23808 >> Amy Draves: Good afternoon. My name is... introduce Susan Cain, who is here as part of the...

23808

>> Amy Draves: Good afternoon. My name is Amy Draves. I'm here to introduce Susan Cain, who is here as part of the Microsoft Research Visiting

Speakers Series. Susan is here to today discuss her book: "Quiet, the Power of

Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking."

We all know introverts in our lives. They're the coworkers that would prefer to listen than speak, or would choose to work independently rather than participate in a group brainstorming session. The reality is that introverts are often undervalued in the current culture of American business and we lose a lot by continuing to undervalue them. Before becoming an author, Susan Cain worked as a corporate lawyer and as a negotiations consultant.

And Quiet is one of January's Amazon's best of the month, and it just hit No. 4 on the New York Times bestseller list in its first week of publication. It's her first book. Please join me in giving her a very warm welcome.

[applause].

>> Susan Cain: Thank you. Thank you everyone. Can you all hear me?

Excellent. Okay. Well, I want to talk to you today about introversion and extroversion, which I have come to believe are as profound a part of our identities as our gender.

And that therefore it's extremely important to know where we fall on the introvert extrovert spectrum. When I say this, I'm not talking about where do you appear to fall. Because in this extroverted culture of ours, we all tend to act a lot more extroverted than we really are, right? So I'm talking about who are you really, if you could spend your time exactly as you please. Your work days, your weekends, would you be more of an introvert or would you be more of an extrovert? And we're going to try to answer this question very quickly.

So what I'm going to ask you to do is just to quickly break up into groups of six, and we're going to come together and have you all share a very private, personal and profound experience from your childhood that you think illuminates who you are. And then we're going to pick the most private and most personal out of these groups and share them with the entire audience.

Yeah, right. I'm just kidding. [laughter] we're not really going to do that. But for the brief moment when you thought I was actually serious, how were you feeling and what were you thinking?

>>: No way.

>> Susan Cain: You were probably thinking like how do I get out of the room right now without insulting the speaker. Or I don't know maybe there were some of you -- were there some of you that were thinking that sounds like a nice chance to chat? [laughter].

Okay. Not so much. Well, let's just take a quick show of hands. How many of you would say you were introverts? Oh my gosh, might actually be 100 percent.

Let me ask it the other way. Any extroverts in the room?

So probably, what, maybe 4 or 5 percent of you. So the real question is: Why?

What is it that makes you an introvert? What makes you an extrovert. These are terms that I think we throw around but I don't think we really know what we mean by them. And it turns out what's at the bottom of all of this is the amount of stimulation that you like. So introverts are people who prefer lower levels of stimulation.

And I'm talking about social stimulation, but I'm talking about other kinds of stimulation in general. Generally speaking, there are exceptions. Introverts would prefer less noise, more quiet, that kind of thing.

Whereas extroverts really do truly crave more stimulation for them to feel at their best and to feel most energized. So this is why an introvert would generally socially rather have a glass of wine with a close friend as opposed to go to a party full of strangers. And you'll note when I say this that I'm giving you a social example. Because I think there's a really problematic misconception about what introversion is. We tend to equate it to the degree with being antisocial. It's not that. It's just a different way of being social. It's seeking a quieter way of being social.

But it's also as I said about other kinds of stimulation. And this is important to understand. So, for example, the psychologist Russell Geen did a study where he had people solve math problems, introverts and extroverts with different levels of ground noise playing.

What he found is that the introverts solved the problems more quickly and more effectively when the noise was lower, the background noise was lower. The extroverts performed better when the background noise was higher.

And this is a really important thing to understand, because what it's telling us is that we kind of all have sweet spots I like to call them. Sweet spots of how much stimulation we need to feel at our best. And if we can manage to set up our lives so we are living as much as possible within our sweet spots, both socially and acoustically and everything else then we'll tend to be at our most powerful.

Now, the reason I wrote this book is because for introverts it's really hard to do that. It's really hard to do that because we live in a society that is organized for extroverts. The stimulation levels are all kind of set up to maximize the energies of extroverts in general. And less so for introverts. And it may be different actually at a company like Microsoft. So I'd love to hear from you guys when we get to the Q&A at the end.

But in general, in our culture, the bias against introversion, it's so deep, and it's so profound, and we internalize it from such an early age, we don't even realize that we're doing it. But it happens young from the minute a child goes off to preschool and they're immediately presented with a group environment that

they're supposed to be plunging right into, and if they don't they sense that they're not meeting some kind of a social norm.

