>> Debra Carnegie: Hi, everyone. Thanks for coming. ... Debra Carnegie, and I'm pleased to welcome Dr. Karie Willyerd...

advertisement

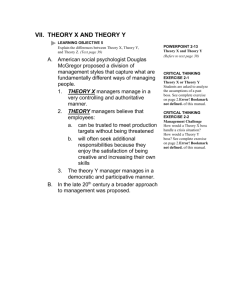

>> Debra Carnegie: Hi, everyone. Thanks for coming. My name's Debra Carnegie, and I'm pleased to welcome Dr. Karie Willyerd to the Microsoft Research Visiting Speaker Series. She's here to discuss her book, Stretch, in which she helps us to anticipate the needs of tomorrow's work environment. Karie is the workplace futurist at SuccessFactors and has been the chief learning officer at several Fortune 500 companies. As a writer, she coauthored the bestseller The 2020 Workplace and blogs regularly for the Harvard Business Review. Please join me in giving her a warm welcome. [applause] >> Karie Willyerd: Thanks. So small audience here, although I know there's more on the line. So I'm just going to share a little bit of personal. I turned down my first job offer at Microsoft in 1987. Bad move. When people ask me what the worst decision I ever made was, I said, well, I think that maybe that one was it. 1987 would have been a good time to come in. 2010 was my second job offer from Microsoft, and I decided at 50-plus that I had an entrepreneurial bug, so I just finished working for Sun Microsystems. I was the chief learning officer for Sun Microsystems. Ran Java certifications around the world, so I had like 1200 people working for me, and decided to create a social platform that people could learn from one another. We named it Jambok, and in 11 months it was acquired by SAP SuccessFactors. So it's now the product SAP Jam. So that's how I worked for SAP. And you never know how your career is going to morph, because I'd always been a big company person and then I went off and did an entrepreneurial gig and then back in. And so that's a little bit of what inspired my story about Stretch. But there were a few other things that inspired it. One was a conversation with a guy named Michael. And I know I called him something else in the book, so you'll see who he is in the book after I tell his story. But I met him in Australia. We were sharing the dais together. And he seemed like a really interesting person. We went to have cocktails together at the event happy hour, and it turns out that he had started as a journalist. So he worked for several newspapers, ended up in San Francisco. But he had worked in Japan, he'd worked in China. He'd worked in a number of locations, so he really had prepared himself globally to be a journalist. He had one won Pulitzer Prize and had been nominated for two more. So somebody that you would almost think as kind of bulletproof in a career. Well, he got a new boss, and the boss said I'd really like to know how you're promoting your stuff on social media. Well, if you're an old-school journalist, that sounds a little bit like just being a -- somebody out on the street selling newspapers. It just doesn't feel like the -- what you were raised to be as a journalist; that that's somebody else's job to go sell newspapers. So she asked again, and he just kind of resisted. And the third time was a pink slip. So he had kids in college. He was in his early 50s, he had kids in college, and he had promised them he would send them to school. So he remembers going out to the car and smelling the new car smell, because he had just bought a car as well, he just completely was unprepared, and was a Chevy and had 4G connectivity. So he was looking to see what right off the bat what can I do. And he just realized he was going to have to make himself over. So he went to work for -- there's no reason not to say the name of the company. He went to work for McKinsey as a consultant. And they really liked his global background and his ability to communicate. But he was really into telling people the truth about what he saw, just like you do as a journalist. You write the truth. So when he went in to talk to clients and share what the findings were, he would be very openly honest, transparent, and truthful. Which is a good thing, but he didn't tone it down in a way that people could hear. So 18 months later he had his second pink slip. So there's one thing that can motivate you -- it's a couple of pink slips with two kids in college within a two-year period. So then finally he decided, okay, the world has shifted; I need to shift with the world. And when I met him, he was now seven years into a career with another consulting firm, a really fantastic consulting firm based in the U.K., and he had made this shift. He was -- you know, you can find him on Twitter, you can see what he's doing in LinkedIn where he's posting and how he is connecting with clients. So that seems like nothing to us, those of us who might be under 30. And I'm not in that category. It might not seem like anything. But for some people it's a really big shift. And so, you know, so stories like that kind of motivated me and my coauthor to really think through some things. So let me tell you just a little bit about some of the research. This is one of the research questions we asked. So I'm just going to ask you to raise your hands to each of the answers. The first one is going to be, we asked: What concerns you most about your future? Wage stagnation, economic uncertainty, not enough opportunities for advancement, your position changing or becoming obsolete, or inadequate staffing levels? Let's see how close you are to kind of the global average. I would expect you wouldn't be identical. But how many say wage stagnation? Okay. We've only got one or two hands in the room. Economic uncertainty? Okay. That looks like about 20 percent of the room. Not enough opportunities for advancement? Well, that might be a third of the room. Position changing or becoming obsolete? That's maybe half the room, a third to half. And then inadequate staffing levels? And that's a few hands, just for the online audience so they can hear it. So here's what we found in our survey. The number one choice was position changing or becoming obsolete, and that was higher in the U.S. than in other places. And then secondly was this not enough opportunities for advancement, which looks like pretty much what happened in this room, too, in terms of the same kind of thing. So people are worried about becoming obsolete. Our survey was done with Oxford economics, it was in 27 countries, half -- twin surveys, actually -- one for executives; one for employees. And we were asking them forward-thinking questions about where the world was headed. We also -- when I say "we," my coauthor, somebody I did my doctorate with. I got my doctorate at 50, and she was younger. She'll never let me tell how old she was when she got it. So we reviewed over a thousand academic papers, kind of looking at how do people stay current, what is it that people do to ensure they can keep up with work. And the reason we called the book Stretch is because it's not great big gigantic leaps that you take, it's incremental steps that you take all the time to stretch, to stay current. And so, you know, we just did -- once we developed five practices for how you stay current, how you avoid becoming obsolete, then we validated those by talking to dozens of chief learning officers, because that's kind of the little niche of jobs that I came out of. Just one quick slide to kind of set the stage for what are the practices that you use to stretch. They're an enormous amount of trends underway. I'm just going to show you just a couple. But one study that was done by Oxford University -- just coincidental that it's by Oxford University -- says that 40 -what they did was they looked at 702 job descriptions in the United States and determined on each job description these are the ones that are in the bureau -- the Department of Labor database -- what part of those jobs are going to be subject to computerization. And they determined -- what percent do you think they came up with are highly likely in the next decade? Just throw out a number. >>: 10 percent. >> Karie Willyerd: >>: 90. >> Karie Willyerd: >>: 10? 