A Advance Version Human Rights Council

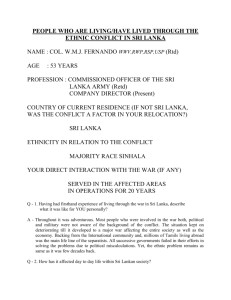

advertisement