They know it at a very young age. And teachers have been shown to believe that the majority of teachers believe that the ideal student is an extrovert. Even though, by the way, introverted kids get better grades in general.

Same thing in many workplaces. And, again, I would love to hear your experiences here. But we are increasingly setting up our workplaces so that people have to be kind of interacting all day long and open plan offices, and when it comes to leadership, when it comes to leadership, we find that introverts are routinely passed over for leadership positions in favor of extroverts, even though recent research by Adam Grant at the Whorton School tells us that introvert leaders often deliver better outcomes than extroverts do. Deliver better outcomes.

The reason, by the way, is if they are managing proactive employees who are creative in generating their own ideas an introverted leader is much less likely to try to put their own stamp on things and instead they let other people run with their ideas and let them implement them, whereas an extroverted leader might quite unwittingly just be sort of dominant and not letting other ideas come to the fore.

Now, I also want to talk to you about kind of on a deeper and more profound level the way in which our society would be a better place and might literally depend, the survival and the thriving of our society might depend on having a real balance of power between introverts and extroverts.

And the way I'm going to show this to you at first, it's going to be -- I'm going to start in a kind of unlikely place. But I want to start by taking you with me to a colony of fruit flies. And to the animal kingdom in general.

We're going to start with fruit flies and make our way up to humans. One of the most interesting things I learned when I was researching my book is that there are animal introverts and animal extroverts throughout species throughout the animal kingdom. Who knew but it's true when you look at fruit flies, you'll find what biologists call there's sitter fruit flies and rover fruit flies. The sitter fruit flies are what they sound like. They tend to hop up and down in place. And rover fruit flies are much more exploratory, and they kind of go roaming the outer margins of fruit fly society.

And they do this for a reason. They do this because they have different survival strategies. Each one does better in each kinds of conditions. I want to illustrate this by moving a little further up the chain of the animal kingdom. I'm going to talk to you about pumpkin seed fish. This fascinating experiment that was done by an evolutionary biologist named David Sloan Wilson, who he went to this pond where he found lots of pumpkin seed fish and he dropped a gigantic trap right into the middle of the pond an event he said from the fish's perspective must have seemed as alien as a spaceship landing in the middle of Times Square.

And what happened?

What he found was that the more introverted fish sort of hovered judicially on the sidelines of the pond and didn't get anywhere near the trap that David Sloan

Wilson had put in.

And the more extroverted fish, the rover fish, they were like what's that thing in the middle of the pond? I've got to go check it out. They went swimming right up to it and they were immediately trapped.

And so had that trap been an actual predator in that scenario, it was the extroverted fish who would have perished and the introverted fish who would have survived.

But now here's the flip side. A few days later David Sloan Wilson comes back, and this time he has fishing nets and he manages to scoop up the introverted fish as well. He carries them back to his lab where the extroverted fish are already waiting for them.

He tracks what happens once they're back in their lab, and he finds that in that situation, you know an alien condition, the extroverted fish adapted much more quickly and they start eating more quickly and start roaming around and exploring and they're comfortable, which is, of course, exactly the behavior we see with human extroverts, right? They're just sort of immediately more comfortable in a new surrounding.

So in that kind of a situation, it's much better to be an extrovert, and I tell you all this at great length because you'll start to see this has parallels throughout the human condition as well.

And so now let me talk to you about humans, about sitters and rovers, about introverts and extroverts. And I want to start by talking to you about children, because children are incredibly important, because whether or not you have children of your own, the thing about kids is that they haven't yet learned to act in ways that are foreign to their true natures. So the way they act actually tells a lot about who we really are. So let me ask you: How many of you -- how many of you have kids? Okay. A lot of you. And how many of you have ever been to a kind of mommy and me or daddy and me type of Clark's music class where you all sit around?

Okay. So for those who haven't been, I'm going to show you a picture. This is what this kind of a class looks like. So it's basically, it's a bunch of parents and baby-sitters sitting in a circle with the kids, and their job is to be there singing songs and playing musical instruments.

What you find when you go to a class like this, you find that half of the kids, roughly, are behaving like sitters, meaning that they are cleaving to their parents' laps, they're not going to explore, they're watching from the sidelines and the other half are exploring as if there's nothing in their way.