90? 60. >> Karie Willyerd: 60? It's 47 are highly likely. 47 percent are highly likely to be computerized within the next decade. 19 percent of medium likelihood. And it's not all of the jobs that we think. So I'm going to use the word robot to talk about computerization. And by robot I'm going to mean algorithm or whatever it might -- so there's just -- and there's also these huge demographic shifts on globalization that are -- that's happening. Here I am talking to you in Seattle. I work from my home in Colorado. My local headquarters is actually San Francisco. And it's a German company. And on every call I've got people from all over the world, as I'm sure you do. In the United States, 11,000 people a day are turning 65. Just a couple years ago it was 10,000 a day. Now we're hitting the maximum of the baby boomers who are starting to turn 65. People are starting to work older. I've met personally six people who were over a hundred and working. The oldest I've interviewed was a 106. And even she was thinking about what am I going to do next. You know? She wanted to -- so, you know, so people are working longer. Because they get meaning and fulfillment out of work. It's not -- none of those six that I met had to work because they needed the money. The money was kind of incidental. It was more their social setting and how they found -- made purpose in their life. And we have kind of a small generation behind it, Gen X. It's smaller because in the '60s birth control is introduced and women go back to work. The average age women had their first baby went up by 7.1 years. And so we just have a smaller Gen X and then a great big millennial generation behind it. So as we have baby boomers who -- as they exit companies and start to do other things, you know, like I did, I got a nice poison pill from Sun so I could go and start a company and do something really different, I think a lot of baby boomers are going to make that choice too, to do other things, leaving behind a lot of opportunities for people to really fill that void. And so at the -- I kind of agree. Even though my message is the world is shifting and there's going to be a lot of automation that's going to replace much of the work we're doing, McKinsey approaches it from saying it's not necessarily that jobs are going away, but part of our jobs are going away. Even the part of a job of a CEO. 20 percent of their work they think is going away; that it won't be -- that a CEO can go out and say, hey, I've got an idea about what company we should go buy. It's going to have to be supported by data from some kind of algorithm that's calculating in the background the sensibility of that acquisition. So we're going to have a lot of changes underway, but I do agree with something that John F. Kennedy said, which was -- I'm paraphrasing -- if we're smart enough to invent technology that replaces people, we're smart enough to invent new jobs for people to fill. And so I think that's the case as well. But it does mean that we'll have to shift and morph with it. Here's a hotel in Japan that is almost fully run by robots. Now, Japan is kind of unique because the average age is moving up and up and up. So one-third of people in Japan are estimated will be 85 by the year 2030. They live longer than most of -- so we're going to have, you know, a really old -- I'm sorry, older than 75 in 2030. And not a replacement population coming in place, a very crowded nation. And so they don't have a lot of immigration into Japan. So they're looking to replace it with robotics. And so you have -- you can check in here, and you can have this Actroid on the lower left-hand corner, who greets you. She's got natural language processing software built in. So her expressions change to move along with you. That creeps out a lot of people, so then they want to just go see the Velociraptor instead. So they go over to check in with a Velociraptor. They have little trollies that take your luggage up to the room that are just -- you know, they just plug in where to take it. That's your room service and everything as well. Here's one of my favorite, and I hope this will project for people. Here's one of my -- whoops. Let me get this going here. One of my favorite inventions that I hope is true. They say this will be ready in 2017. So crowdsourcing recipes so that you've got your -- this isn't the Jetson version of the robot in the kitchen. Once something is loaded in the database, you just load it into the computer here. Set up the ingredients for the robot. This was at the computer -- I mean the consumer electronic show in Asia a few weeks ago. And it cleans up. So, you know, we think of robots be able to complete these kinds of things. But when you think of it, it's just an algorithm. Here on the screen I've got two sports stories from a Texas high school baseball team. One was written by an algorithm, one was written by a human. Which one is which? Okay. Give you a chance to just look it over. How many people think a robot wrote the first one? About half the room. How many people think a robot wrote the second one? It is the first one. So here we are split half and half in the room. We can't tell the difference. It's estimated that -- and this company is called Narrative Science. It's estimated that 90 percent of the news could be written by robots by 2030. Now, if robots can write news, of course they're already doing financial reporting and medical diagnosis. I started a second company while I worked for SAP. The difference in that four years between those two companies was really dramatic in terms of how software got developed. In the second time around we were going and getting joules of content and pulling it in to assemble a software program. So, so much more of that is even becoming automated. A lot of legal research is already done by algorithms that are going out and looking at as well as market research, call centers. So I think what it's going to mean for the future is that we're going to have to think about reinventing our own business models, how -- how to -- and I don't think it means for the prepared that it means we're out of jobs. I think for the prepared it means that we're just shifting in terms of how we work and what and who we're working with. And it means, I believe, stretching each day. So just a little bit. If we do just a little bit all the time to get ready for tomorrow, then I think we can be ready. So when we talk to people, as what we were trying to find out what are the -what's the context in which people are working, so we had write-in comments from 5,500 people and we interviewed hundreds. And one of the number one things we heard was, you know, it's pretty much all on me to manage my career. As someone I heard said, nobody cares more about your career than you do. And I was at a CHRO conference, Chief Human Resources Officer conference. And the -- one of the guys from a Fortune 50 retailer that you would know stood up on the stage and said I'm not responsible for anyone's development other than my own. And I thought, oh, wow, that's like I guess HR is kind of advocating that they are doing anything to develop people's careers now. It really is all on us. Doesn't mean that they don't have things out there for people to use, but having a magician behind the curtain who's directing your career just doesn't happen anymore. It's just not happening anywhere. And people have different times and needs for what they do. So you need lots of options. Perhaps you've got young children and you can't be full-out committed to growing in a career at a certain point in time but at other points you can. And just like