Karen Kayekjian Bixby Program Summer 2008 Armenia

advertisement

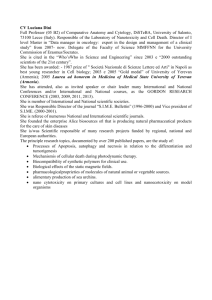

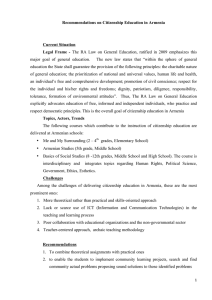

Karen Kayekjian Bixby Program Summer 2008 Armenia Context of Armenia As a post-Soviet Union Caucasus country, Armenia can be considered young and in continuous transition politically and economically. It lies south of Russia, west of Azerbaijan, north of Iran and east of Georgia and Turkey and its population seems to be around three million. Since the recent controversial election of the president that triggered a rioting uproar in Republic Square, one can feel the deep tension that lies in the hearts of many who disapprove of his supposed unlawful past. Despite the opposition that has manifested into photographs of prisoners blanketing store windows and the rows of men, women and children sleeping on the steps of Northern Avenue, the new government has gained the hopeful support of many who believe that the most recent progressive step taken foreshadows a positive future for Armenia’s healthcare system. On July 1st, the Ministry of Health (MOH) declared all deliveries and all associated costs to be free of charge and it was made public with USAID funded posters on walls of hospitals, polyclinics, medical ambulatories and health posts, television appearances of the MOH signing the decree and radio advertisements. Although introduced in 1996 for mothers, women and children, the associated Basic Benefits Package that also includes Pap smears, family planning consultations, prenatal care, contraception provision, and pubertal-reproductive examinations for adolescent girls is still not entirely covered by the government’s budget. In 2002, the Law on Reproductive Health and Abortion Rights was passed indicating that all abortions within 12 weeks of gestation are permitted and legal, an abortion after 12 weeks is legal only in the case where the mother’s well-being is in danger or the mother makes the choice based on social factors and that after an abortion, a woman receives appropriate consultation including family planning methods. The last privilege of the law is not recognized or followed in all cases of abortion. Primary and secondary healthcare were introduced in regions outside of Yerevan in 1996 and for the entire country declared free of charge in 2006. Unfortunately, the scarcity of the government health budget cannot support these changes in addition to paying for physician salaries; this dire situation clearly explains the country’s well-established informal payment system. In 1997, in order to further Karen Kayekjian Bixby Program Summer 2008 Armenia support healthcare in rural areas, the World Bank and USAID created a curriculum to train doctors in family medicine. Currently, each village of Armenia has a health post where a trained nurse offers medical consultation, makes home visits and offers referrals to specialists in town hospitals, polyclinics or medical ambulatories. In terms of family planning, consultation centers with a sufficient supply of methods were established with the financial support of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), however today, many hospitals lack the appropriate stock of oral contraceptives, IUDs and condoms. Instead, pharmacies have become a more reliable source and provider of methods for clients. More over, in 2004, USAID, Emerging Markets and Save the Children, initiated ProjectNOVA, a five year program to assess reproductive health in regions outside of Yerevan, to train ob/gyns, family doctors, midwives and nurses in family planning consultation and create and distribute informational booklets regarding FP methods, prenatal care, and postnatal care, as well as train nurses, feldshers and midwives in safe motherhood skills training. Activities As a Bixby intern in Armenia, my objective was to gain a better understanding of the context of reproductive health in the country in terms of policies and laws, relevant programs, projects and organizations, and the perceptions and practices of married men and women, mother in laws and ob/gyns. A thorough policy review revealed all the above-mentioned laws and policy changes that have occurred in Armenia within the past five to ten years. Furthermore, an extensive literature review showed studies that thus far have used a survey, focus group, intervention and assessment approach to investigate the use of modern contraception as well as the current situation of reproductive health services in rural and urban Armenia. A lack of open-ended questions and the use of focus groups instead of individual interviews in these studies may have hindered candid responses of men and women. A more in-depth qualitative study that seeked to understand the what, how and why of barriers women face when accessing, obtaining and using contraception was necessary in order to supplement existing literature and implicate more specific Karen Kayekjian Bixby Program Summer 2008 Armenia policy changes. The IRB approved study entailed in-depth interviews with married men and women of four villages surrounding Yerevan including Nor