Like that little kid, do you see that baby in the red jumpsuit, he's right there in the middle of the room. He has no idea where his mom is. And that's okay with him.

Now, the thing about these kinds of classes is I know from years of researching of interviewing parents that the parents of the sitter children tend to get really worried about their children, because they feel like oh my gosh this mommy and me class, it's symbolic of what's going to become of my child the rest of his or her life. They're going to sit on the sidelines. They're not going to participate. No one is going to know who they are, they're not going to get the best that this world has to offer. And they really worry.

So let's track the development of these two kinds of children to see whether this worry is warranted. Now, the rover children -- I think we already kind of know what their development is. They tend to be very bold, very exploratory. These are kids who will make friends very easily when they grow older it will be easier for them to strike up new business deals.

You kind of know the picture. The children who are more on the sidelines, here's the important thing to understand about them: It seems as if they're just sitting there kind of passively and inertly, but that's not actually what's happening.

These children are doing what psychologists call paying alert attention to things.

They're paying alert attention. And so very often they will ultimately plunge into whatever the social scenario is and sometimes it takes them minutes and sometimes it's days or weeks or months. But they will plunge in eventually, and when they do, they understand the rules of the game. And they usually understand it with a kind of subtlety that's born of this kind of close attention.

And so the thing about these children is that they're noticing scary things, but they're also noticing more things in general. And I'm just going to give you an example of how this plays out cognitively and intellectually because these children do have a different intellectual way of interacting with the world.

If you give this kind of kid a type of game, two pictures that look very similar and the job is to just spot the subtle differences between them, these children will spend more time figuring out the difference between the two pictures and they will more often get the right answer. And this is true all the way into adulthood.

Once these children grow up, if you give them problems to solve, they will spend more time at the problems and they will more often get the right answer.

And one example of this is somebody like an Einstein who famously said it's not that I'm so smart it's just that I stick with problems longer. And this really is a very effective style. And so introverts, as I said before, they've been shown to get better grades. They more often get, have phi beta kappa keys. They do well intellectually in general.

I'm sorry extroverts but introverts they know more about many subjects than extroverts do. There was one interesting study where they tested college freshmen in 21 different subjects. Ranging from art to astronomy to physics to

statistics and the introverts knew more than the extroverts of every single one of the subjects.

And what's important about this is that it's not that the introverts were more intelligent, because as a group the introverts and extroverts are equal when it comes to IQ scores. It has nothing to do with intelligence. It's, rather, that the very behavioral style that our culture excoriates in introverts is actually a boon when it comes time to sitting down and solving problems and strategizing and thinking things through. It leads to a kind of quiet persistence that can take you very far.

Second difference between these two kids, these two kinds of kids that I was telling you about. They have very profoundly different orientations to risk. I didn't know this when I started doing my research. It was kind of news to me. But introverts approach risk in a much more circumspect way than extroverts do.

Extroverts are more likely when they see something they want their mode is to just kind of orient themselves to the goal and just go for it.

And this is actually a neuro chemical difference. Extroverts have stronger reward networks in their brain when they see something that they desire whether it's a promotion or business deal or whatever it happens to be, they get really excited, and they start having very joyous physi emotions. They're quite delightful. I think it's because of these emotions that the extroverts enjoy the admiration they do.

It's a champagne quality. That's lovely.

But the down side of these emotions that I don't think we pay attention to is when you're in this kind of state of orienting to a goal you literally don't see as much warning signals that are standing in your way. You just don't see them.

This has been shown in the lab. So introverts are much more likely to be able to see the warning signs. And this is why, if you're a group or if you're an organization, you really need to make sure that you are equally honoring structurally both types of people, because you need both of these viewpoints.

Extroverts more likely to get in car accidents, more likely to place financial bets and more likely to participate in extreme sports. But what I want to say here is that it's not that introverts don't take risks at all. It's not that at all. And in fact a study of a London Investment Bank found that the most proficient traders, most successful were introverts. Warren Buffet is a perfect example of this. He's a self-described introvert. His MO is to carefully analytically take the measure of an entire situation warning signs and all. So it's not an accident that he is famously admired for having sat out the two gigantic bubbles of the past years, the tech bubble and the housing market crash. Warren Buffet was not participating in them. That's characteristic behavior.

