September 30, 2005 Kimberley R. Isett, Ph.D. 600 West 168

advertisement

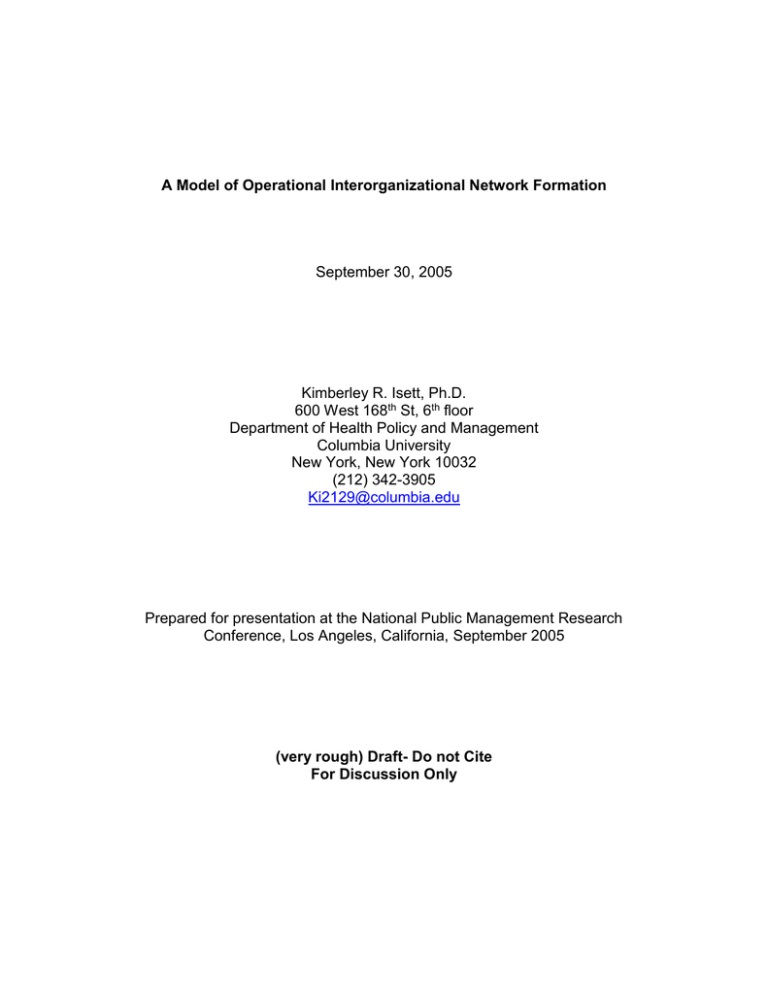

A Model of Operational Interorganizational Network Formation September 30, 2005 Kimberley R. Isett, Ph.D. 600 West 168th St, 6th floor Department of Health Policy and Management Columbia University New York, New York 10032 (212) 342-3905 Ki2129@columbia.edu Prepared for presentation at the National Public Management Research Conference, Los Angeles, California, September 2005 (very rough) Draft- Do not Cite For Discussion Only A Model of Interorganizational Network Formation Abstract Interorganizational relationships (IORs) in the production of public services are a fact of life. IORs stem from a number of factors that are well documented in the organizational theory and public administration literatures. These factors include, but are lot limited to: environmental turbulence, political advocacy, resource scarcity, joint production functions, broad organizational missions, power and relationship asymmetry, and institutional coercion (DiMaggio & Powell 1983; Galaskiewicz 1985; Oliver 1990; Milward & Provan 2000). However, in some cases interorganizational relationships are something more than just a series of relationships between two organizations. Instead, they become a network. Networks are created by dyadic relationships, without a doubt. But networks are a governance mechanism (formal and/or informal) among those organizations that belong to it. They have shared goals and processes that extend beyond two organizations, to a multitude of organizations that create a unified response to a given phenomenon (Chisholm 1999; Alter & Hage 1992). Interestingly, networks may be formed in several ways: from the bottom-up as a collective response by individual organizational actors; from the top- down through institutional mandate or coercion; and through some combination of the two approaches. While we know lots about interorganizational relationships, and a good deal about interorganizational networks, one critical element of networks has thus far been overlooked by network scholars is network formation. This paper seeks to address this gap in the literature by developing a model of interorganizational network formation. This model has been developed from the extant literature on interorganizational relationships and networks, drawing heavily from the organizational theory and management literature. While the organizational theory and management theory forms a base for the model constructed, insights from other disciplines are capitalized upon. Literature from political science is particularly emphasized, especially the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework (Ostrom 1990; Ostrom Gardner & Walker 1994). The combination of empirical and theoretical knowledge emanating from the three disciplines (public management, organization theory, and political science) creates an opportunity to develop a comprehensive model of interorganizational network formation without emphasizing either top-down or bottom-up approaches –a common shortcoming in the existing literature. 2 A Model of Interorganizational Network Formation Interorganizational networks have become a prominent method of organizing social interaction in the past two decades. As such, this phenomenon has gained increasing interest among organization scholars across disciplines. The existing literature on networks mainly focuses on how networks work, the structural aspects of networks, and the organizational and social outcomes of networks. However, scholars have yet to focus on the early stages of network formation. One potential reason for the scant attention to network formation is the close alignment of the interorganizational relationships literature to the interorganizational networks literature. Indeed, much of the research conducted on networks is a natural outgrowth of interest in and research on dyadic or organization set relationships. However, the phenomenon of interorganizational network formation is different than simple interorganizational relationships and deserves some concerted attention. The literature on Interorganizational relationships (IORs) has been well developed. This literature focuses on why two organizations would decide to form a relationship. Seminal works on explaining why IORs form have included both management (c.f. Oliver 1990) and sociological perspectives (c.f. Galaskiewicz 1985). These works focus on the linkages between two organizations or the linkages from one organization to another. While this perspective is a valuable starting point for a network perspective, it needs to be built upon to capture the differences of networks from dyadic relationships. 