Name:___________________________________ Date:_________________ Period:______

advertisement

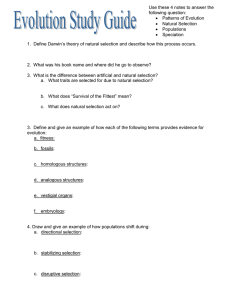

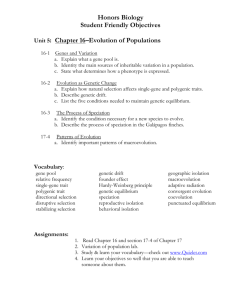

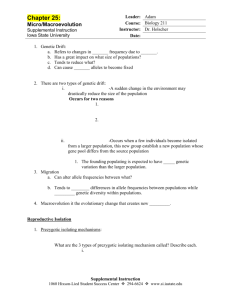

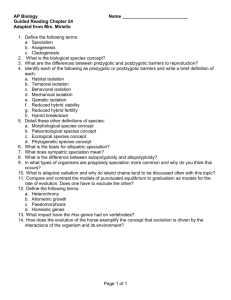

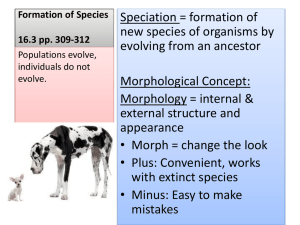

Name:___________________________________ Date:_________________ Period:______ This reading guide covers text pages 418 – 449. It is aligned with California state Biology/Life Science standards 7a-7d and 8a-8e. After reading the above pages and completing this reading guide you should be familiar with the following vocabulary: Adaptation Adaptive radiation Allopatric speciation Allelic frequency Analogous structure Artificial selection Bottleneck effect Camouflage Convergent evolution Directional selection Disruptive selection Divergent evolution Embryo Founder Effect Gene pool Genetic drift Genetic equilibrium Geographic isolation Gradualism Homologous structure Mimicry Natural selection Polyploidy Pre-zygotic barriers Post-zygotic barriers Punctuated equilibrium Reproductive isolation Species Speciation Stabilizing selection Sympatric speciation Vestigial structure The following assignments will be collected in one week. 1. The book gives five evidences support evolution and a description of artificial selection. Make a chart listing these six and give a description of each. 2. Write one paragraph explaining the differences between artificial selection and natural selection. It will be easier if you include specific examples. Use complete sentences. 3. Given that variation within a species increases the likelihood that at least some members of a species will survive under changed environmental conditions, in one paragraph explain how variation can improve survival. a. Discuss how variation is produced via mutation or genetic recombination b. Discuss how some traits enable organisms to adapt more successfully to their environment with examples. c. Define survival in terms of capacity to adapt, avoid predation and produce offspring. 4. How are the two types of adaptations cited in the book beneficial to increasing fitness? 5. The Hardy-Weinberg principle states that allele frequencies in a population should be constant. Work through the example of earlobe attachment in the textbook. Next cite the conditions that must be present if Hardy-Weinberg principle is to hold true. 6. Describe what genetic drift is in general and two extreme examples: founder effect and bottleneck effect; give examples as to how both extreme examples occur. 7. Make a chart listing and describing the three different types of natural selection (stabilizing, directional, and disruptive) that act on variation. In your chart, include a graph and an example of each type. 8. What are three factors that can cause speciation? 9. Different patterns of evolution occur throughout the world in different natural environments. These patterns support the idea that natural selection is an important agent for evolution. Describe the three patterns that are discussed in the book and give an example of each. 10. What is the usual rate of speciation? Describe the two hypotheses proposed that deal with this question. Industrial Melanism: the peppered moth example of natural selection1 The peppered moth (Biston betularia) comes in two forms and the difference between the two forms of moth is controlled by a pair of alleles at a single chromosome locus. The light-colored form of the peppered moth, known as typica, was the predominant form in England prior to the beginning of the industrial revolution. Shown at left, the typica moth's speckled wings are easy to spot against a dark background, but would be difficult to pick out against the light-colored bark of many trees common in England. Around the middle of the 19th century, however, a new form of the moth began to appear. The first report of a dark-colored peppered moth was made in 1848. By 1895, the frequency in Manchester had reached a reported level of 98% of the moths. This dark-colored form of the peppered moth is known as carbonaria, and (as shown at right), it is easiest to see against a light background. As you can well imagine, carbonaria would be almost invisible against a dark background, just as typica would be difficult to see against a light background. The increase in carbonaria moths was so dramatic that many naturalists made the immediate suggestion that it had to be the result of the effects of industrial activity on the local landscape. Coal burned during the early decades of the industrial revolution produced soot that blanketed the countryside of the industrial areas of England between London and Manchester. Several naturalists noted that the typica form was more common in the countryside, while the carbonaria moth prevailed in the sooty regions. Not surprisingly, many jumped to the conclusion that the darker moths had some sort of survival advantage in the newly-darkened landscape. In recent years, the burning of cleaner fuels and the advent of Clean Air laws has changed the countryside even in industrial areas, and the sootiness that prevailed during the 19th century is all but gone from urban England. Coincidentally, the prevalence of the carbonaria form has declined dramatically. In fact, some biologists suggest that the dark forms will be all but extinct within a few decades. Draw a picture showing how differential predation by birds was the selective pressure involved in this natural selection example. 1 http://www.millerandlevine.com/km/evol/Moths/moths.html and http://www.smccd.net/accounts/bucher/indumeli.pdf Genetic Drift2 Genetic drift—along with natural selection, mutation, and migration—is one of the basic mechanisms of evolution. In each generation, some individuals may, just by chance, leave behind a few more descendents (and genes, of course!) than other individuals. The genes of the next generation will be the genes of the “lucky” individuals, not necessarily the healthier or “better” individuals. That, in a nutshell, is genetic drift. It happens to ALL populations— there’s no avoiding the random results of chance. Genetic drift affects the genetic makeup of the population but, unlike natural selection, through an entirely random process. So although genetic drift is a mechanism of evolution, it doesn’t work to produce adaptations. Genetic drift and natural selection rarely occur in isolation of each other; both forces are always at play in a population. However, the degree to which alleles are affected by drift and selection varies according to circumstance. In a large population, where genetic drift occurs very slowly, even weak selection on an allele will push its frequency upwards or downwards (depending on whether the allele is beneficial or harmful). However, if the population is very small, drift will predominate. In this case, weak selective effects may not be seen at all as the small changes in frequency they would produce are overshadowed by drift. Diagram examples of genetic drift in a small population and a large population. Remember to give some numbers for gene frequencies in your examples. 