the 106-year-old I interviewed, everybody's got dreams about what they can do next. So almost everybody who's working professionally hopes to get into some other role. So we came up with five practices. And you'll see that there's a chapter dedicated to each of these in the book. The first one is learn on the fly. I'm going to go into each of these and give you a tip from each of them out of our like 30 different tips. Be open, build a diverse network, be greedy about experiences, and I'll talk about why greedy, and bounce forward. Not just bounce back, but bounce forward. Probably everybody in here thinks they're a good breather. Yeah? Most of you feel like you can breathe pretty well? Great. That's good to hear from an audience. And all you have to do is go to a yoga class and find out that probably you know nothing about breathing. Does anybody know the box technique for breathing? No. So there are different methods of breathing, you can breathe to reduce stress or anxiety. You can breathe to relax. You can breathe to deal with pain. There are all kinds of ways to breathe. Along the way, I was a chief talent officer for a Fortune 50 company, and I swear every résumé that came in said I'm a good learner. I'm a quick learner. So how do you know? I mean, it's the natural human condition to breathe. It's also the natural human condition to learn. So how do you know you're a good learner? Well, it turns out we don't actually know. We just -- because it's our natural human condition to learn. are there ways that we can learn better on the job. So Some people estimate that 70 percent of learning happens on the job. 20 percent of learning happens because a mentor or a coach, a supervisor really helps guide you. And another 10 percent, from sitting in kind of more formal learning situations, like today. So how can you get better at that 70 percent? When we think about stretching, it's so much easier to stretch when you're in the context of your own job and your day to day. So here's a technique. Here's just one of many from the book. This one I would like to thank some compatriots at Harvard Education, their Learning Innovation lab. And this technique, if you think of it, this is a really great time to think about this, because if you think about let's say the five to seven major goals you have for the year, for 20 -- does your fiscal year run the calendar year? Oh, no, so you're not in your goal-setting period. Well, the next time you're in your goal-setting period, think about the five to seven things that you have on your plate. And there are kind of three ways to approach those, a perspective to take when you're looking at your job. The first perspective might be you know what? I just need to get everything done. I've got a big to-do list, and I'm going to get it done. I'm a very efficient and productive person. So you might be one of those people that's kind of your go-to person for the boss because you just get a lot of work done. So the good news about that, the positive, is that you're well liked for getting a lot of stuff done and just getting things out the door. The bad news is, as a side effect, you don't really get to learn very much. And the reason you don't get to learn very much is because you're so focused on just getting things done. So you don't have any accidental learning that happens when you're really in super productive mode. The second perspective is called a performance stance. And in a performance stance, you think, okay, my boss really expects me to do this well, so if I do this really well, it's just going to be good for everyone around. Somebody's counting on it, it's going to be visible to a customer, whatever it might be. When you just take that mental stance of thinking about doing something well, accidentally you learn. So you learn because you've started to make a comparison between what does good look like and what does not good look like. And so you might talk to someone. You compare yourself to other projects that have been done before of a similar nature. And if you move to a development stance, then that's the one where you're thinking, you know, this might really leverage moving into the different role or helping me along the path I want to get to. One study found that software engineers who consulted with an expert for 15 minutes improved their productivity by 20 percent. So when you go to I really want to do this well and I want to learn from it and you go talk to people or you go do other things, you are learning. You're stepping forward a little bit. So here's the tip. You probably in your natural state of work gravitate towards one of these stances. For all your work. So instead think about sorting your work into different approaches. Do some where you just get it done so that you make room for some things to be done in a development stance. And some people really like to be super productive. Some people want to do everything well and then they don't get -- they don't have enough room, then, in their schedule to do a development approach. So there's tip number one. Take a stance on how you do your work. For those of you here in the room, and I think online they can see this, here's -- if I could recommend any book other than my own to read this week, or next, it would be Mindset by Carol Dweck. A very simple, straightforward book. I see you might have read it because you're nodding your head yes. So did you find it a really helpful book as well? >>: Very helpful. >> Karie Willyerd: >>: [inaudible]. >> Karie Willyerd: >>: Yeah. And it's become the hot new thing at Microsoft. >> Karie Willyerd: >>: Yeah. Oh, has it? Yeah. >> Karie Willyerd: Oh, okay. So other people know about Mindset as well. So she didn't write this exercise, one of -she's been writing about essentially you can take two approaches to thinking about work. You can take a fixed approach to growth or a growth mindset. And, in fact, when you think about this question, are leaders born or made, your answer to that inside your head will probably tell you whether you generally are a fixed mindset or of a growth mindset. And so here's just some questions. Are you willing to select a challenging work -- so these are from one of her co-collaborators. It's not in her book. But she helped work on it. So here's just a few questions. Do you look for opportunities to develop new skills? Do you enjoy challenging and difficult assignments? Are you willing to take -- to not look good at work or not look really extraordinary in order to take a few risks to learn something new? And that's kind of I think an interesting question to think about. And do you like to be around people with a lot of ability and talent? I think one of the -- I've changed over my career in terms of thinking about talent, because now I believe that we have high-potential programs in many companies, and after a while you'll see, you know what, the high-potential person went nowhere and somebody who no one thought just really came up out of blue and extraordinarily went past them. And I think that's sometimes about having a growth mindset; that if you just keep on growing -- committed to growing and learning every day, and instead of saying not now but I will be able to someday, you just can't estimate what the power for human potential is. So the second practice is to be open, to recognizing opportunities as they come along and not miss them by -- does anybody know -- don't say it out loud and don't look it up. Does anybody know who Ron Wayne is? No one. So this is an amazing thing. I've probably spoken to, I don't know, thousands and thousands of people about this story and no one has ever known who he is. So he was working for a gaming company, and a couple of his buddies, one who worked for the gaming company and one who worked at HP, decided they wanted to start up a company. So on the side. So they