Okay. And I do want to say, by the way, about this, I think that the issue that we have in our culture in general is we lion-ice too much the attitude that celebrates wrist taking at all cost, the seizing the day attitude.

I saw this myself when I was a Wall Street lawyer. I practiced Wall Street back in the '90s. This was during, of course, some of the go-go times. And at the time I heard a story that was circulating on Wall Street about a group of bankers who were pitching for some new business.

And they wanted to distinguish themselves from the other bankers that were competing. And so what they did is they came into the pitch room. All of them dressed in matching uniforms. And on the matching uniforms were written the three letters FUD. And FUD stood for fear, uncertainty and doubt. And they had a big X through the FUD. And so their message to their potential clients was you come with us and you will have no fear. You will have no uncertainty. You will have doubt.

And I would argue that it's that kind of attitude and the lionization of that kind of attitude that has led to some of the problems that we've seen, and so we need much more of a balance between the two orientations.

Okay. Running out of time. So I'm going to tell you about one, a third thing that distinguishes these children I was just telling you about. And that is creativity.

That's creativity.

Studies have shown us that the most spectacularly creative people in a wide variety of fields have tended to be introverts. Not just any introverts. They're introverts who also have a social component to them.

So they're people who are comfortable exchanging ideas and they're comfortable advancing ideas. But they also have the need to kind of go off by themselves and focus on the thing they're doing. And this is important, because we can all learn from this.

These introverts, they're not necessarily -- it's not that they have some intrinsic magic button that they press that makes them more creative, it's, rather, that solitude turns out to be a crucial ingredient to creativity. We're living in a culture right now that's telling us that the answer to creativity is to bring people together in groups and to be functioning in groups.

But introverts are people who will go off by themselves and do what they need to do. And this is not to say that groups don't have an important place in any kind of creative or productive measure. But the truth is when you are in a group of people, literally you can't think in the same way you would independently.

It turns out that we're such social creatures, all of us, introverts included, we're such social creatures that if we're with a group, we instinctively mimic the opinions of the people in the group without realizing we are doing it.

So even something as seemingly private and visceral as to who you're attracted to, if I show you pictures of faces and I ask you to rate how attractive they are if you're in a group of people you'll start literally responding in your brain with more attraction towards the faces of people who your fellow group members have already deemed attractive. As I'm saying this, this is not something that we can

control. It's not something we're doing because we want to fit in, it's just something that happens.

The other thing that can be dangerous about groups is that years of social psychology experiments tell us that when you come together in a group of people. Invariably, the person who speaks the most effectively, the person most assertive or dominant that person's ideas end up getting listened to the most.

I think we've all had this experience in our day-to-day lives but the thing you may not know is there's a whole other raft of studies that have found that there is zero correlation. Zero correlation between being the best talker and having the best ideas.

So that person who is gaining the attention in a room may have the best ideas, but they may not. And so if you are charged with figuring out what the best brains in your organization have to say about whatever question it is, and your answer is to gather people into a room and see what everybody says, you're probably not going to get the best ideas.

So you need to come up with other ways to do it, ways that honor the solitary thinking process as well together with a group one.

So having said all this, I do want to be really clear about what I'm not saying. I'm not saying that man is an island after all and that we should all just go off by ourselves and never talk to each other again. That's not the point.

We are human beings, and we love each other and we need each other. And life is meaningless without love. And it's meaningless without trust and without friendship. And I'm also not saying that we should abolish group work altogether or teamwork all together. This is especially true today we can't do it because the problems we need to solve are so complex that we can't solve them literally without standing on each other's shoulders and working together to some degree. But I'm saying human nature really -- it has two competing pulls, and there's one pull that has us longing to be with each other and there's one pull that has us craving privacy and craving solitude and craving autonomy, and we need to figure out ways of fueling both of these drives in order to have everybody functioning at their best. And this is true of everybody, true of introverts in particular, but it's true to some degree of us all.

So I just want to leave you with three thoughts, and then I want to open this up to

Q&A and hear what you have to say. I'm going to leave you three kinds of calls to action. The first one is I hope that you will all just make more time to sit still and be quiet and think and be yourselves without feeling guilty about it.

The primary thing I found when I was doing my research is that people feel guilty about wanting to go off by themselves, because it has been so instilled in us that this is a bad negative antisocial thing to do and it's just not.

