether a particular spectrum resource is in present use or not and use it at lower power or in some other constrained way, getting out of the way of the actual quote owner or primary user, if that primary user decides to then step up and start using it. >> MICHAEL HELLER: This is one of the work-arounds. Telecom is complicated. This is one of the work-arounds of the really stupid licensing system that we have. So you have second and third order solutions to bad primary property rights design. Spectrum, let me -- this is always a danger when you start talking about spectrum. It's even more of a danger when you talk in front of a spectrum audience. You guys can't correct me. >>: -- (off microphone) changes through team. No one can perceive these changes, what is going to change. >> MICHAEL HELLER: Let me give you a couple different points. So if you look at spectrum, you have frequencies in prime spectrums from 300 megahertz to 3 gigahertz. You have a little band that is heavily used. You have the cell phone band. You have the PCS band. But most -- okay, as I started to talk, most spectrum is just extremely little is being used. That's one dimension of use. But spectrum can be talked about in, as engineers talk about it, in at least seven different dimensions. One dimension is the amplitude of the signal. But another dimension he owe so, for example, I might have the right to broadcast at a certain 900-point something megahertz. So here is my little cell phone receiver. And there's a satellite up here. And I'm broadcasting. So that satellite owner has the right to control that frequency. But they control it nationally, but another satellite that came from, that was in a different part of the sky that broadcast from a different direction would be completely non-interfering with the first one. Because for example for direct TV, you point your, you point your satellite in one direction towards a certain part of the sky. A competing service could easily have a satellite in a different area and you could point a different satellite, a different dish in a different direction. You can actually take the same spectrum and use it again if you had a smarter way to regulate it that allowed it, that allowed directional as well as amplitude ownership. And the white spaces, the white spaces initiative leverages another dimension of spectrum. I feel like I'm going off too far into spectrum. Is this interesting? All right. Another dimension of spectrum -- I don't usually use this much blackboard. All right. Another dimension of spectrum is, you might have some, you might have some signal and below a certain amplitude it's basically, this is one piece of this. A different version, it's just noise. So the signal is up here. Certain pieces -- one of the initiatives that we have is to, it's for people who are, who can broadcast in what is now considered noise. Without interfering with the part that's considered signal. Right now you can't broadcast at all if it's somebody else's licensed spectrum. White noise, the white noise is saying when the people who are broadcasting are silent, your smart radio will switch over to that band. And use it. And one version is, as soon as they start using it again, it immediately switches over to a different one. It's basically using the, basically using the unused time which turns out to be most of the time for a lot of spectrum. There are multiple ways, there are many dimensions along which we could multiply the amount of prime spectrum that we have. And right now, we don't really do any of those, which is remarkably stupid and costly for our economy. So Microsoft and a few other corporations are involved in ways to persuade the FCC to experiment with some of these other dimensional uses of what is now dead spectrum. And technologically it's a complicated project to do. And some of the early tests haven't gone so well, but there's no reason why it won't work. It will work. It's a matter of figuring it out and a matter of figuring out how to persuade the FCC to stop being stupid on this point. >>: Working on the Microsoft problem, I worked on the orphan works problem in copyright, which is part of the gridlock problem, which says transactions don't occur because people don't have accurate information or any information about who owns what parts of a copyrighted work. >> MICHAEL HELLER: It is remarkable in this country, you literally cannot find out who owns a copyright. You can't find it out. Go on. >>: The major opponent to, and most participants in the copyrighted space think something should be done on that in terms of legislation, but the primary opponents who have been successful in stalling the regulation are individual copyright owners, like photographers and illustrators and freelance authors, who would say that the holdup frame, the last property owner who stops the transaction, they would say that's not a bug. That's a feature. That is something that actually is their defense against infringers, others who would claim a hold-up problem, but really are just users of the system and that sort of private property ownership, if you ignore that, you become unmoored for what kind of standards you use for allocating the system. The question, the larger question from what you're proposing is, how do you deal with those minority rights? And those individuals who get very worried that in the name of a utilitarian solution you are actually carving back on an important driver of ->> MICHAEL HELLER: No, I absolutely recognize that you know, this guy thinks that that's the most important copyright in the world. But just because this person thinks it's the most important doesn't mean that it's good social policy and it's a matter of choice and persuasion whether we go with, you know, this or this. So yeah, the people who own -- it's the same true in the biotech area, the pharma area. Every little biotech company says we've got the key brain receptor patented. Ours is the key. The other ones, not to important. Ours is the key. Anything that weakens our ability to sue for triple damages in an injunction for infringement of our little patent is destroying our property rights. And that is exactly what Congress' job is, is to mediate those choices between competing resource users. And if they decide that the -- part of my goal is to make clearer to people who decide that, you know, there may be a lot of these guys who are loud, but the sum of the value that is being created by these little orphan owners is negligible and the cost of not being able to find them is significant. And if that's the case, and if our patents and copyright system is predicated on the notion of creating progress and value, then you change the law. Or, that's one. Or you make it easier for