Local Policies for High-Employment Growth Enterprises Niels Bosma

advertisement

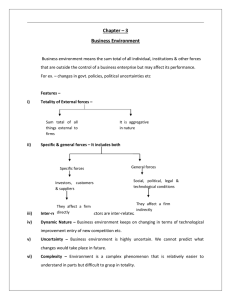

Local Policies for High-Employment Growth Enterprises Niels Bosma Erik Stam Utrecht University School of Economics Perspectives on High-Growth Enterprises Issue External Resource providers Public Policy advisers Firm owners Roles for management in rapid growth Management is key but need to be receptive to outside help Management is key but outside advice can help Management’s vision and experience are key Roles of external resource providers External resource providers are key External resource providers can be beneficial but peer mentors can substitute External resource providers are sometimes necessary, but expensive Roles of Government in supporting rapid growth Governments have no direct role to play Governments have multiple, critical roles to play Governments can be helpful but public support is not necessary and cannot be relied on Is rapid growth good? Rapid-growth is good for (our) business Rapid-growth firms are good for the economy and politically beneficial Controlled growth is preferable Source: Fischer and Reuber (2003), with minor adaptations Perspectives on High-Growth Enterprises Issue External Resource providers Public Policy advisers Firm owners Roles for management in rapid growth Management is key but need to be receptive to outside help Management is key but outside advice can help Management’s vision and experience are key Roles of external resource providers External resource providers are key External resource providers can be beneficial but peer mentors can substitute External resource providers are sometimes necessary, but expensive Roles of Government in supporting rapid growth Governments have no direct role to play Governments have multiple, critical roles to play Governments can be helpful but public support is not necessary and cannot be relied on Is rapid growth good? Rapid-growth is good for (our) business Rapid-growth firms are good for the economy and politically beneficial Controlled growth is preferable Source: Fischer and Reuber (2003), with minor adaptations Perspectives on High-Growth Enterprises Issue External Resource providers Public Policy advisers Firm owners Roles for management in rapid growth Management is key but need to be receptive to outside help Management is key but outside advice can help Management’s vision and experience are key Roles of external resource providers External resource providers are key External resource providers can be beneficial but peer mentors can substitute External resource providers are sometimes necessary, but expensive Roles of Government in supporting rapid growth Governments have no direct role to play Governments have multiple, critical roles to play Governments can be helpful but public support is not necessary and cannot be relied on Is rapid growth good? Rapid-growth is good for (our) business Rapid-growth firms are good for the economy and politically beneficial Controlled growth is preferable Source: Fischer and Reuber (2003), with minor adaptations High-growth enterprise Ambitious entrepreneur Gazelle High-growth enterprise High-growth firm someone who engages in the entrepreneurial process with the aim to create as much value as possible (Stam et al. 2012: 26) >20% growth per year in 3 subsequent years, for firms with 10 employees or more; born 5 years or less before the end of the 3-year observation period (OECD 2008: 20) >20% growth per year in 3 subsequent years, for firms with 10 employees or more (OECD 2008: 10) Firm belonging to the group with the highest rate of growth of a population, in a particular period (e.g. Ten Percenters; see Parker et al. 2010) Local Policies Policies that are designed and delivered by subnational governments and (semi)public organizations, including actions by regional and local governments and by state governments in federal countries, as well as policies that are designed by national governments but that have intended or unintended spatially uneven effects. Relevance of High-growth Enterprises • Disproportionate share in total employment creation – NESTA (2009): 6 per cent of all UK firms with ten or more employees could be seen as high-growth firms adopting the OECD definition. These 6% were responsible for more than half of the new jobs generated by the UK firms employing ten or more employees. – The Canadian Growth Firms Project found that 2.7% of firms met the criteria for “leading growth firms” and accounted for 60% of job growth between 1997 and 2000 (Davis 2009). – Autio (2007) considers, rather than performance on hindsight, the expected contribution of entrepreneurs. He finds that the X percent of entrepreneurs that expect to create 20 or more jobs in the next five years, account for .... • Creation and diffusion of innovation • Create new markets • NOTE: What are the main characteristics of high-growth firms? Certainly not always in ‘high tech’ sectors… Multilevel Policies Policy effects Local Policy source Regional Local Municipal economic policies (e.g. incubators), land use regulations Regional Regional development US state level labour agencies, regional public regulations (e.g. nonventure capital compete agreements) National National science policies (affecting local university policies) SBIR, industrial policies (e.g. biotech), cluster policies Supranational European structural funds, European Investment Bank capital European structural funds (ERDF), European Investment Bank capital National National employment regulation Types of High-Growth Policies • Enabling policies for high growth enterprises – Gov’t interventions not targeted at certain (high growth) segments. It is basically assumed that new entrepreneurial activities resulting form these policies would also yield high growth enterprises (might sometimes be conflicting…) • Targeted policies for high growth enterprises – Ambitious entrepreneurs: target high potential individuals (see Stam et al. 2012) – Start-ups -> gazelles: business accelerator programs, based on selection of (high potential) start-ups; seed capital – Gazelles -> high-growth enterprises: peer learning, specialist services and networking for continued growth; venture capital Policy mix • • • • • Belgium Canada Netherlands Spain USA Accelerator Programs • Accelerator programs are ‘fashionable’; high (local) beliefs in the merits of such programs • Programs are backed by public or private organizations, often public-private support Accelerator Programs: Examples • • • • Belgium, Leuven: IMEC Canada, Toronto: MaRS Netherlands, Utrecht: UtrechtInc USA, New York: General Assembly Accelerator Programs: Success? • Proper Evaluations still lacking • No evidence of their effectiveness and additionality Conclusions: Main Findings • Governments increasingly support ‘enabling’ policies over the more traditional ‘targeted’ policies • Targets that are identified mostly have to do with the local industry structure – local strengths are being emphasized as potential breeding grounds for new, promising activities – ‘fashionable’ industries: clean tech, biotech / life sciences, ICT / new media • Local governments see a limited role for themselves when it comes to picking winners • Business accelerators programs pop-up increasingly, however with unknown success Conclusion: Propositions • Proposition 1: Local policies for high employment growth enterprises will be less successful in areas where regional, national and supra-national policies are potentially conflicting with the proposed local policies – E.g. local initiatives for fostering high growth entrepreneurship may be less effective in a national context of strong employment protection legislation, or with disproportionate regulatory burdens on firms beyond a certain firm size threshold • Proposition 2: Local policies should appreciate the local context in terms of and industry structure, resources, demography, culture • Proposition 3: Local policy makers need to be aware of the strengths of close neighbors. Competing with them may be far less rewarding than collaborating (for example through niches and stressing other regional amenities) Conclusions: Critical Notes • Local policies for high growth enterprises: Is high growth enterprises the appropriate target? – Enabling policies would not aim for high-growth per se (policies for an entrepreneurial economy) – Controlled growth sometimes preferred – Growth may take within businesses through ambitious entrepreneurial employees • Local policies for high growth enterprises: What is the scope for local policy? – Many relevant determinants originate at the national level (formal institutions, education, culture) – Local policy should appreciate strengths and limitations of neighboring regions Local Policies for High-Employment Growth Enterprises Niels Bosma Erik Stam Utrecht University School of Economics