went off to the side to start up this little company. And he's the person who developed the logo, developed the first tech manual. Was really a significant partner. He owned 10 percent of the company, and the other two guys owned the other 90 percent. And there came a point not too far down the road where he decided it was time for him to go off. They decided it was time to go full time. Ron decided not to because he said you know what, my boss really needs me for this project. And so he made up his mind and he stayed in that place. So they bought him out for $1,500. And about a year later they got some venture capital money, and so they asked him to come back in. And he said no, my boss has another assignment that he really wants me to work on and I just don't -- I don't really want to do it. So he just really committed in his head. You can read his blog on Facebook about this where you can kind of see his thinking; that once he decided, he had just decided. Well, his partners were Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs and he owns 10 percent of Apple Computer. He's a founding partner of Apple Computer. Nobody has ever heard of him. Now, not all of us are going to bypass an Apple Computer opportunity in our lives, but who knows what we might be passing up. Because once we've decided and made up our minds about something, we haven't gone -- and some people really believe -in fact, talking to the researchers at Harvard about this book and everything, they said perhaps the most important thing that we can do is become open. Can we begin to think like novices think in terms of looking at experiences because there's a downside to being expert. I'll talk later about how important it is to become an expert. But the downside of being an expert is that you develop rules of thumb about how the world works. And your rules of thumb get more refined, they help you make decisions quicker. They make you an expert, but they can also blind side you when new rules come along. And so this being open is just a really interesting thing to cultivate. This is a friend of mine. His name is Chris James. He was in -- he'd been turned down four times for a promotion to vice president. He'd been a senior director for six years. So he said at that point he felt like, well, maybe I'm just not cut out to be a vice president. Now, what kind of mindset does that sound like? A fixed mindset. Right? I'm just not cut out for it. So he got another boss, a new vice president, that he had to, he said in his words, train yet another VP on how to do essentially his work. And the VP made an -- he could tell that he was frustrated. So they made a pact. She told him I will give you a lot of feedback about why I think you're not making it to VP, and in exchange I'd like you to run this part of the business and just do an extraordinary job on it. So they made that pact. And he said later I got more feedback in that six months than I'd gotten in my entire life. And it was little things. You can't tell from this picture, but he looks -- but he looks a little bit like the butler on Downton Abbey, and I guess maybe it comes across that way because he is Welsh. So he's got that really dry kind of like proper sense, but then in the -- you know, it turns out that he's got a wicked sense of humor. He just didn't let people see that very often. At any rate, he's one of these people, and you've all met these, that when somebody gives a presentation on a new idea, the first thing he does is come up with why is it going to work, why won't it work, what's the downsides to every idea. So that's all people could hear. And so they saw him as resistant to change. And he saw it as -- he says I'm like the most changeable person in the world. Look at how many countries I've lived in and so on. So it was a complete blind side for him. So he fixed it. He fixed it, and a year later he got promoted to VP. A year and a half later he got promoted to senior vice president. Two years later he became a chief operating officer for another software company. And he's today the CEO of a software company. After being stuck six years as a senior director. So I think everybody can change and we shouldn't accept that we are stuck. Perhaps there's a lot of feedback sitting out there for us already. What do you think -- how much feedback of the part that you get do you think you actually apply? Percentage-wise. >>: 8 percent. >> Karie Willyerd: 8? 7, 8. Yeah. Well, experts say about 30 percent. We're probably leveraging about 30 percent of the feedback that we need. And the higher you go in an organization, the less feedback you're going to get. Real feedback. I mean, you might get great feedback, but it's all going to be kiss your whatever feedback. You know what I mean? So what can we do to get the feedback we need? I had somebody that I was working with once who I thought did something really great. He was new. He was actually head of the supply chain for this company. And he went out and he did what I call now a perfect person comparison. After he'd been on the job about six months, he went out to people and he said you know what, nobody's perfect at doing a job, but if the perfect person were in my job and they were doing this job in the perfect way, what do you think they'd be doing differently than I am? And that's a really -- it turns out that's a really interesting question. Because it, A, creates a lot of safety for the other person to answer because they're not having to say you know what you should be doing this, they're saying, well, a perfect person would do this. It just takes a little bit of the personal out of it to set up. And if you watch your body language and if you ask for more clarification, you can get some really interesting and good feedback. So a perfect person comparison is another tip for how to get the feedback you need. That was a free giveaway tip. So here's my second tip. I've already put it on the slide. But there is no relationship between confidence and competence. And a lot of people, especially in the U.S., think there is. I can really go do this job. And we just like those kind of candidates who come in full of confidence and full of -- or I can do this project. So I've learned over the years to completely discount confidence. The only relationship that's ever been examined and proven in a relationship between confidence and competence is a negative association. More confident you are, the more incompetent you are. It's called the Dunning-Kruger effect. And, you know, especially newcomers who might feel really good or confident about a job, somebody new into a job feels like, wow, I really deserve this, I'm qualified for this, overestimates their capability. Or your boss might do it on your behalf -- boy, you can get all of this done. And they don't realize that the schedule isn't going to be made or within the budget or whatever it might be. So here's kind of a tip. And this one is also for women and for people who have disadvantaged backgrounds as well. In one study, a company, major company looked at -- it's HP, so it's public, so there's no reason not to say it -- looked at why weren't they getting more applicants into senior-level jobs. And what they found was when they went and asked men what percent of the qualifications for the job do you think you have to have in order to apply, what do you think men said? Somebody has read my book already. 