Second thing is we need to honor the next generation of quiet children. You know, the kids who are sitting on their parents's lapse in the mommy and me

case. The kids who, when they're teenagers, develop deep passions for spider taxonomy or 19th century art want to go off by themselves and pursue those passions, those kids should be honored and not made to feel weird, these kinds of talents and orientations should be cultivated.

And then finally I want to kind of come back to where we started. And I want to ask you to think again in private, not in a group, about who you really are and what makes you feel powerful and what made you feel powerful when you were a child. We all know from the lessons of myths and from the lessons of fairytales that there are many different kinds of powers that are available to us in this world.

This is what myths tell us. Luke Skywalker is granted a light saber with which to swashbuckle his way through the galaxies and Harry Potter gets a wizard's education but there are some quiet kids the power they're grand is a key to a secret garden that is full of inner private riches and that's a power, too.

So the trick for all children now for all of us now that we're grown up, the trick is to use whatever power we've been granted and to use it as best we can. And so that is what I wish for you all. Whether you have been given a light saber or whether you have been given a key to a private garden. I hope that you will use the power you've been given, and I wish you all the best with it. And thank you very much. [applause]. Now what I would love to do, we have some time, I'd love to hear your questions. You can ask me anything. Yes?

>>: Did you do any research relative to virtual collaboration where you're not actually in a room together?

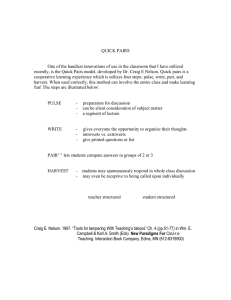

>> Susan Cain: Yes, this is such a good question. Really interesting. So there's all this research on in-person brainstorming. 40 years worth of research literally that finds in-person brainstorming is a disaster and individuals always do better than groups.

But the one exception to this is when groups brainstorm electronically. And it's not that the reason that electronic brainstorming or collaboration works is because it removes a lot of the social barriers that exist when you come together with a group of people.

You know, there's a number of these barriers, like one of them is just if you're in a group of people in the same room all participating at the same time, really only one person can think at the same time. One person's talking, one person's thinking, everybody else is oriented to what that person is saying. When you're working kind of asynchronously in an online group, that is removed.

Then the other thing is it turns out, if you are in a group of people, face to face and one person dissents from what the group says, that person has been found by the neuroscientist Gregory Burns at Emory University, he found that the amygdala, the small organ in our brain associated with the fear of social rejection, that the amygdala in your brain gets very activated at the moment you're dissenting. He calls this the pain of independence. He said this is what's wrong with some of our jury trials, for example, you've got people in a room and

it's painful to dissent. But when you're working collaboratively a lot of that problem is removed. I'm sorry, when you're working electronically.

>>: Thanks a lot for this talk. It's very interesting.

>> Susan Cain: You're welcome.

>>: Sheds light on this. [inaudible] the question is shifting more into within a day or within a month, right? So seem to be categories, two separate things. I think what I am by nature and what I am by habit. There's a mixture [inaudible].

>> Susan Cain: Yeah, thank you. That's an important question. So a couple of things about that. For one thing, introversion and extroversion is really a spectrum and we all follow different parts along the spectrum. But even for those who fall at one extreme or the other we all still have aspects at the other side of us. This is not a black and white thing. I'm talking about it in black and white terms to make a broad point to you but we are, of course, all kind of a glorious

Michigan mash of glorious traits. What you're getting at our traits can change a little they can change to some extent over time depending on how we spend our day-to-day lives.

For example, an introvert who is not comfortable going to cocktail parties but who goes to them day after day after day will probably over time get more comfortable but they'll still be an introvert. And it sounds like you're having an opposite experience.

Yes?

>>: Have you done any studies around the relationship between being an introvert and having anxiety?

>> Susan Cain: Yeah, also an important question. Are you talking about social anxiety or just general anxiety?

>>: Good question. A little bit of both. But I'm just, let's go with social anxiety.

>> Susan Cain: Okay. Yeah. So this is interesting, because culturally we tend to think of introversion and shyness as being pretty much the same thing.

In fact, they're quite different. Introversion is just as I was saying, the preference for lower stimulation environments, and shyness is much more about a fear of social judgments.

And the two do overlap, but psychologists debate to what degree they overlap.

>>: I have two questions, one was what surprised you the most in your research?