Gharberd, Oshakan, Ayntap and Tsaghkashen, as well as ob/gyns of town hospitals including Masis, Ashtarak and Etchmiadzin. We also conducted two focus groups with mother in laws of two additional nearby villages, Arindj and Parakar. Questions addressed feelings and opinions regarding family planning decisions and the promoters and inhibitors of contraception procurement. Questions for physicians addressed contraception methods and information provision to clients in the hospital. Although a more thorough and detailed analysis of transcriptions needs to be conducted, it was clear that couples of rural Armenia heavily rely on traditional methods such as withdrawal and the calendar method. There seems to be a widespread fear and anxiety about hormonal methods’ effects on the body including body hair growth and mood changes. Furthermore, only a few men out of the fifteen interviewed were motivated enough to answer questions about family planning thoughtfully. Women seemed to portray a general mistrust or lack of confidence in the medical system and along with men referenced neighbor or friend stories as reasons for not using modern contraception. Generally women interviewed had had one to two abortions during their lifetime and some had selfadministered Cytotec without the consultation of a doctor. Most women are aware of all methods of contraception with the exception of hormonal injections but are unfamiliar with the cost of methods. The handful of women who showed a general trust of medical providers were unfamiliar with the criteria of contraception methods and were willing to undergo medical tests to obtain oral contraceptives or the IUD if recommended by the physician. The responses of ob/gyns were mixed and surprising. A few physicians displayed a strong sense of knowledge regarding the explanation of contraceptives but it was unclear if that translated into the informed choice of women who are supposed to be offered more than one method option. Some physicians hardly answered questions during the interview and at times shrugged their shoulders or gave meaningless answers. The most intriguing responses from ob/gyns included beliefs that long-term oral hormonal contraceptives are unsafe for the woman’s body, OC’s should only be used for Karen Kayekjian Bixby Program Summer 2008 Armenia treatment of reproductive conditions and emergency contraception or Postinor offers less harmful side effects and is more convenient. The small-scale qualitative study shed light on some of the most prevalent ideas existing today regarding modern methods of contraception as well as offered an insight regarding family dynamics in villages. Field observations and participation in the ProjectNOVA four-day training of ob/gyns, nurses and midwives in Talin hospital highlighted the need for continuous education in the area of family planning consultation. Although providers have heard of all methods, they are unfamiliar with the contraindications, procedures of administration and general counseling techniques. The training entailed PowerPoint presentations, demonstrations of methods, role-playing and a pre and post-test to assess knowledge gained. Furthermore, interviews conducted with NGOs such as the Women’s Resource Center and For Family and Health Association highlighted organizations that focus on family planning and reproductive health awareness through sexual health courses, information pamphlets, family planning consultations and referrals. After visiting international agency regional offices, it was clear that the WHO offers technical support in the form of agenda planning and goal setting, while the UNFPA continues to provide a supply of contraceptive methods to FP consultation centers in Armenia. Despite written objectives to increase contraception use to 30% as well as increase government spending on contraception by 2015, (outlined in the Reproductive Health National Strategy, Program and Actions Timeframe 20072015), as the MOH Deputy Minister clearly explained, pregnancy, delivery, neonatal care and children’s health are currently top priority issues while contraception, STDs and infertility are less important. Challenges The institutionalized competitive atmosphere and informal payment system of Armenia posed as one of the key challenges in communicating with key players as well as gaining a clear understanding of the situation. Multiple departments, which equally served women of reproductive age, did not mutually benefit one another and lacked a common goal. NGOs and private organizations did not acknowledge Karen Kayekjian Bixby Program Summer 2008 Armenia any sort of cooperation, collaboration or connection with one another, hence making it difficult for one to find common interests between parties in order to draw conclusions about how organizations work with one another. The last comment pertains to the challenge of conducting a qualitative study in a foreign country. Conducting in-depth interviews and focus groups in close-knit rural settings such as villages requires incentives and thorough planning in order to avoid a low response rate and the loss of confidentiality.