these little guys to get together. Right? You create some mechanism that makes it easier for these private individuals to overcome the transaction costs and hold ups that you are now seeing. >>: Can I stop you? There are different points you made. The first one you basically said, I heard this from illustrations and everything. You say the value behalf they own is negligible, both as a political matter and -- the process of mediation, you not only insult them, you also -- you also give the other side they are opposed to arguments. You are prejudging what the value is. >> MICHAEL HELLER: Okay. >>: The second question with respect to the transaction point, to me is a much more policy neutral initiated response, which doesn't, you don't have to decide what the value is. Who knows what the value is. Some of that stuff may be very valuable. That's the problem, no one really knows the value. So I think if you focus on a transaction costs element with collection studies or other things, I think is -- (Off microphone.) >> MICHAEL HELLER: No, I mean, I say there's different kind of solutions. There's legislative choices to make and also ways to make it easier for people on their own to assemble these things. Absolutely. Before we had ASCAP and BMI, you know, really complicated to put stuff on the radio because you potentially had to license every single play of every single song. And in a sense, every sing em song was an orphan work. What ASCAP and BMI do, these are copyright collectives that mean that everybody gets paid something and, you know, some small number of people who would have gotten paid out. Some small number lose out, but as a whole you can turn the radio on and listen to music, which you could not do. You know, you can't get "China Beach" on DVD or "WKRP in Cincinnati," the old TV shows. They're just gone because ASCAP covers radio play, but doesn't cover licensing for multimedia DVDs. So we have no way to put those licenses together in the DVD context. It's really something. A lot of our culture disappears because of that. The best documentary on Martin Luther King is "Eyes On The Prize", made in '87. It's the main way that most people know who Dr. Martin Luther King is. Millions of people learned through him through this documentary, which sat in a vault for 20 years because the documentary was put together from 120 archives from video and hundreds of photos and it was all licensed for single air use and since then, for 20 years it was impossible to assemble those licenses again. So there are proposals out there for the orphan works. For example, to have you pay a dollar and if you pay a dollar, your work is registered for some period of time. So if it's worth more than a dollar to you, you can protect your work. But still, 99 percent of potential orphan works, a person wouldn't even bother paying a dollar and all of that would fall in public domain. A solution like that is politically more feasible. We say if it's worth a buck to you, here is a simple way to protect it. I think we have time for one more question. How are we doing? We're still good? We have more time? Great. Yeah. >>: I was wondering, from what you see, how much of gridlock is caused, a lot of what you say is distributed ownership, but in the case of patents, we don't know what's owned. I think that the application of a patent could be very small. It could be infinitesimal and I think it's that uncertainty that is causing -(Off microphone.) >> MICHAEL HELLER: Right. So have you guys have Mark Lemley or Carl Shapiro? These guys are lawyer economists at Stanford and Berkeley who've written a lot about economic costs from uncertainty in patents. And they call patents probabilistic property rights. With a piece of land, there's a lot of uncertainty, but you more or less can define a lot of the characteristics of land. But for a patent, its validity is at best probabilistic and its scope is probabilistic. And what, whether you're infringing is hard -- almost none of these pieces can be sorted out in the advance. So even knowing which patents to license, even if you're as diligent as possible is impossible. And many patents aren't issued, but you still may be potentially infringing. >>: (Off microphone.) >> MICHAEL HELLER: It's quantum. It's quantum and it's costly. The legal system doesn't give you the break. It gives the eventual patent owner all the presumptions. They all cut against the subsequent innovator. So it is a major flaw in our patent system. The system that allows very weak patents to be issued with very ambiguous scope, to be secret for a long time and with draconian penalties for people who infringe some things that they potentially couldn't even discover. >>: So you couldn't buy patents for ->> MICHAEL HELLER: Another way people view it is as extortion. A lot of -- no, a lot of the counsel at big, you know, at the big American Expresses and Microsofts and, you know, Sprints and Verizons, a lot of what they are doing is spending hundreds of millions of dollars buying either individual patents or portfolios of patents that they view as junk, but their patent counsel says there's 100 patents here. I can win 95 of these, but I don't know if I can win every one of them. And pay the guy $100 million have him go away. That is not productive use of scarce company resources, but it is the routine for high-tech innovators. How are we doing? One more question. Or maybe they lost -- anybody else? Yeah. Last question. >>: I just wanted to support fixes. A couple of fresh examples. I work for Microsoft -- studios. >> MICHAEL HELLER: Great. >>: We are seeing some of that evolution that you described for radio and music, occur on the interactive entertainment side. Meaning for a game, we need to sign close to, used to, have to sign close to 3 or 4,000 contracts. >> MICHAEL HELLER: For a game, you have to sign 3 or 4,000 contracts. >>: Yes, to get a game out. Now with a lot of the new titles, like Cross Band and MIPS, Guitar Hero, we are seeing those games outsell records and radio shows and concerts. >> MICHAEL HELLER: Okay. >>: So the artists and the patent holders, they come to us and they are consolidating willingly. So you see the anti-commons arrow go back to the ->> MICHAEL HELLER: You're seeing voluntary assembly in order to have -- they are having the sum of zero, 100 times zero is still zero. >>: Right. These people are coming to us and now even teleco launched their new album together on broadband ->> MICHAEL HELLER: I love this. I love these stories. I love it. >>: Aerosmith is making more money from a video game deal than from any ->> MICHAEL HELLER: Than from performing. I love it. I love it. That's great. That's the solution. I love it. Thank you guys so much. (Applause.) (End of file.)