60 percent is the right-on percent. About 60 percent. Have about 60 percent of it. So men felt confidence enough, if I've got about 60 percent of it, I'll go ahead and do it. What did they find women said they needed to have in order to qualify for ->>: A hundred. >> Karie Willyerd: 100 percent. So most women were saying I have to have everything on that job criteria in order to stretch. So if you're one of those people that worries about, one follow-up study said, well, a lot of times it's worried because they don't want to waste the interviewer's time or whatever. Actually, that's what their job is. So you shouldn't worry about that stretch. Go ahead and stretch and see what you can get to and do it scared. I had a friend who said her boss gave her a job that she didn't feel like she could complete. So she went back to her boss and said I just think this is a little bit over my head, and her boss said I don't care, do it scared. So there's a point in which we should all be approaching work from being just a little bit scared. That's how you know you're growing, is you're just a little bit frightened about what you're doing. In our research, the number one answer people gave us when we asked them how do you stay current, there's -- I don't know if anybody has as -- I wouldn't be surprised if my book goes to a nice little bedside stand of about 40 other books that you feel like you really need to read. Right? That you need to read in order to stay current and you just -- you feel a little bit of guilt. Or if I haven't induced guilt in you yet, I hope I do, for not reading the book. So the number one thing that people said was not that I read books, although that was -- reading was on the list, the number one thing was I hang around smart people. So I rely on other people who are smart and staying current to help me stay smart and current. So in a sense, building a guild. So what is the optimal way to build your network? We've all heard of social networks. We all have. Lots of people we might follow. So we're not talking about what's your Facebook feed look like and who's -- are you following George Takei in your network. No, we're talking about what's the best network to leverage your career. So let's think about this. If you had to get a new job, either inside or outside Microsoft, or you needed to get access to some really interesting information, which of these following two networks do you think would serve you best? One is a strong-tie network, and that's the people that are closest to you, that got your back. If you pick up the phone and ask them to do something, you know they'll do it because you've got enough of a connection to them. The second network -- and that might be your friends, family, and your colleagues. It's not a great big list. The second network is more diverse. Maybe you only keep in touch with them once a year, if that. They're a little more spread out. Probably you keep in touch with them about once a year. Maybe from places you used to work. It might be from your college days. Whatever it might be. So if you needed to get a job tomorrow and you could only pick one network, because of course you're going to use both, but if you could only pick one, which one do you think is going to be the most effective network for you? How many say your close, strong ties? Strong ties. And how many say weak ties? Okay. Well, this is the exact opposite of what almost every audience ever says because the answer is weak ties. So it is weak ties because they're more diverse. So your strong ties tend to know each other and tend to know of the same opportunities and know the same body of knowledge and know the same connections. They're only like a degree away. But your diverse network, your weak ties, are more spread out and just have more opportunities that they're aware of than you know of. So it's important to develop not only strong relationships but also weak. So I'm going to talk about strategies for each of these, your weak ties and your strong ties. There's a researcher named Robin Dunbar, and he's looked at how effective of a network can we groom. And he started by looking at chimps and found that they could manage about a tribe of 50 because they had to groom them and, you know, if it got bigger than 50, the animals would start to get stressed out because they couldn't groom more than like 50 within a tribe. Well, humans, it turns out, it's about 150. And so there's about 150 people that we can groom. So the first thing I think to do is kind of look at your LinkedIn or look at your other ways that you have networks developed and are there 150 people that you can -- in the old days we would send a holiday card to. So are there 150 people that you can keep in touch with one time a year? And that is the key. So Dunbar says if we let a relationship go more than one year, it degrades. But you can kind of keep it in touch if you keep in touch with 150 people from a diverse -- and it just means a quick e-mail, hey, was thinking about you the other day, how are you doing. I mean, cut and paste it and put it into 150 separate e-mails. [laughter] >> Karie Willyerd: But, you know, just keep in touch. Because you know what it's like when somebody contacts you after three or four years and says, hey, I'm looking for a job, and you haven't heard anything from them and all they want from you is that. But if you've been in touch in the meantime and you say, hey, I think I'm going to make a change, I'm thinking about looking around, what do you -- have -- and you've been in touch with them, it's a whole different ball game. And it's particularly a whole different ball game in you've done them a favor during that time. So I have a rule of thumb that I return every headhunter's phone call just to tell them not interested but I might know someone who is, and then I try and keep other people connected. And it's really stuff I do at seven or eight o'clock at night. It's not, you know -- I don't have time for it, but it -- but headhunters are a really good hub of many social networks. And it's not only them that I'm keeping in touch with. There are so many people that I've done favors for along the way like that. Because I've been in HR, I've advised a whole bunch of people on how to negotiate a new salary. There's a lot of tricks on how to get more out of it. And, you know, you just have to help people earn more money, and they're your friends forever. So then you just have to kind of keep in touch with them. So, you know, little tricks like that. One more trick for creating a close-tie network is think about the people that you're spending the most time with. Some management consultants like to say, oh, you're the average of the five people you spend the most time with. And then I thought, oh, that's kind of tough if you got four kids. [laughter] >> Karie Willyerd: So instead think about who are the people that every time you're with them you get a new idea or you think, wow, that person is really well read and they are -they're just kind of like pulling me into some new stuff that I don't think about. Or they inspire you or they motivate you. And ask yourself are you spending time with those people. And when I kind of went through that thought process, I realized I wasn't. I wasn't spending enough time with those people. So our suggestion is find those five to thrive and spend at least once a quarter with them. So if you just kind of think right off the top of your head, because a lot of times we spend our lunches with people that are convenient that we work with and maybe you're the person who's the strength giver in that group. And that's what I found is a lot of people were seeking me out to mentor them, and I was spending a lot of time with people like that but I wasn't getting enough from spending time with people who inspired me and who gave me new ideas, and I had to go out of my way to make those meetings happen and build them into my schedule because they were just as busy as I am. How many people think, as you just kind of tick them off right now, that you've got those five people? A few. So for those on the phone, maybe 20 or 30 percent in the room thought they've got those five people now. And then ask yourself are they diverse enough. So when I really thought about it and did, okay, here's