3 The primary difference between interorganizational relationships and interorganizational networks is the need for collective action. Networks require that many organizations come together to pursue a common goal in a coordinated and concerted way. This requires more than a simple calculus of benefit for joint production or exchange. It requires a trade-off of short term and individual pay-off, for longer-term collective benefits. Just how does an organization come to a decision to participate in a network? What are the factors that contribute to network formation? This paper presents a model of interorganizational network formation to begin to address these important questions. The model presented in this paper builds on ideas of collective action and synthesizes them with the existing IOR and networks literature to provide one conceptualization of interorganizational network formation. Through this model, I seek to elucidate the similarities and differences between interorganizational relationships and networks, as well as provide insight into the process of network formation. Conceptual Background Networks are self-governing institutional arrangements. These arrangements may be explicitly designed, as in many governmental service delivery systems (see Provan and Milward 1995 and Isett and Provan 2005), or may be more organically developed, as in many environmental management 4 focused networks (see Ostrom, Gardner, and Walker 1998). Regardless of the way in which they were developed, all networks have a common archetype. All networks are flat governance mechanisms in which actors come together to devise rules of interaction focused on joint goal attainment. The goal attainment may be productive, social, or conservation oriented, but requires collective action to achieve those goals. Thus, the actors in the network come together to share decision making efforts and authority in regard to the network goal (Alter and Hage 1993; Powell 1990; Scott 1981). One perhaps obvious statement about networks that is worthwhile to state is that network members come together to both give and take organizational resources to/from the network. Incentive to participate in networks comes mainly from an organization having the opportunity to achieve a goal that it otherwise would not be able to achieve on its own, similar to why organizations-proper form. However, an organization must give the other network members a reason for including them in the network as well as a reason for sharing their organizational resources through relationships. Thus, organizations must have something to give as well as to take away from networks. While this exchange may not be symmetrical, there is still some benefit to the exchange for the parties involved. Coordination of activities is an expensive and time consuming (Dill and Rochefort 1989). Thus, it is not worthwhile for organizations to participate in network activities if there is little to gain, or if the organization can achieve its purposes without the network. Although organizations will subsume network 5 goals and agendas to their individual goals and agendas, the network still aids the organization to accomplish something on its agenda. Thus, the benefit of network activities must come into balance with individual organizational activities and provide some real benefit (tangible or intangible) for the organization. Further, to reinforce the point above, if an organization offers no reason or benefits to other organization to interact with them in a network, then it is difficult to discern why an alter organization would spend the resources needed to coordinate and establish a relationship with the ego organization when their resource would be better used developing other relationships. Further, these exchanges in networks are not caused by serial interdependencies (Thompson 1967). Serial interdependencies can easily be solved through traditional market transactions. Instead, networks are more of a function of complex integrated interdependencies. Integrated interdependencies means that actors must put their resources into the production of an outcome at the same time and have those contributions interact with other organizations’ contributions; without this interaction and synchronous contributions the outcome or product of the network will not be achievable. While networks serve network members by guiding action and activities (Isett and Provan 2005), they also serve members in other ways. Network members capture benefits of remaining formally independent and small, such as speed of innovation, while reaping economies of scope and scale as well through the structure of other organizations (Powell, Koput, and Smith-Doerr 1996). Thus 6 networks offer its members flexibility in terms of the resources of time, transition, and cost (Sabel 1989). Despite this knowledge of how networks work and the benefits members receive by belonging to them, the knowledge on how and why networks form is still scant. The early literature on interorganizational relationships suggests that organizations form relationships in order to compensate for resource dependencies and uncertainty. More recent literature on interorganizational relationships has developed reasons such as legitimacy, information needs, and stability. James Thompson (1967) suggested that organizations will buffer their core