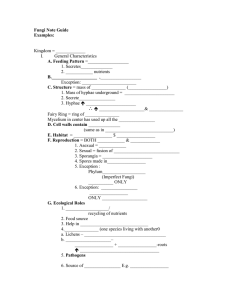

KINGDOM FUNGI

advertisement

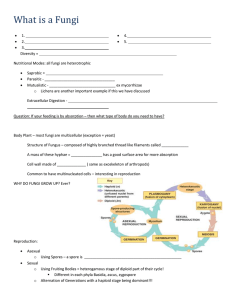

KINGDOM FUNGI The fungi are as distinct from the mosses and higher vascular plants as they are from the animals and are a distinct kingdom. There are about 100,000 species of fungi that have been described, and it is estimated that as many as 200,000 more may await discovery. There may actually be as many species of fungi as there are species of plants, although far fewer have been described thus far. The fungi have no direct evolutionary connection with the plants and apparently were derived independently from a different group of single-celled eukaryotes. The oldest fossils that resemble fungi occur in the strata about 900 million years ago, but the oldest that have been identified with certainty as fungi are from the Ordovician period, 450 to 500 million years ago. Representatives of Division Zygomycota were associated with the underground portions of the earliest vascular plants in the Silurian period, some 400 million years ago. Fungi may be among the oldest eukaryotes; the four major groups were in existence by the close of the Carboniferous period, some 300 million years ago. The fungi, together with the heterotrophic bacteria and a few other groups of organisms are the decomposers of the biosphere. Their activities are as essential to the continued functioning of the biosphere as are those of the primary producers. Decomposition releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and returns nitrogenous compounds and other minerals to the soil where they can be used again by the green plants and eventually the animals. It is estimated that, on the average, the top 20 centimeters of fertile soil may contain nearly 5 metric tons of fungi and bacteria per hectare (2.47 acres). As decomposers, fungi often come into direct conflict with human interests. A fungus that feeds on wood makes no distinction between a fallen tree in the forest or a railway tie. Equipped with a powerful arsenal of enzymes that break down organic products, fungi are often nuisances and are sometimes highly destructive. This is especially true in the tropics, where the warmth and dampness promote fungal growth. Fungi attack cloth, paint, leather, jet fuel, insulation on cables and wires, photographic film, and even the coating of the lenses of optical equipment in fact almost any conceivable substance. Even in temperate regions, they are the scourge of food producers and sellers alike. They can grow on bread, fresh fruits, vegetables, meats, and other products. Fungi reduce the nutritional value, as well as the palatability, of such foodstuffs. Some also produce extremely poisonous toxins, some of which - the aflotoxins - are extremely carcinogenic and show their effects at concentrations as low as a few parts per billion. Many fungi are pathogenic, and attack living organisms, rather than dead ones. They are the most important single cause of plant diseases. Well over 5000 species of fungi attack economically valuable crop and garden plants, as well as many wild plants. Other fungi are the cause of serious diseases in humans and other animals. Many fungi are commercially valuable. For example the yeasts, are useful because of their abilities to produce substances such as ethanol and carbon dioxide (which plays a central roll in baking). Others are of interest as sources of antibiotics, including penicillin, the first antibiotic to be widely used, and as potential sources of proteins. Associations between fungi and other organisms are extremely diverse. For example, about four-fifths of all land plants form associations between their roots and fungi called mycorrhizae. Mycorrhizae increase the absorptive surfaces of the plant roots and aid in mineral exchange between the soil and the plant. These associations play a critical role in plant nutrition and distribution. Basic Structure and Nutrition Some fungi exist as single cells and are known as yeasts. However, most species are multicellular. The basic structure of a fungus is the hypha (pl., hyphae)—a slender filament of cytoplasm and nuclei enclosed by a cell wall (Figure 9). A mass of these hyphae make up an individual organism, and is collectively called a mycelium. A mycelium can permeate soil, water, or living tissue; fungi certainly seem to grow everywhere. In all cases the hyphae of a fungus secrete enzymes for extracellular digestion of the organic substrate. Then the mycelium and its hyphae absorb the digested nutrients. For this reason, fungi are called absorptive heterotrophs. Heterotrophs obtain their energy from organic molecules made by other organisms. Fungi feed on many types of substrates. Most fungi obtain food from dead organic matter and are called saprophytes. Other fungi feed on living organisms and are parasites. Many of the parasitic fungi have modified hyphae called haustoria (Figure 9), which are thin extensions of the hyphae that penetrate living cells and absorb nutrients. Hyphae of some