the five I want to do, I said, oh, gosh, they're all women. And, you know, it might be for some men that it's all men. Or, you know, it's all people that are in my same workgroup. Or whatever it might be. So think through, you know, who are your five to thrive, and then strive to make that a diverse group as well. Because that's how your thinking gets stretched. It might be someone that you're not totally socially attracted to but their brains just really spark something in you. So if you can kind of overlook some social discomfort, can you find a diverse group of five who really inspire you. So why is it okay to be greedy about experiences? I talked to a young woman who's going back for an MBA, and she said -- I teach in a couple of colleges as a guest lecturer, and she was talking to me, and she said, you know, I sort -- I said, so tell me your experience that led you back to being an MBA. And she said, well, I'm an engineer. And she worked for a big aerospace company. I said, so tell me some of the experiences you've gotten and so on. And the more she talked, the more I realized, you know, she really has one year of experience that's been repeated five times. So on her résumé it's going to show five years of experience, but it wasn't five years of growth. It was the same experience over and over and over. So you might have a manager that tends to, well, this person does this really great, and so he or she gives them all those kinds of assignments and this person gets all kinds of assignments this way or that way. And it's really got to be on you. Going back to the first imperative, it's all on you. It really is on you to get the experiences you need. Don't just put your life in the hands of whatever supervisor you happen to have at the moment. And so here's some tips for doing that. First off, before when we said do it scared, one of the things that we say is, you know, just ask yourself the question, when was the last time I felt in over my head? And for some of you -- don't raise your hands, but for some of you, it might be a year or more. Or some of you it might be in the last six months. Our advice is at least once a quarter be able to say, gosh, I felt in over my head. That will be kind of a little bit of a clue that you're getting new experiences. Because if you're getting new experiences, you're going to feel like, you know, you're just going to grit your teeth a little bit and wonder if you can really get it done. And there's lots of different ways to gain experiences. One of the things that we said was set a learning experience goal earlier when we said, you know, just pick one of your projects. And, you know, one of the -- so I think I've got a slide in here on this one. I'll just skip to that slide. And read, travel, study, interview. Here it is. Sometimes we think of a boss, a good boss, as someone where we go to work and life is easy. They're really fun. We do stuff after work together. They make it manageable for me to do work-life balance. And so we think of that as a good boss perhaps. But a few years down the road you might realize, you know, I haven't really grown. I haven't really stretched in the time I've been with that boss. Another boss might be a perfectionist. Because I worked in the Silicon Valley, I interviewed a bunch of people that had worked directly for Steve Jobs. And he said he wasn't a comfortable boss to work for. He wasn't an easy boss to work for. But I did my -- almost to a person, they said I did my best work working for him. So sometimes what we think of as a good boss or a bad boss we might need to reframe in terms of are they helping us with our career. I interviewed a woman who was in China, and she had -- a millennial, and she'd been in the job three years, which in China, in that part of China, was like unheard of. You just didn't stay that long in a job. And I asked her why she had. And she said, because every time my boss hands me an assignment, he tells me what I'm going to learn from it. And she said I don't think I'll ever get that again in my career. I don't think I'll ever get it again. So here's the tip for you. Perhaps your boss doesn't think about these things. So ask your boss, what do you hope I'll learn from this. And if you are a boss, when you're handing out assignments, help get that. I know two people who approached their boss and said can we just flip jobs in order for each of them to be able to learn and not affect the boss's overall work. And the last thing is to figure out strategies for motivating yourself when you have a setback. Here's just one person's setback. He failed his college entrance exam three times. Couldn't get into the police academy. This was the biggest insult. Kentucky Fried Chicken opened up a store in his area, and out of the 24 applicants, he was the only one that wasn't hired. So he decided he had to start a new company. And who he is Jack Ma, one of richest men in China. If you haven't ever heard of his story. So one strategy, one mental strategy to use is that bad is stronger than good. So by that I mean when you have a setback, when you have a failure, a disappointment, you are always going to remember it. So what a great learning strategy. So instead of sitting and dwelling on what happened that was awful, what should I have done differently, it is good to reflect on what could I have done differently, because that is learning. But don't get stuck there. Realize that that's an opportunity not to just get back to where you were but to move forward because you've had that great learning opportunity. And so with that, I'm just going to go to -- I'm going to go to -- we spent a summer with some interns looking at every study we could find on projecting the capabilities needed for the future, including some Microsoft studies. And one thing that we found, there's some really good ones in here. One I don't have up here at the moment is we called geek acumen, which is every job needs to be technical now. It is no longer going to be acceptable to say I'm not really technical. You just can't say that. I don't care what job you're in. I actually mean that for every job. You must be a little bit technical. That's how you're going to keep up with the robots that want your job, is, you know, to just be a little bit technical, be able to work alongside them. But there is another Powerball combination of skills that we found in doing this kind of meta analysis across studies, and that is get deeply functional expert, become a deep functional expert in one area. Whether you're an engineer or you're in HR or you're in finance or you're a software engineer, learn not only your domains but the sub domains. So if you're in marketing, get not just one sub domain like social marketing, but get other sub domains and become expert. Be kind of the go-to person in expertise. And the second Powerball combination to that is emotional intelligence. And the reason is is because it helps you get a job, it helps you collaborate. That's going to be one of the biggest skills that companies are looking for going forward. It helps you navigate the politics of an organization. And if you think you're the only organization that has politics in it -and I'm assuming all of you feel that way -- think again because they're everywhere. And it helps you get your next job. deep functional expertise. So So with that, I think I'll just jump to the final slide on where can you find more information. I hope you had a chance to look at the book. And if I could open it up for questions, I think there might have been some in the room. Or if any came in online, we've got time for questions. You can -- the easiest way to remember to get me is on Twitter, @angler, because I fly fish. And you can tell I got on Twitter early to get that handle. I've been offered a lot of money for it by fishing companies. Any questions