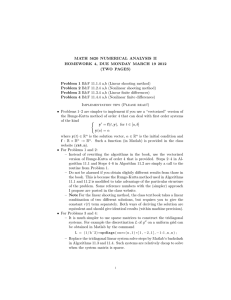

High-Performance Computation for Path Problems in Graphs Aydin Buluç John R. Gilbert

advertisement

High-Performance Computation for Path Problems in Graphs Aydin Buluç John R. Gilbert University of California, Santa Barbara SIAM Conf. on Applications of Dynamical Systems May 20, 2009 1 Support: DOE Office of Science, MIT Lincoln Labs, NSF, DARPA, SGI Horizontal-vertical decomposition [Mezic et al.] 2 Slide courtesy of Igor Mezic group, UCSB Combinatorial Scientific Computing “I observed that most of the coefficients in our matrices were zero; i.e., the nonzeros were ‘sparse’ in the matrix, and that typically the triangular matrices associated with the forward and back solution provided by Gaussian elimination would remain sparse if pivot elements were chosen with care” - Harry Markowitz, describing the 1950s work on portfolio theory that won the 1990 Nobel Prize for Economics 3 A few directions in CSC • • • • • • • • • • • • 4 Hybrid discrete & continuous computations Multiscale combinatorial computation Analysis, management, and propagation of uncertainty Economic & game-theoretic considerations Computational biology & bioinformatics Computational ecology Knowledge discovery & machine learning Relationship analysis Web search and information retrieval Sparse matrix methods Geometric modeling ... The Parallel Computing Challenge Two Nvidia 8800 GPUs > 1 TFLOPS LANL / IBM Roadrunner > 1 PFLOPS Parallelism is no longer optional… … in every part of a computation. 5 Intel 80core chip > 1 TFLOPS The Parallel Computing Challenge Efficient sequential algorithms for graph-theoretic problems often follow long chains of dependencies Several parallelization strategies, but no silver bullet: Partitioning (e.g. for preconditioning PDE solvers) Pointer-jumping (e.g. for connected components) Sometimes it just depends on what the input looks like 6 A few simple examples . . . Sample kernel: Sort logically triangular matrix Original matrix 7 Permuted to unit upper triangular form • Used in sparse linear solvers (e.g. Matlab’s) • Simple kernel, abstracts many other graph operations (see next) • Sequential: linear time, simple greedy topological sort • Parallel: no known method is efficient in both work and span: one parallel step per level; arbitrarily long dependent chains Bipartite matching 1 2 3 4 5 1 1 1 1 4 2 2 2 5 3 3 3 4 3 4 5 3 1 5 A 8 2 4 4 5 5 2 PA • Perfect matching: set of edges that hits each vertex exactly once • Matrix permutation to place nonzeros (or heavy elements) on diagonal • Efficient sequential algorithms based on augmenting paths • No known work/span efficient parallel algorithms Strongly connected components 1 2 4 7 5 1 3 6 1 2 4 7 2 4 7 5 5 3 PAPT 9 6 3 6 G(A) • Symmetric permutation to block triangular form • Diagonal blocks are strong Hall (irreducible / strongly connected) • Sequential: linear time by depth-first search [Tarjan] • Parallel: divide & conquer, work and span depend on input [Fleischer, Hendrickson, Pinar] Horizontal - vertical decomposition 1 level 4 9 8 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 2 6 level 3 3 7 4 5 level 2 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 level 1 1 9 • Defined and studied by Mezic et al. in a dynamical systems context • Strongly connected components, ordered by levels of DAG • Efficient linear-time sequential algorithms • No work/span efficient parallel algorithms known 10 Strong components of 1M-vertex RMAT graph 11 Dulmage-Mendelsohn decomposition 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 2 9 10 11 1 2 HR 3 4 5 6 7 SR 8 9 10 11 12 VR 1 3 2 4 3 5 4 6 5 7 6 8 7 9 8 10 9 11 10 11 12 12 HC SC VC Applications of D-M decomposition 13 • Strongly connected components of directed graphs • Connected components of undirected graphs • Permutation to block triangular form for Ax=b • Minimum-size vertex cover of bipartite graphs • Extracting vertex separators from edge cuts for arbitrary graphs • Nonzero structure prediction for sparse matrix factorizations Strong Hall components are independent of choice of matching 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 5 3 6 6 6 7 7 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 5 6 6 6 3 7 7 1 2 4 7 5 3 6 1 2 4 7 1 4 1 7 2 14 2 4 7 5 3 6 The Primitives Challenge • By analogy to numerical linear algebra. . . Basic Linear Algebra Subroutines (BLAS): Speed (MFlops) vs. Matrix Size (n) C = A*B y = A*x μ = xT y • 15 What should the “combinatorial BLAS” look like? Primitives for HPC graph programming • Visitor-based multithreaded [Berry, Gregor, Hendrickson, Lumsdaine] + search templates natural for many algorithms + relatively simple load balancing – complex thread interactions, race conditions – unclear how applicable to standard architectures • Array-based data parallel [G, Kepner, Reinhardt, Robinson, Shah] + relatively simple control structure + user-friendly interface – some algorithms hard to express naturally – load balancing not so easy 16 • Scan-based vectorized • We don’t know the right set of primitives yet! [Blelloch] Array-based graph algorithms study [Kepner, Fineman, Kahn, Robinson] 17 Multiple-source breadth-first search 1 2 4 7 3 AT 18 X 6 5 Multiple-source breadth-first search 1 2 4 7 3 AT 19 X ATX 6 5 Multiple-source breadth-first search 1 2 4 7 3 AT 20 X 6 ATX • Sparse array representation => space efficient • Sparse matrix-matrix multiplication => work efficient • Span & load balance depend on matrix-mult implementation 5 Matrices over semirings • Matrix multiplication C = AB (or matrix/vector): Ci,j = Ai,1B1,j + Ai,2B2,j + · · · + Ai,nBn,j • Replace scalar operations and + by : associative, distributes over , identity 1 : associative, commutative, identity 0 annihilates under 21 • Then Ci,j = Ai,1B1,j Ai,2B2,j · · · Ai,nBn,j • Examples: (,+) ; (and,or) ; (+,min) ; . . . • Same data reference pattern and control flow SpGEMM: Sparse Matrix x Sparse Matrix [Buluc, G] 22 • Shortest path calculations (APSP) • Betweenness centrality • BFS from multiple source vertices • Subgraph / submatrix indexing • Graph contraction • Cycle detection • Multigrid interpolation & restriction • Colored intersection searching • Applying constraints in finite element modeling • Context-free parsing Distributed-memory parallel sparse matrix multiplication j k 2D block layout Outer product formulation Sequential “hypersparse” kernel k * i = Cij Cij += Aik * Bkj • Asynchronous MPI-2 implementation • Experiments: TACC Lonestar cluster • Good scaling to 256 processors Time vs Number of cores -- 1M-vertex RMAT 23 All-Pairs Shortest Paths • Directed graph with “costs” on edges • Find least-cost paths between all reachable vertex pairs • Several classical algorithms with • – Work ~ matrix multiplication – Span ~ log2 n Case study of implementation on multicore architecture: – 24 graphics processing unit (GPU) GPU characteristics • Powerful: two Nvidia 8800s > 1 TFLOPS • Inexpensive: $500 each But: • Difficult programming model: One instruction stream drives 8 arithmetic units • Performance is counterintuitive and fragile: Memory access pattern has subtle effects on cost • Extremely easy to underutilize the device: Doing it wrong easily costs 100x in time 25 t1 t2 t3 t4 t5 t6 t7 t8 t9 t10 t11 t12 t13 t14 t15 t16 Recursive All-Pairs Shortest Paths Based on R-Kleene algorithm Well suited for GPU architecture: A A B C D D B • Fast matrix-multiply kernel • In-place computation => low memory bandwidth • Few, large MatMul calls => low GPU dispatch overhead • Recursion stack on host CPU, D = D + CB; D = D*; % recursive call not on multicore GPU • 26 C Careful tuning of GPU code + is “min”, A = A*; × is “add” % recursive call B = AB; C = CA; B = BD; C = DC; A = A + BC; Execution of Recursive APSP 27 APSP: Experiments and observations 128-core Nvidia 8800 Speedup relative to. . . 1-core CPU: 120x – 480x 16-core CPU: Iterative, 128-core GPU: 17x – 45x 40x – 680x MSSSP, 128-core GPU: ~3x Time vs. Matrix Dimension Conclusions: • High performance is achievable but not simple • Carefully chosen and optimized primitives will be key 28 H-V decomposition 1 level 4 9 8 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 2 6 level 3 3 7 4 5 level 2 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 level 1 1 9 A span-efficient, but not work-efficient, method for H-V decomposition uses APSP to determine reachability… 29 Reachability: Transitive closure 1 level 4 9 8 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 2 6 level 3 3 7 4 5 level 2 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 level 1 30 1 9 • APSP => transitive closure of adjacency matrix • Strong components identified by symmetric nonzeros H-V structure: Acyclic condensation level 4 8 9 1 2 3 6 8 9 1 67 level 3 2 3 level 2 2 345 6 8 9 level 1 31 1 • Acyclic condensation is a sparse matrix-matrix product • Levels identified by “APSP” for longest paths • Practically speaking, a parallel method would compromise between work and span efficiency Remarks 32 • Combinatorial algorithms are pervasive in scientific computing and will become more so. • Path computations on graphs are powerful tools, but efficiency is a challenge on parallel architectures. • Carefully chosen and implemented primitive operations are key. • Lots of exciting opportunities for research!