species of fungi have crosswalls called septa that separate cytoplasm and nuclei into cells. Hyphae of other species have incomplete or no septa (i.e., are aseptate) and therefore are coenocytic (multinucleate). The cell walls of fungi are made of chitin, the same polysaccharide that comprises the exoskeleton of insects and crustaceans. Figure 9: Basic structure of fungus. Reproduction in Kingdom Fungi Reproduction in fungi can be sexual or asexual. Many, but not all, fungi reproduce both sexually and asexually. Some reproduce only sexually, others only asexually. All divisions, however, share similar patterns of reproduction and morphology. a) Asexual Reproduction Fungi commonly reproduce asexually by mitotic production of haploid vegetative cells called spores in sporangia, and conidia on conidiophores. Spores are microscopic and surrounded by a covering well suited for the rigors of distribution into the environment. Budding and fragmentation are two other methods of asexual reproduction. Budding is mitosis with an uneven distribution of cytoplasm and is common in yeasts. After budding, the cell with the lesser amount of cytoplasm eventually detaches and matures into a new organism. Fragmentation is the breaking of an organism into one or more pieces, each of which can develop into a new individual. b) Sexual Reproduction The sexual cycle of fungi includes the familiar events of vegetative growth, genetic recombination, meiosis, and fertilization. However, the timing of these events is unique in fungi. Fungi reproduce sexually when hyphae of two genetically different individuals of the same species encounter each other. Following are the four important features of the sexual cycle of fungi: Nuclei of a fungal mycelium are haploid during most of the life cycle. Gametes are produced by mitosis and differentiation of haploid cells rather than directly from meiosis of diploid cells. Meiosis quickly follows formation of the zygote, the only diploid stage. Haploid cells produced by meiosis are not gametes; rather they are spores that grow into a mature haploid organism. Recall that asexual reproduction produces spores by mitosis. In both cases, haploid spores grow into mature mycelia. The union of the cytoplasm of two parent mycelia is known as plasmogamy. The union of two haploid nuclei contributed by two parents is known as karyogamy. Consider the following diagram, which illustrates the generalized life cycle of fungi. Classification of Fungi The taxonomy of fungi is currently the subject of much research. Although there is considerable discrepancy in the classification of fungi, we will treat the kingdom as having 3 divisions (phyla): the Zygomycota, Ascomycota, and Basidiomycota. Note, that the terms phylum and division can be used interchangeably. Where the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota are considered the "higher fungi", the other division is known as the "lower fungi", because they have retained many primitive characteristics. The separation of the 3 divisions in our system is based on reproductive structures. The Zygomycota (or zygote fungi) produce "zygospores" (heavy walled zygotes not associated with an oogonium), as their sexual reproductive spores. The Ascomycota (or sac fungi) produce "ascospores", within a special structure termed an ascus. The Basidiomycota (or club fungi) produce "basidiospores" in a basidium. As you examine members of these major groups, carefully note variations on the fundamental structure of vegetative mycelia and specialized structures associated with sexual and asexual reproduction. Division (Phylum): : Zygomycota Most of the Zygomycota live on decaying plant or animal matter in the soil but some are parasites on plants, insects or small soil animals. There are approximately 750 described species of Zygomycota. The term "Zygomycota" refers to the chief characteristic of the division; the production of sexual resting spores called “zygospores”. Most zygomycetes are saprophytic and their vegetative hyphae lack septa (i.e., they are aseptate). One representative of this division, Rhizopus stolonifera, a common black bread mold Rhizopus stolonifera (black bread mold) This species is one of the most common members of this division. This organism causes the black bread mold that forms cottony masses on the surface of moist bread exposed to the air. Asexual reproduction in Rhizopus occurs by spores (Figure 12). The mycelium of R. stolonifera is composed of three different types of haploid hyphae (another word for a filament). The bulk of the mycelium consists of rapidly growing submerged hyphae that are coenocytic (multinucleate) and aseptate (not divided by cross walls into cells or compartments). From the submerged hyphae, aerial hyphae called, stolons, are formed. The stolons form rhizoids wherever their tips come in contact with the substrate. Sporangia form on the tips of sporangiophores, which are erect branches formed directly above the rhizoids (Figure 10, 12). The sporangiophores support the