in the room or comments or thoughts? Yes. >>: A question online. The global survey at the very beginning of the talk, they wanted to know if there was a breakdown by age as well. >> Karie Willyerd: Yes. We did break down by age. And when we were -- in fact, we -- that was one of the big drivers of the study, was we wanted to like spread so that we got all ages. And we find there's not as much difference between preferences for what people want to do at work as we assume there are. Because when people say, oh, well, millennials love technology, well, we all love technology. So the differences were not significant by age. The one -there were a few places that were significant. Millennials want more development. That makes sense. They're earlier in their career and they'd like more development. They also want more feedback. And I think we're the first people to have studied that. So very specifically baby boomers were comfortable with feedback from their boss a couple times a year. Gen X wanted it maybe three or four times a year. And millennials on average want it every month, a formal, sit-down conversation with their boss once a month. So that was the one big difference was the amount of feedback I get. Which is why we think it's really important to not only be able to receive feedback but give feedback. And so we talk about how to give feedback in the book as well. Yes. >>: Has fly fishing provided you any further insight on your research [inaudible]? >> Karie Willyerd: Fly fishing has not, I don't think, directly provided me insight. Although, learn on the fly, we're both fly -- we both fly fish, and so we spend some vacations fly fishing. So learn on the fly was deliberately from our fly fishing experience. If you haven't ever fly fished, though, it is a way to just completely decompress because if you want to stay alive in a river that's moving quickly and you actually want to catch fish at the same time, you aren't thinking about work. So it's a way to go from 100 miles an hour to just totally in the moment. So do you fly fish? Anyone else? Yes. >>: I haven't read your book yet, but do you have any -- >> Karie Willyerd: It's only two weeks old. >>: Okay. Do you have any tips or maybe guidelines about how you select from options you have that provide learning? >> Karie Willyerd: Yeah. So I would say because so many people told us, so many really great people, like we interviewed a sub domain of people who had all won awards in their community from across the country, just the U.S., but we asked questions around the world, and the number one answer was hanging around smart people. And so if I think if you were only going to pick one tip, it would be just really develop that small community of your five to thrive. Pick people that may not be in your closest network now but you groom to get there. So offer to take them out to coffee. Make sure they're getting something from it too. And so that would be my number one tip, is groom your five to thrive. It's also kind of the easiest. Or one of the easiest things to do. You know, read this book. things. Yes. Read Mindset. That'd be my top three >>: So how do you know when to move on? When do you feel like you've learned enough? Because you could stay in one place and technically create things to learn indefinitely, but how do you know when it's just time to move on to a new set of experiences and kind of cut that cord? >> Karie Willyerd: Yeah. Yeah. So I think the outside edge, as we said earlier, was once a quarter you feel in over your head. So I think it's kind of like popcorn. In popcorn you kind of know to stop it before it gets to the -- if you let it wait until there's like pop, pop, you know, then it's too late. It's already burned. So I think it's kind of the same thing with being in one place. If you're kind of having to make it work to get another pop out of it, then I think it's time to move on. And it doesn't mean that you can't move on inside working for the same manager. Again, flop jobs. Or because I worked with a couple of accelerators, it's amazing how many people will come volunteer their time on weekends and nights to work with local accelerators and just get some experience in and rejuvenate that way. We had one software developer who came to work for us who took a six-month part-time sabbatical and just really got to experience the whole software development cycle because he worked for a great big company and he had always been in like one thing. So he didn't know how to do agile programming and how to know -you know, he hadn't even qualified to be a scrum master yet. But inside this company he got to do that plus paired programming and all kinds of things that he was then -- the company didn't work out, that second company, but he went back to work and just got two really quick promotions because he got that rejuvenation while staying in job, essentially. Yes. Back here. >>: I have a question regarding the five to thrive. If somebody you've identified is really senior, like super, super senior, and you're asking for their time sort of on a quarterly basis, what is it do you think that somebody could offer them or give them or bring that is somewhat of value to them when you are like so much, you know ->> Karie Willyerd: >>: More junior, yes. Yes. >> Karie Willyerd: So I want to make -- I do want to make a distinction between perhaps having a board of directors, a personal board of directors, and your five to thrive. A personal board of directors might be people you seek advice from once a year or once every 18 months to just say am I on track kind of thing and looking at them. So if it's a really senior person, you know, I think there's two things you can do. I work -- I'm on adjunct faculty at Crotonville for GE, and we've set up reverse mentoring programs there. And to a person, the people who are being mentored who are the senior executives feel like they get something out of it because that more junior person has brought them a perspective about how are people making decisions that are at that level or helping them stay informed. So I think if you're going to reach out to someone like that, couple of things. You make it worth their while because you're listening to what they have to say and they can see that you are and that you're doing something with it. Because that like used to drive me crazy at Sun when somebody would ask me to be their mentor and then they wouldn't do the work in between the sessions. I would drop them like a lead balloon. And then, secondly, bring something to the table for them. So think about them and what you can bring to the table from your experience. Because your experience is different than theirs. Like I said, the higher you go, the less feedback you're going to get. So how can you say here's what I see going on in the organization. I don't know if you're seeing the same thing. But like at my level and in my group, this is what I'm kind of seeing. How do you think I should be interpreting that. Or how should I be helping in that situation. But you're giving them some information that they don't perhaps get to hear because of where they are. Yes. >>: When you think about looking for different development experiences, do you recommend going for ones that build on your strengths or mitigate weaknesses or balance between those two? >> Karie Willyerd: Yes. So I think it depends on the risk associated with it. So, in other words, if you can stretch into a new area where you don't really have any skills at all, and it won't be risky, then give it a whirl. But if it's going to be risky to your career, then I think you need to take incremental steps to get to it so that -- because people have long memories. And so you need this opportunity to keep your career solid if you plan on staying in the same company and not jumping. Microsoft's big enough that you