The other one was more like I kind of have this theory in my head a long time I can be social and I can appear like an extrovert in some situations but when I go home at night I want to be home alone after a day of socializing. So I often think about how much introverts maybe don't -- it isn't they don't want to be extroverts,

it's maybe they don't have the right set of people to stimulate them. Because I see a certain sense of people when you get them with their best friend they all of a sudden get super social. How much is it they're truly introverted people or they're just not with the right set of people to make them to raise their stimulus levels.

>> Susan Cain: These are tricky questions. And Carl Young, the first psychologist to popularize the terms introvert and extrovert back in the 1920s he talks what you're saying, how if you get an introvert with the right group of people, the way he puts it, he will relax into being an extrovert. So then the question is, well, does that mean he's really an extrovert as long as he's with the right group of people, or is that actually characteristic of an introvert that they become outward only in more limited circumstances whereas with an extrovert they'll come outward no matter what.

And then for your question about what surprised me the most. I don't know if this is what surprised me but it struck me. I have a lot of profiles in my book about introverted leaders. And this was very important to me, because there's such a deep-seeded notion, I think, that there really is only one way to be a good leader.

I think we think of leaders as being very bold and very charismatic types of figures, but I saw -- but in my book I profiled a number of transformative leaders over time people like Rosa Parks and Gandhi and Eleanor Roosevelt and people in the business world, too.

One thing you find with these leaders is that the reason they're as effective as they are is precisely because they don't like the spotlight. So if you don't like the spotlight but you're really motivated by a cause or you're really motivated to serve your organization well, that's a kind of pure motive. And the people who you're asking to follow you sense it's purity and they sense you're not motivated by narcissism, and that can be a real power of its own.

And Jim Collins, who is the famous management researcher who wrote the book

Good to Great, he did this famous study where he identified the 11 top-performing companies of a particular period of time. He tried to figure out what it was that distinguished these companies. Why these 11? Why had they risen to the top? And initially he didn't want to look at leadership at all, because he thought that that would be too easy an answer, too glib an answer.

But what he started to notice, he and his team, was that every single one of the leaders of these companies, every single one of them, they were all people who were described by their employees with a certain kind of constellation of traits.

Shy. Humble. Self-efacing. Modest, this kind of thing. And they were also people who are great will and great visions for their companies.

And he came to call this combination of traits level five leadership, which led to this kind of funny scenario of he would go out and present this to groups of quite alpha type A leaders, and they would raise their hands and say how can I become more of a level five leader? How can I become more shy and unassuming. Not so easy.

Amy?

>>: I have a question. One is it seems like social networks like Facebook empower introverts, is there any research about that?

>> Susan Cain: Yeah, there is. And, of course, like with anything else with the

Internet it's changing all the time.

So historically in Internet times, the Internet has been a place where introverts have been empowered, and in fact a poll done by social, by Matchable, the social media website, found that most of its users were introverts as by the way Pete

Cashmore who started it. And another study introverts said they felt they could express the real me online in ways that they couldn't do in person.

All of which makes perfect sense, right? But now it's starting to fragment more and we're starting to see the mainstream social media sites, in particular

Facebook, have become more havens for extroverts. So introverts use them but not quite as much or with the same glee.

And that's not so surprising when you think about it, because so much of

Facebook is about a kind of self-presentation and how many friends do you have and this kind of thing.

What I've observed anecdotally introverts like more of a site like a live journal where you're doing more long in depth diaries, sharing them with a select group of people or blogging where it's really about your thoughts that you're presenting in depth, that kind of thing.

>>: Your research about what drives people to make friendship and partnership choices based on their extroversion and introversion -- my wife, for example, extreme introvert and I'm not. And I know that's pretty common.

>> Susan Cain: It is.

>>: For a lot of people. I'm wondering why that might be.

>> Susan Cain: It seems to be there's really a kind of mutual attraction. So in marriages the statistic is about 50 percent that half the marriages are introvert/extrovert marriages. And I'm in that kind of marriage, too. I'm an introvert and my husband is an extrovert.

And it happens, though, also even at the level of teams at work, it's been found that the most effective teams in organizations tend to be a mix of introverts and extroverts, because the two types are just drawn to each other. I think we all know yin and yang when we see it. We all know that they're traits of ours that we neat to complement. We have our strengths and then things we're not so good at. So that's really what lies at the heart of many of these friendships, too.

