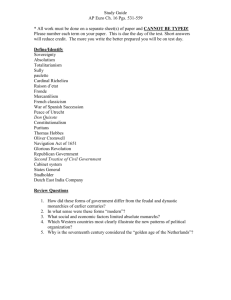

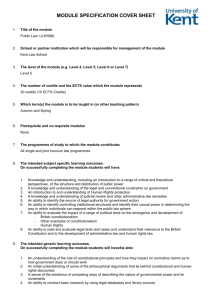

Constitutionalism and the New Forms of Power

advertisement