asexual reproductive structures: the sporangia. Within a sporangium, haploid nuclei divide by mitosis and produce haploid spores. The cell wall that forms around each spore is black, giving the mold its characteristic color. The spores are released to the environment when the sporangium matures and breaks open. Each spore can germinate to produce a new mycelium. Diagram illustrating the vegetative and asexual reproductive structures of Rhizopus sp. Rhizopus sp. growing on peaches. (Asexual sporangiouphores) Sexual reproduction in Rhizopus occurs only between different mating strains, which have been traditionally labeled as + and – types (or Strain 1 and Strain 2, as seen in Figure 12). Although the mating strains are morphologically indistinguishable, they are often shown in life cycle diagrams as different colors). When the two strains are in close proximity, hormones are produced that cause their hyphal tips to come together and develop into gametangia (Figure 11, 12), which become separated from the rest of the fungal body by the formation of septa. The walls between the two touching gametangia dissolve, and the two multinucleate protoplasts come together. The + and - nuclei fuse in pairs to form a young zygospore with several diploid nuclei. The zygospore then develops a thick, rough black coat and becomes dormant, often for several months. Meiosis occurs at the time of germination. The zygospore cracks open and produces a sporangium that is similar to the asexually produced sporangium, and the life cycle begins again. Rhizopus stolonifera reproduces by sexual reproduction (gametangia, sporangia, & zygospores). Rhizopus stolonifera, sporangium. Rhizopus stolonifera, gametangia. Rhizopus stolonifera, young zygospore. Rhizopus stolonifera, a thick-walled zygospore. Pictures illustrating the stages of sexual reproduction. The life cycle of Rhizopus stolonifera (black bread mold). B) Division (Phylum): Ascomycota The Ascomycota comprise about 60,000 described species, including a number of familiar and economically important fungi. Most of the bluegreen, red, and brown molds that cause food spoilage are Ascomycota. This includes the salmon-colored bread mold Neurospora sp., which has played an important role in the development of modern genetics. Many Ascomycota are the cause of serious plant diseases, including powdery mildews that attack fruits, chestnut blight, and Dutch elm disease (caused by Ceratocytis ulmi, a fungus native to certain European countries). Yeasts, the edible morels and truffles are also Ascomycota. This group of fungi, as a whole, is relatively poorly known, and thousands of additional species await scientific description. Ascomycota, with the exception of the unicellular yeasts, are hyphal. The hyphae are septate, or divided by cross walls. The hyphal cells of the vegetative mycelium may be either uninucleate or multinucleate. Some species of Ascomycota can self-fertilize and produce sexual structures from a single genetic strain; others require a combination of + and - strains. 1) Asexual reproduction in the majority of the Ascomycota occurs by the formation of specialized spores, known as "conidia" (a Greek word for "fine dust"), which are cut off from tips of modified hyphae called "conidiophores"("conidia bearers"). The conidiophores partition conidia in longitudinal chains. Each conidium contains one or more nuclei. Conidia form on the surface of conidiophores in contrast to spores that form within sporangia in Rhizopus. When mature, conidia are released in large numbers and germinate to produce new organisms. Pencillium sp., which you will examine in this laboratory, is a common example of a fungus that forms conidia. 2) Sexual reproduction in Ascomycota always involves the formation of an "ascus" (pl. asci), a sac-like structure that is characteristic of this division and distinguishes the Ascomycota from all other fungi. Ascus formation is usually within a complex structure composed of tightly interwoven hyphae the "ascocarp". Many ascocarps are macroscopic, and are the only part of these fungi that most people ever see. An ascocarp may be open and more or less cup-shaped (called an "apothecium"), closed and spherical in shape (called a "cleistothecium"), or flask shaped, with a small pore through which the ascospores escape (called a "perithecium"). The layer of asci is called the hymenium", or hymeneal layer, which lines the ascocarp. Figure 13: Some typical "ascocarps" found in the division Ascomycota. a) Sexual Life Cycle of Ascomycota Figure 14 illustrates a typical life cycle of Ascomycota. When examining the slides and preserved materials in this lab, try to place it into this generalized life cycle. The mycelium is initiated with the germination of an ascospore, or conidium. Many "crops" of conidia are produced during the growing season, and it is the conidia that are responsible for propagation of the fungus. Asci formation occurs on the same mycelia that produce conidia. They are preceded by the formation of multinucleate