technologies from environmental turbulence. This means building structures at the governance level of the organizations that focuses on boundary spanning and acquiring needed organizational resources from that environment. Buffering is particularly important in turbulent environments. Turbulent environments present uncertainty for organizations in that conditions (political, environmental, market, and/or social) are changing and organizations have to face contingencies about how and where they will capture organizational resources, a type of state uncertainty (Milliken1987). Turbulence in the environment leads organizations to seek interorganizational relationships in order to smooth out environmental perturbations and to have more certainty with regard to resource acquisition (Oliver 1990; Galaskiewicz 1985). More turbulence leads to greater need for interorganizational relationships, and perhaps more of them. 7 Not only do interorganizational relationships help organizations even out their resource acquisition, but it also helps them in their planning and strategic management. Organizations seek out stability from their environment and their operations. While this is a similar point to the idea of buffering core technologies and dealing with uncertainties, it merits further explication. Stability of relationships and within the environment helps organizations to better adjust to market conditions and to other contingencies it encounters. We see this concept most clearly from the contracting literature in both management and public administration. When organizations contract with other organizations, they must adjust their operations to accommodate the style and requests of their partners. This is especially poignant if the partner is a major source of the focal organization’s business or service recipients. Thus, if a contractor changes, the organization must go through a new adjustment period which may disrupt operations and takes time to learn and anticipate partner needs (Uzzi, 1997; Larson 1992). Therefore, contracting can become a stabilizing or disruptive part of an organization’s operations, based on frequency of principal changes. So a principal in a contracting partnership must balance the need for accountability and flexibility through frequent contracting, with the partner/agent’s need for adjustment and operational process norming through less frequent contracting (Milward and Provan 1993). Stability concerns were found to be an important variable in several empirical network studies in the past decade. Provan and Milward (1995) found 8 that mental health networks had improved effectiveness if there were stability related to the Network Administrator and their connections with the state. Likewise, Isett and Provan (2005) illustrated that networks may also have stable network structures, which helps to smooth out operations by having a stable roster of organizations with which an organization interacts, consistent with the buffering core technologies and pre-empting environmental uncertainty concepts discussed above. The vulnerabilities created by turbulence in the environment are enacted. Just as organizations enact their environments, choosing which elements to pay heed to and to address, they enact their vulnerabilities as well. Organizations will choose to perceive vulnerabilities that they feel are important. More importantly, however, is that the vulnerabilities themselves are perceived (Van de Ven and Walker 1984). One such vulnerability that has been increasingly cited in the new institutional literature is legitimacy. Vulnerabilities, or perceptions of vulnerabilities, are an important reason for organizations to come together. While most vulnerabilities and uncertainties have some tangible quality to them, the conferring of organizational legitimacy is one organizational resource in which the focal organization has little control of acquisition. Organizational legitimacy is the idea that other actors in the organizations environment accept the organizations actions, processes and outcomes as appropriate (Suchman 1995; Zucker 1991). Legitimacy is socially conferred from outside the organization and can not be manufactured from within (Zucker 1991). 9 Thus, the organization is dependent upon others in their environment to bestow legitimacy upon them. One way that some organizations approach legitimacy acquisition is through developing relationships with other organizations. This strategy is consistent with upward appeal activities of organizations where being associated with a prestigious alter organization produces a halo effect for the ego organization (Stinchcombe, 1965). Not only does this organizational behavior produce some legitimacy effects, it also helps the organization to overcome some of its inherent liabilities, such as newness and size (Stinchcombe 1965; Powell, Koput and Smith-Doerr 1996). Legitimacy is a powerful attribution and can impact organizational outcomes. Tolbert and Zucker (1983) illustrate the pressures to adopt civil service reform