In social relationships, it's been found that what happens is introverts when they're around extroverts, they feel that the extroverts bring out their more carefree side. They feel more up and more alive and more light when they're with an extrovert. And extroverts on the other hand appreciate introverts because the introverts allow them to talk about more serious things that they might otherwise not think to go to or might feel uncomfortable going to. But I should say, too, this really is true also at the highest levels of leadership. If you look at many leaders, you will see them -- effective leaders, you'll see them trying to complement their own strengths.

I was thinking about this yesterday. I'm reading the book the Obamas by Jody

Kanter all about the Obama Administration. And I believe President Obama is an introvert. It's fascinating to see, I don't know if it's delivered or not, but how much he's always choosing partners who can complement his introverted tendencies.

So Michelle Obama is a real extrovert. She's very often the one who is urging him to connect more directly with his audiences. And he chose his first chief of staff Rahm Emanuel who is more combative than he is because Obama is famously not a combative person, like many introverts. And Joe Biden as his running mate. That's a perfect example. Joe Biden is the type of politician who loves to go out and do the glad handing, back slapping kind of thing that

Washingtonian politicians do that Obama doesn't do naturally. That's one example but there are many I can give you.

>>: The perception that society rewards extroverts is pretty pervasive. It's funny, because if you look at pumpkin seed fish or look at fruit flies, they don't reward extroversion and introversion. It's kind of ridiculous on its face, because those creatures don't have the complex social structure we do. They don't do things like send their kids to school, to working groups, have big companies where there are a few leaders that tend to be extroverted, and they haven't had moments in history like the industrial revolution where people started living more closely together in big cities.

Of all those kinds of things, what do you think are the biggest reasons that society rewards extroverts?

>>: Can I add a question to that, because we talk about society, we've been talking about biology, are you talking about American society or is this global or more introvert-ready cultures?

>> Susan Cain: That's an important question. It was one of the first things I looked at when I started my research, because I was really trying to figure out, is this preference for extroversion somehow innate to humanity or does it vary across cultures. And I really found quite a difference from culture to culture.

And particularly I focused on far eastern cultures where there's actually a branch of psychology called cross-cultural psychology and psychologists study this quite a bit.

There's more, particularly in the Confusion belt cultures of the Far East, there's much more reverence for silence and for reserve and the person who doesn't speak so much is often seen as being wise and very judicious.

And words themselves are perceived as being potentially dangerous, because words can hurt other people. Words can hurt the person who uttered them, if you say the wrong thing at the wrong time. So they're really quite different attitudes.

And in fact there's one study that compared Chinese school children with

Canadian school children, and they found that among the Chinese school children, the students who were either quiet or shy were often admired by their peers, and seen by their teachers as great candidates for leadership positions.

And in Canada, of course, the exact opposite thing was true.

But depending on your perspective, the thing that is said this is starting to change and they repeated this study recently and got quite different results with the things in the Chinese school yard being much more similar to what's happening in the west, because these attitudes are starting to shift, just the way western

McDonald's is being exported globally, the same thing is true of our sense of the ideal self.

>>: Going back to the corporate social interaction, if you're sitting in a room with

12 and two are introverts and 10 extroverts, how do you give pressure to that team to get that team not to isolate and be biased against the quiet people in the room?

>> Susan Cain: Good question, I believe that these changes have to come about mostly structurally, if you're talking about at work.

I don't think it's really going to work to say, okay, assertive people remember to pay attention to the less assertive ones. So instead thinking about structures that work, for example, saying before a meeting we're going to distribute the agenda of the meeting in advance so that everybody can prepare. Because one of the primary things introverts complain about in meetings is that the meeting is going quickly and they tend not to think as fast like that. They're not thinking on their feet.

They often feel like I thought of the thing I wanted to say but by then the meeting was over.

>>: But the reward structure is, go into that 15 or 30-minute meeting get the gist of the idea A, B, C, this is what we're going to do how we're going to move forward, the reward structure is clearly, or feels clearly set for the extrovert. And so the question is that from a personal action plan like you said I'm sitting in two of 12, how do I manage myself into a different place.

>> Susan Cain: Gotcha. Right. Yes. Okay. What are some things that introverts can do when they're in that setting. Did everyone hear that question?

What can introverts do when they're in a meeting and they feel like they're sort of outnumbered by extroverts who are communicating with a different style. The

trick with all this stuff is to figure out how to use your own self in a way that is strong.