gametangia called "antheridia" and "ascogonia". The male nuclei of the antheridium pass into the ascogonium via a tubular outgrowth of the ascogonium known as the trichogyne. "Plasmogamy", or the fusion of the two cytoplasms, has now taken place. The male nuclei then pair with the genetically different female nuclei within the common cytoplasm but do not fuse. Hyphae now begin to grow out of the ascogonium. As the hyphae develop, pairs of nuclei migrate into them and simultaneous mitotic divisions occur in the hyphae and ascogonium. Cell division in the developing hyphae occurs in such ways that the resulting cells are "dikaryotic" (i.e. containing two haploid nuclei, one from each strain). The dikaryotic hyphae grow together to form a reproductive structure called an "ascocarp". The ascus first forms at the tip of the developing dikaryotic hypha. The two nuclei in the terminal cell (ascus) of the dikaryotic hyphae then fuse into a single diploid nucleus ("karyogamy"). This is the only zygote. The ascus then elongates and the diploid nucleus divides by meiosis, forming 4 haploid nuclei. Each haploid nucleus usually divides again by mitosis, resulting in a total of 8 haploid nuclei. These haploid nuclei are then cut off in segments of the cytoplasm to form "ascospores". In most Ascomycota, the ascus becomes turgid at maturity and finally bursts, sending its ascospores explosively into the air. Ascomycota. 3) Examples of Ascomycota Figure 14: Life Cycle of a Typical a) Yeast Yeast are somewhat atypical of most Ascomycota. They are predominantly unicellular and reproduce asexually by fission or by budding (pinching-off of small buds), rather than by spore or conidia formation. Sexual reproduction in yeasts occurs when either two cells or two ascospores unite and from a diploid zygote. The zygote may produce asexual buds, or may undergo meiosis to produce four haploid nuclei. In some species there may also be a subsequent mitotic division producing eight haploid nuclei. The single cell in these unicellular yeasts is acting as an ascus, and therefore the whole organism becomes the reproductive structure. Within the ascus/zygote wall, walls are laid down around the nuclei so that eight ascospores are formed. These are liberated when the ascus wall breaks down. The ascospores either bud asexually or fuse with another cell to repeat the sexual process. Two genera of yeasts, Saccharomyces sp. and Schizosaccharomyces sp. are commonly used in the baking and brewing industry. In both these genera the asci are formed by the fusion of two haploid cells. Note the presence of 4 ascospores in each ascus. Also note that in these unicellular yeasts, there is no "ascocarp". Figure 15 shows yeast cells in various stages of asexual and sexual reproduction. Figure 15: Yeast cells budding and sporulating. b) Penicillium sp. (blue - green molds) Penicillium sp. has become celebrated in connection with antibiotics. Penicillin, a by-product of Penicillium notatum when liberated into the culture medium, inhibits the growth of gram-positive bacteria. Penicillin was discovered by Sir Alexander Fleming in 1929, but was not exploited until World War II. The great importance of this substance is that it represses bacterial growth without being toxic to animal tissues. Interest in penicillin led to an intensive search for other antibiotics, and molds suddenly became of considerable economic interest. However, Penicillium sp. is of economic importance in other respects. For example certain species give some types of cheese the flavor, odor, and character so highly prized by gourmets. One such mold, P. roquefortii, was first found in caves near the French village of Roquefort. Legend has it that a peasant boy left his lunch, a fresh piece of mild cheese, in one of these caves and on returning several weeks later found it marbled, tart, and fragrant. Only cheeses from the area around these particular caves are permitted to bear the name of Roquefort. Another species of this genus, P. camembertii, give Camembert cheese its special qualities. Penicillium sp. reproduces asexually by forming spores called conidia. Penicillium sp. conidiophores and conidia. c) Cup Fungi The cup fungi are the most advanced group of Ascomycota. They produce an ascocarp called an "apothecium", with the asci arranged in an exposed layer. Although many apothecia are disc or cup-shaped, other forms also exist. Peziza sp. The apothecia of Peziza sp. often exceed 10 cm in diameter. These apothecia are usually bowl-shaped when young but will become flattened and distorted with age. At maturity, the thousands of asci on the surface of the cup develop hydrostatic pressure. If the cup is disturbed, the asci rupture releasing thousands of ascospores in a visible "puff". Wind currents then transport the spores to a new environment. Figure 17: Diagram of the apothecium of Peziza sp. (top) and microscopic view of asci (bottom). Morchella sp. (morels) These are some of the most highly prized edible fungi. The apothecium of Morchella