among public agencies in order to achieve or retain legitimacy. Early adopters became organizational and field leaders, while late adopters experienced pressures to mimic the successes of those governments with the reform already implemented. However, while Tolbert and Zucker illustrated the power of adopting innovative reform, it is less obvious that the reform itself must attain a level of legitimacy itself before adoption is viewed as desirable. Human and Provan (2000) demonstrate the power of legitimacy for innovations. In their study of two small manufacturing networks, they show how legitimacy works on three levels in network: network as interaction, network and entity, and network as form. If any of these three levels of legitimacy is not satisfied, then the network will not be effective, and will likely disband. Thus, 10 organizational legitimacy, in this case network legitimacy, is directly related to organizational survival. One way that legitimacy can be developed by an organization is through the building of reputation. Reputation is the idea that alters can predict reliably future or current behavior based on past behavior (Ostrom 1990). Alters can predict behavior based on a pattern that and ego has established in past or repeated interactions. Reputation attributions are stronger the longer established and the more consistent a pattern of behavior is. Thus, reliability is, more or less, the reliability that other have in predicting an ego’s behavior. Reputation is not quickly established, but rather is established over time. Organizations must engage in repeated interactions with the same partners (Gulati 1996; Uzzi 1997), or repeat the same interaction with multiple partners in order to establish the necessary accumulation of behavioral patterns to be recognized and used for prediction. Often, reputation is tied to legitimacy in that interpretation of reputation stems from conforming to ideas of what actions are appropriate in a particular setting. Thus, in some sense, reputation is related to the development of operational norms within a network or interorganizational relationships. Within any given social situation, norms of interaction and behavior will emerge. This signals to the actors in the social context that there is accepted ways to approach interaction. These accepted ways of interacting conveys shared meanings and interpretations of the social situation (Ostrom 1998). 11 Norms of interaction often develop through repeated interactions where actors in the social context begin to react to a stimulus in consistent ways. In this way the initiator of the interaction reads a signal that is either positive, indicating permissive behavior, or sanction, indicating prohibited behavior. Once these responses become consistent and systematized throughout the social context (in our case, a network), then these reactions are normative. Operational norms in a new social context, such as in a newly formed network, can be developed in two main ways. First, these norms can be newly created and go through a process of development, introduction, and acceptance, such as in Axelrod’s illustration of the norming of a “tit for tat” strategy (Axelrod 1981). Or second, norms may be appropriated from other social contexts (Heikkila and Isett 2004) and applied to the new setting. However, when this occurs, there is still a period where the norms must go through an acceptance period by the other network members. The development and acceptance of norms in a network may be facilitated through isomorphic processes (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). Mimetic isomorphism for norms can take place in two ways in a network. First, networks can mimic other networks which they desire to emulate by adopting their operations practices and processes. Second, some members of a network may adopt the practices and processes of a particular prestigious network member, thus accepting their normative rules and strategies for the entire group. Isomorphism may also be influenced by professional organizations’ expectations 12 for behavior, thereby imposing a professional ethic onto a network through normative isomorphism. No matter the way in which networks or interorganizational relationship partners develop their operational norms, these norms create the day-to-day operational rules and heuristics that members use in interacting with one another. If disturbances to the network operating environments occur and norms need to be adjusted, this is a slow process that will occur slowly and will require and alignment of operational, policy, and environmental factors (Isett, Morrissey and Topping, forthcoming; Heikkila and Isett 2004). Norm building, reputation, and reputation effects are all greatly facilitated by communication among organizational partners. A consistent finding in the social science literature is that communication among partners greatly increases commitment to collective goals and affects the functioning of the relationships within those partnerships (Ostrom 1998). Communication helps to spread norms and reputation, as well as affecting the resolution of uncertainty and contingencies. One way that terms of relationships are often communicated in their initial stages are through legal contracts. These contracts specify what each of the partners should do in the relationships and the compensation for compliance or penalties associates with non-compliance or default. Contractual relationships are ubiquitous throughout the management literature on interorganizational relationships (Uzzi 1997, Gulati 1998; Larson 1992; Isett and Provan 2005). 