THE CREDIT MONEY, STATE MONEY, AND ENDOGENOUS INTEGRATION

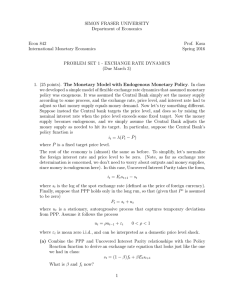

advertisement