sp. has a stalk, or stipe, and a fertile portion called the "pileus" (Figure 18). The pileus is essentially discoid, but it is folded over the stipe apex and is highly contorted. These distortions greatly increase the surface area of the pileus. The asci line the large pits, which are separated by sterile ridges. Each "pit" is similar to the cup of Peziza sp. In other words, each pit is an apothecium producing ascospores. Morchella sp. Diagram (left) and picture (right) of the apothecia of Morchella sp. Morchella sp. C) Division (Phylum): Basidiomycota The most familiar of all fungi are members of this large sub-division. It includes some 25,000 described species, not only the mushrooms, toadstools, stinkhorns, puffballs, and shelf fungi but also two important plant pathogens: the rusts and smuts. The Basidiomycota are distinguished from all other fungi by the production of basidiospores, which are borne outside a club-shaped, spore-producing structure called the basidium (plural, basidia).The basidia are produced by basidiocarps, which are the fruiting bodies of the so-called higher fungi, such as mushrooms and puffballs. Basidiocarps, like the ascocarps, are the large fruiting structures, which are the most visible stage of the fungus. A typical mushroom is a familiar example of a basidiocarp. 1) Life Cycle of Basidiomycota The mycelium of the Basidiomycota is always septate and in most species passes through three distinct phases -primary, secondary, and tertiary- during the life cycle of the fungus. When it germinates, a basidiospore produces the primary mycelium. Initially the mycelium may be multinucleate, but septa soon form and the mycelium is divided into monokaryotic (uninucleate) cells. This septate mycelium grows by division of the terminal cell. Branches do occur, and the mycelial mass can become very complex. Commonly the secondary mycelium is produced by the fusion of primary mycelium from two different mating types (plasmogamy) [Figure 19]. The tertiary mycelium, which is also dikaryotic, arises directly from the secondary mycelium, and forms the basidiocarp. The spore forming basidia are produced by the terminal cell on millions of dikaryotic hyphae. In a typical mushroom, basidia are found on gills, under the cup (Figure 20A). Karyogamy occurs between the two haploid nuclei within a developing basidium. Then, the diploid nucleus undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid nuclei. These nuclei then migrate into four small extensions at the apical end of the basidium, and are walled off to form the four basidiospores. Figure 19: Life Cycle of Typical Basidiomycota. 2) Examples of Basidiomycota a) Gilled Mushrooms. The basidiocarps of this group are large and conspicuous. They are the familiar mushrooms and toadstools. The vegetative portion of the fungus exists as a mycelial network, which grows saprobically beneath the substrate, often as mycorrhizae with trees. The basidia are borne in a layer on the surface of "gills" which, in turn, are produced on the underside of fleshy umbrella-like basidiocarps. The basidiospores are forcibly ejected form the basidium. The basidiocarp consists of a stout stalk (stipe) bearing a circular cap (pileus) from which the lamellae (gills) hang down (Figure 20). Most members of this order are saprobic but some are tree parasites. It should be recognized that in the Agricales, the fruiting body (basidiocarp) is an ephemeral structure usually lasting only a few days, whereas the mycelium, living on organic matter in the soil, may last for years. Figure 20A: Diagram of a Basidiocarp. Figure 20B: Basidiocarp of Coprinus comatus (inky cap mushrooms). Another Coprinus sp. - "Shagy mane". These mushrooms are the deadly Amanita musaria var. muscaria commonly called Fly Agaric. It is deadly poisonous! Don't Eat. Note the gills, layers of basidia, and basidiospores (Figure 21). Gills x.s. Gills x.s. close-up. Basidium and basidiospores close-up. Figure 21: Microscopic view of cross-section through the gills of the basidiocarp. b) Bracket Fungi Members of this diverse group of fungi produce basidiocarps that are woody, leathery or papery but never soft. The basidia are found covering the surface of gills, or "teeth", or lining the inside of "pores". Many of the common "bracket fungi" or shelf fungi, found growing on the surface of living or dead tree trunks, are members of this group (Figure 22). Figure 22: Some members of the bracket fungi. c) Puffballs and Earth Stars In the puffballs, the mature basidiocarp consists of a papery outer covering with a small opening or "ostiole" on the top. Inside is the mass of spores. When raindrops strike the leathery covering, "puffs" of spores are ejected through the ostiole (Figure 23). Note the demonstration material of puffballs (Figure 24) and earthstars (Figure 25). Remember the structure you see is a basidiocarp similar to that of a mushroom. Figure 23: Young and mature basidiocarps. Figure 24: Lycoperdon sp. (puffballs). Figure 25: Geaster sp. (earthstars).