13 However, as relationships are repeated and organizations begin to discuss the solving of contingencies, rather than relying on a legalistic framework, relationships become embedded and the terms of the contracts may become more vague, relying more on communication. Relationships characterized by this embeddedness (Uzzi 1997) exchange proprietary knowledge and relationships have more specificity to the needs to their partners. Obviously, this is an intense relationships that requires large amounts of resources to develop. However, network governance structures are an effort to reduce those transactions costs of relationship development and acquiring embeddedness (Isett and Provan 2005). As has been shown in the game theory, experimental economics, and common pool resource literatures, “cheap talk” is a very effective way to gain compliance and communicate emerging norms and rules to network members. The concept of cheap talk is basically the informal interactions among members of collective groups. Further, Ostrom (1998) shows that face-to-face communication is more binding than more anonymous interactions such as memos and emails. A common theme that emerges in all of the management literature that deals with interorganizational relationships and networks is that relationships change over time. Time is a critical factor in developing the operational dynamics of a network. Human and Provan (2000) show that initial network efforts will be directed at gaining legitimacy from its members and from its environments Time works to build a pool of information on the network 14 members, as well as the network itself. This information decreases uncertainty for network members and helps to stave off additional turbulence potentially created by the network. Although time has been cited in most of the IOR literature, only a few articles have actually looked at the evolutionary dynamics of networks. Work by Provan and colleagues explicitly look at how the structural aspects of networks change over time and the implications of this change for service delivery in a network servicing adults with severe mental illness (Provan Isett and Milward 2004; Provan, Milward and Roussin 1998). Isett and Provan (2005) then go on to assess the changes of linkages within a network and the coercive isomorphic pressures that i9nfluence the changes in linkages over time. Model Development Figure 1 presents a model of interorganizational network formation based on the literature reviewed above. Although the IOR literature is well developed and suggests numerous factors that impinge upon interorganizational relationships, the factors that affect interorganizational network formation are somewhat different, albeit they build from the IOR concepts. At the top of the model there are four factors that are relevant for interorganizational network formation. These factors are reciprocity, legitimacy, stability, and resources. Reciprocity is the only factor that is a necessary condition for network formation, however, the other three factors are facilitating 15 factor. These facilitating factors can be present at the time of network formation or can be developed in the early stages of the network. Reciprocity is a necessary factor in network formation. As networks are formed, organizations come together in order to accomplish collective goals. These are goals that require input from other organizations, and that no single organization can produce itself at a reasonable cost to that organization. Thus, the organizations come together to capture the benefits of other organizations’ structures (Powell, Kpout, and Smith-Doerr 1996), and the benefits of participating in the network are outweighed by the costs (Provan 1983). If an organization is not invested in the goals or potential outcomes of the network, there will be a disincentive to work toward the goals of the network over individual pursuits. The three other factors at the top of the model are facilitators of network formation. While these three factors are not necessary to formation, they greatly facilitate it. Further, if these factors are not present at the time of network development they may become issues or develop early in the network formation process. The first of these facilitating factors is legitimacy. Legitimacy is sought for the long tern viability of an organization, including network forms of organization. While the conferring of on a network legitimacy in any of the ways noted by Human