2 http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/evo101/IIID2Genesdrift.shtml What Causes Speciation?3 Speciation, or the evolution of reproductive isolation, occurs as a by-product of genetic changes that accumulate between two previously interbreeding populations of the same species. For example, let us start with two populations of the same species that do not differ genetically. Initially, an individual from population A is able to successfully breed with an individual from population B. As these populations evolve, they each gradually accumulate genetic changes that are different from the other populations' genetic changes. In other words, the two populations genetically diverge from each other. These changes can be due to different selection pressures because of different environments, or because of genetic drift/founder events. How does Speciation Occur? There are several different ways in which the evolution of reproductive isolation is thought to occur. These can, however, be generalized into a series of events, or steps. The "Steps" in a speciation event: Step 1: gene flow between two populations is interrupted (populations become genetically isolated from each other) Step 2: genetic differences gradually accumulate between the two populations (populations diverge genetically) Step 3: reproductive isolation evolves as a consequence of this divergence (a reproductive isolating mechanism evolves) The main difference between the different models of speciation is in the first step, or how the populations become genetically isolated from each other. Reproductive Isolation At some point in this process, some of these genetic changes cause the two populations to become reproductively isolated from each other. In other words, these genetic changes no longer allow an individual from population A to successfully breed with an individual from population B. They prevent gene flow between populations. These specific genetic differences that confer reproductive isolation are called reproductive isolating mechanisms. There are several different types of reproductive isolating mechanisms, which are classified according to when in the life cycle of the organism isolation occurs. Isolation can occur before fertilization (prezygotic barriers) or after fertilization (postzygotic barriers). Prezygotic isolation can occur either before mating occurs (premating barriers) or after mating occurs (postmating barriers). One type of premating prezygotic isolation occurs when potential mates from the two populations do not meet, either because they are separated in time (temporal isolation) or in space (habitat isolation). Temporal isolation can occur if individuals in two different populations mate at different times of the day or in different seasons, or even years (e.g. species of periodical cicadas mate either every 7 years or every 13 years). Habitat isolation occurs, for example, when herbivorous insects from two populations feed and mate on different host plants. Another type of premating prezygotic isolation occurs when individuals from two populations meet, but they do not mate (behavioral or sexual isolation). This occurs, for example, when courtship behaviors differ between individuals of two populations (e.g. songs in birds, pheromones in moths, light displays in fireflies, etc.). 3 http://evoled.dbs.umt.edu/lessons/speciation.htm#causes One type of postmating prezygotic isolation occurs when mating actually takes place, but male gametes are not actually transferred to the female (mechanical isolation). This happens when there is an anatomical incompatibility between individuals from two populations. For example, the floral anatomy of some plant species prevents some pollinators that visit the plant from actually transferring pollen. In this case, mating (pollination) occurs, but the male gametes (pollen) are not able to reach the eggs. A second type of postmating prezygotic isolation occurs after mating taking places, male gametes are actually transferred, but the egg is not fertilized (gametic isolation). This can be an important isolating mechanism in externally reproducing species that send out their gametes en masse. Sea urchins, for example, release their gametes into the water column. In reproductively isolated species, male and female gametes actually meet, but the sperm does not fertilize the egg. Another example of this would be when pollen from a plant of one species lands on the stigma of a plant from another species, and a pollen tube is not completely formed. In both of these cases, a genetic mismatch between the gametes prevents successful fertilization. There are three types of postzygotic isolating mechanisms. In the first type, mating occurs, a zygote is formed, but the hybrid has reduced viability (hybrid inviability). In other words, hybrids do not survive long enough to reproduce. The other type of postzygotic isolation occurs when hybrids are viable, but they have reduced fertility (hybrid sterility). A classic example is the mule, which is the result of a cross between a donkey and a horse. Mules are viable, healthy animals, but they are always sterile (i.e. they are unable to successfully reproduce). The third type of postzygotic isolation occurs when hybrids are viable and fertile, but the offspring of the hybrids are inviable or sterile (hybrid breakdown). In all of these postzygotic examples, individuals from the two populations will mate with each other, and the gametes fuse, but the genetic material in each of the gametes differs enough that the combinations of alleles are not compatible. http://videos.howstuffworks.com/wgbh-nova/13619-evolution-in-action-video.htm