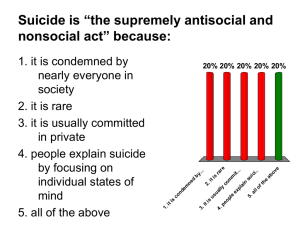

ff e c tive ne ss of L e

advertisement