and Provan (2000) (form, entity, or interaction) is not a prerequisite for network formation, legitimacy must be achieved at some point in order to acquire 16 resources from its members and its environment. Otherwise, the network organization will not be viable –as with organizations. The second of the facilitating factors is a contextual in nature –stability. The political, cultural, and operating environments in which the network seeks to form must have sufficient stability so that the network organizers can focus on and facilitate coordination and cooperation. While this is not absolutely necessary –since the network may be an attempt to bring order to chaos - some stability in the three environments would lend to the development of the trust and communication that are necessary to create cohesive collective action. Otherwise, with excessive instability, individual organizations may be too distracted putting out their own fires to fully pay attention to or address issues of collective governance and norm building, as needed in anew network entity. The final facilitating factor is also contextual: resources. Many IORs and networks form out of the need to address resource scarcity (Aiken and Hage 1968). However, if there is not at least a minimal level of resources available for network formation –time, money, and/or human resources –then network formation and viability will be tenuous. The actual amount of minimal resources needed for a network tog et off the ground will be varied and will depend upon scope and scale of network activities, and the type of network/network structure chosen. These four factors, one necessary and three facilitating factors, are the precursors for the collective action necessary to create a network. These factors can come together to create a network. However, the simple presence of these 17 factors does not mean a network will be created, just that it may. There are two causes of network formation that must be present for a network to form: will and knowledge. First, the will must be there to create a network. A network is a social unit of organization. Actors, in our case organizations, must desire to come together and work collectively. This desire may be organic –as in many bottom-up networks that form (see the CPR literature, especially Ostrom and colleagues’ work). It may be imposed –as in many government funded service delivery network (see the mental health literature, especially the results of the ACCESS study by Morrissey and colleagues). Or it may be some combination of the two (especially the work of Provan and colleagues). Although the desire may come from many places, it must be present in order for the network formation to occur. Will also encompasses the classic idea of collective action: that actors must be willing to voluntarily act to further their interests in collective goals and activities (Ostrom 1990), while also avoiding the temptation to free ride on the activities of others. There must be a conscious collectivity of a broader governing logic for a network to be present. Otherwise, the partnerships are merely a series of dyadic, atomistic relationships. In other words, there must be a will to coordinate. Second, there must be knowledge that the factors exist in order to form the network. If an organization does not know that other organizations exist that have complementary products and services to accomplish a goal, or even who those organizations are, then it is not likely that the organization will see a 18 partnership with those organizations. An analogy to clarify this point is if you do not know that you have eggs in the refrigerator, it doe not matter that you have flour in cupboard. You just will not think of baking a cake, or that baking a cake is possible given current resources. So, assuming that the necessary formation factor of reciprocity is present, there is sufficient will and knowledge to form a network, and the facilitating factors are present in varying degrees (including not at all), then a network may form. Organizations can come together to form a network. However, there are some important transformation processes that must occur in order for a network to pass the threshold of burgeoning/neophyte to an operational network. The evolution from a neophyte network to an actual operating network is a process that develops communication, norms appropriate to incentives, and reputation over time. Time is the essential characteristic in this transformation. It has been well documented that norms are very slow to evolve, as well as reputation and trust effects to occur. All of this happens through increased and repeated interaction where communication is open and facilitated. Several strain of literature support this emphasis of time. Common Pool Resource and Game Theory scholars have shown that actors facing a social dilemma will adjust their strategies over time to achieve the best possible outcomes (Axelrod 1981, 1984; Ostrom 1990, 1998). Further, organization theorists have shown that time is a critical factor in the development of sustainable relationships between organizations (Gulati 1995; Larson 1992; Uzzi 1997; Van de Ven and Walker 1984). 