could jump from one area to another and people might forget, but -- but I'd say stay safe as well. Yes. Mm-hmm. Practice safe stretch. [laughter] >>: So one point you were saying deep experience, right? So do you think there's anytime in your career that you need to get breadth, though, and not ->> Karie Willyerd: Breadth of experience? Yes. I've done work for an intelligence organization with three letters, and one of the reasons they believe that 9/11 happened is because they had so many people -- about 80 percent of the people they had were in deep analyst positions. And things didn't cross the silo. So there were lots of things sitting in lots of places but not people who could see across. And so we really recommend what's been called by others a T-shaped career. So you get deep functional expertise and get some experience that takes you across as well. And it's just a matter of what your career ambitions are. So if you really love your field and you're passionate about that, then make it kind of an 80/20. But if you have a desire to move up in the organization into more general management kind of thing, then flip that and go 80/20. But make sure you've got some deep functional expertise in something. So people look at you and they can -- and they look at you for being an expert in what you know. So I think we're going to want more and more people who are able to go sideways. Yes. Do we have an online question? >>: Online question. When I apply to a new position in a different business or product group, how do I persuade the hiring manager if I lack a desired experience and I'm super interested in that product? Or in that position. Excuse me. >> Karie Willyerd: Yeah. So I would say look for ways to gain some experience that you can position and sell as being relevant. So if you think it's going to be very difficult to go in and sell them on it, from what they have, then figure out a sideways angle on how to get that experience. So I suggested go to your local accelerators or startups and ask them can you volunteer your time. Can you ask, hey, I'd like to come in and do a special project for you. I had another person in my first company who said -- he had a liberal arts background. He wanted to move to Germany and go to school there, but he thought the only job he could get that would sustain him while he was there was to be able to do programming because he could do that globally. He had no programming experience. And so he said, can I come to work for you. And I said sure. You know, no money. But what we will do is let you sit alongside other developers as they're working. And as soon as you show you can add value, we'll pay you. So it took him seven months. But now he is working in Germany as a Ruby on Rails developer full time. So I wonder if there aren't ways in which you can go in and just volunteer: Hey, can I just come in and offer my spare time on a project that you've got going to show you that I'm really interested in that and that I can get experience in this. And I hope that leverages my way to a job someday, but in the meantime it's something I really want to learn. You know, I'm going to go with the rule of 90 percent of bosses are going to be okay with that if they can figure out that you're giving to them and you really are doing it on your spare time. So it's a matter how much do you want it. Yes. >>: So you mentioned that a big part of the challenge you see in maybe 10, 20 years is going to be how a lot of our jobs will be computerized. >> Karie Willyerd: >>: A lot of what? Our jobs will be computerized. >> Karie Willyerd: Computerized, yeah. >>: And so -- and our populations continue to grow. And so how do you think, as we think of -- we often think of STEM, so science, technology, and math. When we think of our children and who we're interacting with, what should we be teaching them so that in a generation, you know, they're prepared for this? >> Karie Willyerd: Right. >>: Because we -- most of us will be close to, you know, retirement ->> Karie Willyerd: Yeah. There are a number of really future-looking people who are talking about this, including Bill Gates and Elon Musk. They both have talked about are we preparing at a societal and policy level for handling that. So I had my children when I was four, so I have grandchildren, and so I have a 12 -- well, he'll be 12 in a couple of weeks -a 12-year-old and a six-year-old girl, and I pay for summer tech camp for each of them. So they are both, you know -- already the six-year-old is programming in Java. And she's probably not going to be interested in a Java career. I don't think she should be interested in a Java career. But she's definitely going to be technically prepared to -- you know, even if she wants to pursue fashion, technology and fashion are so integrating now that I just think it's really important for us to prepare our children and make it fun. I mean, they've got a lot of technology camps now. The one I use is called iD Tech Camp, and it's held at almost every college in the country over the summer. So that's where -- I sold a software company, so I can afford to send my kids to -my grandkids to stuff like that. But if not, there's a lot of online free learning as well. And there are some great -- oh, does anybody remember the name of that program that you learn that's just kind of meant for kids, that's just ->>: Scratch? >> Karie Willyerd: everyone? >>: Yes. Yes. Can you say that louder for MIT Scratch. >> Karie Willyerd: Yeah. Yeah. So I think there's a lot -- so I think -- and teaching them not to be afraid of technology. So, you know, I give my grandchildren leftover laptops, old laptops, and we take them apart as a -- just a Saturday game event. We take apart other, you know, just appliances and things and just let them kind of experience what -- that things are things and that they run for a reason. And give them that experience of it's like okay not to be afraid of and let them mess with the TV and get the menus all wrong and have to reprogram it all yourself, but let them go into the submenus and so on to just kind of figure out that all of this actually is logical and makes a lot of sense. So take away the fear by familiarity. Yes. >>: Can I comment on this? >> Karie Willyerd: Uh-huh. >>: So a few months ago we had a speaker, was talking about the [inaudible] automation. >> Karie Willyerd: >>: The what people? The interaction of the people and automation. >> Karie Willyerd: Yeah, people and automation. Yeah. >>: Right? And [inaudible] robotic [inaudible] and starts working well when [inaudible] partnership. >> Karie Willyerd: >>: Right. [inaudible]? >> Karie Willyerd: That's what I think too. I agree with that, that we are going to be -- but there are some people that aren't going to want to make that transition. And for some people they'll wait too long and the transition will be so difficult it will be overwhelming. Which is why I say stretch a little bit every day to be ready. Because if you are stretching every day, it's just going to be a continuum. It's just, you know, a little bit more here, a little bit more there every day. No. Don't wait. I've had some people come up to me. My last book was called The 2020 Workplace, and I had -- I was telling the book sellers and so on here that people would come up to me and say thank God I'm only -- I'm going to retire in less than five years because I don't want to have to change. And I said, if you're not going to change for five years, you're not going to make five years. Because the world is changing that fast. You just cannot sit still now. I think we have one of the biggest revolutions going on underneath our feet right now that mankind has ever seen. And it just takes us being a little bit ready every day, and we'll make it. >> Debra Carnegie: Thanks so much to Karie. >> Karie Willyerd: Thank you. [applause]