So, for example, it might be you prepare before the meeting even if nobody else has and you have your ideas that you want to get across. And making sure to state your ideas pretty early on in the meeting is helpful, because research shows that we tend to pay more attention to the ideas that are advanced quickly or advanced early.

And then there are things like if the idea that you're advancing, if you feel conviction about it, you don't necessarily need to say it in the loudest voice for people to feel your conviction. So the key is kind of testing your ideas beforehand to know how much you really believe in them.

If you do, just making sure to get them out there. Another role that introverts can play very effectively is being the person who asks the thoughtful questions that redirect the group into a -- into a place that makes sense. Because we've all been in those meetings where like you're off talking about God knows what and everyone realizes you're off on a tangent. The person who gets you all back to where you're going ends up getting a lot of power in the room.

>>: One of the things that I received from the person who organized this meeting is that to connect with the people that are going to be [inaudible] as much as possible. So that the people would know who you are and what kind of meeting we would have.

>> Susan Cain: That's a good idea. And for many introverts that's much more comfortable, right? Instead of trying to forge bonds with ten people at once in a meeting, which usually requires just playing a dominant role so that everybody knows who you are. It can be much more comfortable and effective to just build these alliances, kind of one-on-one, behind the scenes, before the meeting happens, but also after. That's another thing. After the meeting, you might be the one who actually takes the ten minutes to sit down and think about what did we just say here. What are the ways that I can build on what was just said and maybe you sent out a memo that summarizes things and advances the ball. So it's like if you're comfortable more with writing than with speaking, use that. And make the most of it.

Amy?

>>: Does your research show any data about how introverts and extroverts handle stress?

>> Susan Cain: How they handle stress? Interesting. I would say introverts who tend to be on the anxious side of the spectrum, I was saying some are and some aren't, they probably suffer stress a little bit more and need to pay attention to stress management techniques more than a nonanxious extrovert would. But I haven't seen a great deal of data on that.

>>: Second question, sort of similar. Which was it seems like a lot of celebrity musicians, sports figures, self-describe as introvert but [inaudible] scale performance, any research discuss this [inaudible].

>> Susan Cain: This is a fascinating subset of introverts. I met a lot of these people in my research. I don't know if you all heard the question but Amy's basically asking about the phenomenon of introverted performers who seem to thrive on public performance but describe themselves as introverts and how can this be? And I was fascinated by these people, and I interviewed them. And what they told me is that they tend to experience the audience as just one unit.

So they're not feeling intimidated by speaking or performing for 100 people at once. They feel like they're just having a conversation with one person.

And they also tend to feel that they're more comfortable in that kind of a setting than they are just chatting one-on-one, because they feel like it's a situation where they can totally control what's happening. And that they're kind of appearing behind a mask to some extent. Because we've all had that sensation when you go to a costume party and you're wearing, you have a mask on or you've got your costume. You can often feel more liberated than you would if you were just going as yourself. And this is the way actors often describe their craft.

I think we probably have time for one more question.

>>: I just wonder, follow up the question Amy just asked. Just wondered, do we have a clear and universal and all people agree what's the definition of the introvert and extrovert, because seems like the one who can speak loudly on the large audience, are these people really introvert, I was curious do we really have such a classifier that can be universal, even like culture-wise, you mentioned in

China, for example, if the different ranking system, different culture, maybe is different standard when you classify as introvert or extrovert in China or U.S. So do we have such a standard for the introvert or extrovert?

>> Susan Cain: No, it's a good question. I like to say that there are as many definitions of introversion and extroversion as there are personality psychologists. They all -- every psychologist has hills or her own definition.

They all kind of argue about it.

The one thing they do all agree on is that whatever introversion and extroversion are, they know they're important. They all agree that it's pretty much the most salient aspect of human nature, and that this is true across all cultures. So the best -- so I looked at sort of the primary of all these definitions. The one I thought was most representative of all, that most would agree on, is what I told you about stimulation. I think another way to think about it is where do you get your energy from? Do you feel, when you've been out socializing, maybe you've had a really good time, but still do you feel like now you need to recharge at home or in solitude, or do you feel like you're now all energized and you want more socializing, that in some ways is a real key distinction. Okay. So I think we could probably keep going, but I'm going to have to catch a plane at some point. So I

want to thank you so much, and I'm going to be at the back to sign your books if you would be interested, and you've been a wonderful audience. So thank you, thank you, thank you. [applause]