19 In the laboratory and in field settings, communication has been shown to enable the resolution of commons problems (Ostrom 1990) and in sustainable IORs (Larson 1992; Gulati 1995; Uzzi 1997; Van de Ven and Walker 1984). Communication helps to facilitate the exchange of ideas, proprietary knowledge, and future strategy intentions between actors in a collective action situation (Larson 1992; Ostrom, Gardner and Walker 1994; Van de Ven and Walker 1985). This communication assists actors in reducing their perceptions of their core vulnerabilities as well as aiding others in predicting future outcomes (Lazerson 1995; Ostrom 1990, 1998; Uzzi, 1997). As stated by Ostrom (1998, 7), “exchanging commitment, increasing trust, creating and reinforcing norms, and developing a group identity appear to be the most important processes that make communication efficacious.” One way in which group identity is created is through shared norms. However, norms must be consistent with and enhance the incentive structures in an operational network. Misalignment of norms and incentives could work to impede achievement of network objectives. Social learning takes place among the members of a network in how to behave, as well as how to interpret and act upon the formal legal structures of the network. When adequate social and legal guides are in place (through incentives and norms) the temptation to free ride or behave counter to the collective goals is reduced. This reduction of deviant behavior creates an opportunity to realize collective goals and outcomes for the network. 20 Reputation that can develop into trust is perhaps one of the most widely cited factors in creating viable IORs and IONs. Consistent interactions with other actors create predictable future behavior (Gulati 1995; Ostrom 1990; Uzzi 1997). This consistency creates reputation for those outside the relationship, and trust for those more involved in the relationship. Once reputation is established, commitments to behave in a particular manner become viewed as credible, and the transactions costs of interactions then decline (Isett and Provan 2005). Reputation will become enhanced or devalued as communication allows others to make judgments about the credibility of other actors’ intentions (Gulati 1995; Ostrom 1998). Thus, reputation and trust emerges in a network when promises from one actor to take certain actions are accepted at face value or become embedded in the pattern of the relationship (Uzzi 1997) by other actors. The transformation stage of operational network formation varies by network, and may never actually yield a viable network. The time that transformation takes will be unique to each network and will depend on a number of variables such as number of members, scope and scale of operations, existing history among members, and the like. However, once the transformation begins, patterns of interaction will begin to emerge. Once these patterns stabilize and governance issues are settled, an operational network emerges. It is important to note that not all networks will reach viability and become operational. Many networks will languish for years in the transformation stage and never really emerge as an operational entity. Also, while outcomes may be accomplished during the transformation stage, the focus is on governance and 21 development issues, not the network goal. While these networks clearly have outputs, they are not viable in that trust and norm alignment has not occurred. Until viability is achieved, network will likely only produce outputs, not outcomes. Conclusion This model is a first look at how organizations come together to form interorganizational networks. In this paper I have attempted to outline the theoretical and conceptual elements of the existing literature that have framed my thinking on interorganizational network formation. This paper has also attempted to delineate where the networks literature differs or develops differently from the literature focused on dyads or organizational sets. As such, a model has been presented and developed to conceptualize how networks form, why some become viable, and the elements which are a harbinger of dissolution and failure. 22 References Aiken, M. and J. Hage. 1968. Organizational Interdependence and Intraorganizational Structure. American Sociological Review. 33: 912930. Alter, C. and J. Hage. 1993. Organizations Working Together. Newbury Park: Sage. Axelrod, R. 1984. The Evolution of Cooperation. New York: Basic Books. Axelrod, R. 1981. The Emergence of Cooperation Among Egoists. American Political Science Review 75: 306-318. Chisholm, R.F. 1998. Developing Network Organizations: Learning from Practice and Theory. Reading: Addison-Wesley. Dill, A.E.P. and D. A. Rochefort. 1989. Coordination, Continuity, and Centralized Control: A Policy Perspective on Service Strategies for the Chronic Mentally Ill. Journal of Social Issues. 