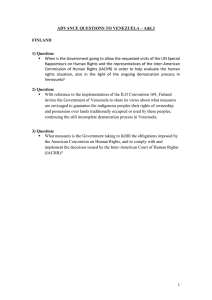

Mapping Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a

advertisement