45(3): 145-159. DiMaggio, P.J. and W.W. Powell. 1983. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review. 48: 147-160. Galaskiewicz, J. 1985 Interorganizational Relations. Annual Review of Sociology 11: 281-304. Gulati, R. 1995. Does Familiarity Breed Trust? The Implications of Repeated Ties for Contractual Choice in Alliances. Academy of Management Journal. 38: 85-112. Heikkila, T. and K.R. Isett. 2004. Developing a Model of Institutional Choice: The Advantages of a Cross-Disciplinary Approach. American Review of Public Administration 34(1): 3-19. Human, S.E. and K.G. Provan. 2000. Legitimacy Building in the Evolution of Small-Firm Multilateral Networks: A Comparative Study of Success and Demise. Administrative Science Quarterly 45(2): 327-365. Isett K.R., J.P. Morrissey, and S. Topping. Managed Care in a Public System: Caregivers’ Perceptions about Quality of Care and Service Delivery. Public Administration Review. Forthcoming. 23 Isett, K.R. and K.G. Provan. 2005 The Evolution of Dyadic Interorganizational Relationships in a Network of Publicly Funded Nonprofit Agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 15: 149-165. Larson, A. 1992. Network Dyads in Entrepreneurial Settings: A Study of the Governance of Exchange Relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly. 37: 76-104. Lazerson, M. 1995. A New Phoenix?: Modern Putting-out in the Modena Knitwear Industry. Administrative Science Quarterly. 40 (1995): 34-59. Milliken, Frances J. 1987. Three types of uncertainty about the environment: State, effect, and response uncertainty. Academy of Management Review, 12(1): 133-143. Milward, H.B. and K.G. Provan. 2000. Governing the Hollow State. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 10(2): 359-379. Milward, H.B. and K.G. Provan. 1993. The Hollow State: Private Provision of Public Services. Public Policy for Democracy. Eds. Ingram and Smith. Washington: Brookings. 222-237. Oliver, C. 1990. Determinants of Interorganizational Relationships: Integration and Future Directions. Academy of Management Review. 15(2): 241265. Ostrom, E. 1998. A Behavioral Approach to the Rational Choice Theory of Collective Action: Presidential Address, American Political Science Association, 1997. American Political Science Review. 92(1): 1-22. Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Ostrom, E., R. Gardner, and J. Walker. 1994. Rules, Games, & Common-Pool Resources. An Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Powell, W.W. 1990. Neither Market nor Hierarchy: Network Forms of Organization. Research in Organizational Behavior 12: 295-336. Powell, W. W., et al. 1996. Interorganizational Collaboration and the Locus of Innovation: Networks of Learning in Biotechnology. Administrative Science Quarterly. 41 (1996): 116-145. Provan, K.G. 1983. The Federation as an Interorganizational Linkage Network. Academy of Management Review 9: 79-89. 24 Provan, K.G., K.R. Isett and H.B. Milward. 2004. Cooperation and Compromise: Conflicting Institutional Pressures on Interorganizational Collaboration. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 33(3): 489-514. Provan, K. G. and H. B. Milward. 1995. A Preliminary Theory of Interorganizational Network effectiveness: A Comparative Study of Four Community Mental Health Systems. Administrative Science Quarterly 40: 1-33. Provan, K. G., H. B. Milward, and K. Roussin. 1998. Network Evolution to a system of Managed Care for Adults with Serious Mental Illness: A case Study of the Tucson Experiment. In Research in Community and Mental Health. J. P. Morrissey (ed.) 9: 89-113. Sabel, C.F. 1989. Flexible Specialisation and the Reemergence of Regional Economies. In Reversing Industrial Decline. Hirst and Zeitlin eds. Berg. 17-69. Scott, J. 1991. Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. London: Sage. Stinchcombe, A. L. 1965. Social Structure and Organizations. In Handbook of Organizations J.G. March (ed.). New York: Rand McNally. 142-193. Suchman, M. C. 1995. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Academy of Management Review. 20(3): 571-610. Thompson, J.D. 1967. Organizations in Action. New York: McGraw-Hill. Tolbert, P.S. and L.G. Zucker. 1983. Institutional Sources of Change in the Formal Structure of Organizations: The Diffusion of Civil Service Reform, 1880-1935. Administrative Science Quarterly. 28: 22-39. Uzzi, B. 1997. Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly. 42:35-67. Van De Ven, A.H. and G. Walker. 1984. The Dynamics of Interorganizational Coordination. Administrative Science Quarterly. 29: 598-621. Zucker, L. 1991. The Role of Institutionalization in Cultural Persistence. In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Eds. Powell and DiMaggio. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago. 83-107. 25 Figure 1 A Model of Operational Interorganizational Network Formation Network PreConditions legitimacy stability reciprocity Neophyte/Burgeoning resources will and knowledge Transformation time communication Norms reputation Viability operational network 26