RISING POWERS PROGRAMME first approach”

RISING POWERS PROGRAMME

“Popular responses to income inequality in China and Russia: a qualitative first approach”

Neil Munro, University of Glasgow

European Consortium for Political Research

Annual Conference , Glasgow

6 September 2014

1

Issues

Why do Chinese and Russians accept or reject, approve or disapprove, tolerate or refuse to tolerate income inequality and the wealth gap?

What are the implications for political research?

2

Argument

• The apparent contradiction between strong support for equity-based norms and broad dissatisfaction with distributive processes and outcomes reflects neglect in the literature of what goes on between the ideal and real world economies.

3

Key arguments in the literature

• Researchers distinguish between

– Support for equity, equality and need as distributive principles

– Endorsement of principles, processes and outcomes.

4

Russia’s trajectory

• Kluegel et al. (1999) found Russia in 1996 was diverging from CEE countries in direction of socialist principles.

• Perceived fairness (outcome, +) and corruption (process, -) influence regime support in Russia (Kluegel et al. 2004, Rose et al.2011)

5

China’s trajectory

• Whyte (2010) found Chinese to be supportive of equity & happy with distributive processes, hence rejects “myth of social volcano.” But effects of distributive outcomes on processes on regime support not measured in his study.

6

Approach

• qualitative analysis of seven focus group discussions carried out in provincial cities in Russia and China in 2013 using parallel discussion guides

• a review of the mainly quantitative evidence about attitudes to inequality in Russia and China.

• Two methods are intended to complement rather than compete with one another.

Qualitative data is needed to identify interesting questions

Quantitative data provides a great many answers,…but not all.

7

Focus group discussions

• So far analysed discussions in 7 (out of 22) midlevel cities in different parts of the two countries.

• In China: Luoyang and Changsha, in central China,

Mianyang in western China, and Guangzhou on the eastern seaboard.

– Most in last three cities had rural residence registration, and most in the first had urban residence registration, but all groups were mixed in this respect.

• From Russia, discussions held in Ufa, in the Urals,

Saratov on the Volga and Vladivostok, in the Far

East.

8

Stratification and fairness in China

• Mr Wang, a young entrepreneur in Guangzhou, gave a fairly clear analysis of the political aspects of stratification: two to three years after graduation, his school alumni met up for dinner, but a social gap was already apparent between rich and poor alumni. A couple of years later, when the event was repeated, the organisers tried to invite only those on about the same level as themselves. Mr Wang explicitly related the gap to processes of social stratification: instead of second generation officials (guan er dai), China now has third generation wealthy families, and these people have already consolidated political control, penetrating all parts of government, so that others cannot make inroads. He likened the political game to a football match where the referee is allowed to kick the ball and never gives himself a red or yellow card.

9

Social fairness and the Russian state

• As Vladimir, a mechanic in his fifties from Saratov, put it, the law applies to the people but not to those in power.

• In the same city, Elena, a bank worker in her thirties, felt the underlying problem was a lack of equality: whoever has more money is always seen to be in the right.

• Roman, a young lawyer, felt that Russian society is unfair because the law and the structure of power don’t work as intended.

10

What the quantitative studies show: distributions

• There has been a decline in support for principles of equity (reward for effort) in both Russia and China.

• Chinese are relatively satisfied with distributive processes (eg. equality of opportunity, attributions of wealth and poverty); Russians are less satisfied, though some indicators much improved since the mid-1990s.

• Large majorities in both Russia and China believe the wealth gap is too big, eg. 72 per cent in China and 90 per cent in Russia (in 2014) thought the gap was too big

11

What the quants show: relationships

• The fact that personal economic gains, particularly in relation to peers, and economic optimism drive perceived legitimacy of distributive processes and also equity-based norms partially validates the measures used in both Russia and China.

• However, extant studies don’t show a clear relationship between what people believe about distributive processes and what they think about normative principles of distribution.

• Either the theoretical expectation that positive beliefs about processes would lead to a preference for equitybased principles turned out to be too simplistic OR the measures don’t capture what they’re intended to.

12

What the FGDs suggest

• The implications of existing levels of inequality for social and political stability in the two societies are potentially quite serious.

• The problem is not so much that there are irreconcilable differences of principle on questions of distribution, though these continue to exist.

• Rather, there are two nagging problems:

– distribution in practice is seen to operate unfairly; rule breaking is too often rewarded;

– People are unhappy with the overall shape of income and wealth distribution: the gap between rich and poor is seen as “excessive.”

13

Implications for research

• The Russia and China literatures don’t offer any convincing explanations of how perceptions of distributive processes influence preferences for different normative principles.

• They fail to give an adequate account of the roles of perceived corruption, inequality of opportunity and the nature of stratification processes in shaping evaluations of distributive outcomes.

• There is a paucity of political explanations of attitudes to inequality, with most research failing to move beyond simplistic assumptions of self-interest (Kluegel et al. being an honourable exception).

• For China, there still isn’t an adequate understanding of how distributive processes and outcomes influence regime support.

14

Thank you!

Comments welcome to

Neil.Munro@glasgow.ac.uk

Internalization of social boundaries

• Nadezhda, a young professional woman living in

Vladivostok, thought that European societies were probably quite fair, if you ignored the “excessive” allowances

(loyal’nost’) they made for gays and immigrants.

• Ms Fei, a female worker in her forties living in Mianyang with a rural local hukou, noted how village cadres had somehow used their power to build businesses which allow them to get ahead (as shown by buying a house and car, and raising a family). By contrast, a migrant worker who had worked as hard or harder could not afford these things.

She felt the gap was particularly unfair because the cadres belonged to the same social category as “us”.

16

Equity, equality and opportunity

• In Mianyang, Ms Fei felt that policy ought to distinguish people according to how well they met social expectations. For example, a couple with two kids to put through high school, and one or more sick parents, each working their fingers to the bone to get 1000 or 2000 yuan per month as migrants in a distant city, were clearly “deserving.” It was not acceptable that they should be poor. But a single man without kids who couldn’t get a job was obviously “lazy” and undeserving of help.

• In Vladivostok, Maksim offered a fairly coherent version of a pro-market belief system. He was against redistribution of wealth because “we live in market conditions,” and if we try to “suffocate” market mechanisms, then,

“as shown by practice” nothing good will come of it. For that reason, he argued, responsibility for welfare should lie precisely on individuals, and if everyone did that for themselves and their families there would be no need for some “gigantic redistribution of wealth.” Maksim also felt that the market had not had the chance to show itself to best effect in Russia, in particular how it could help resolve social problems.

17

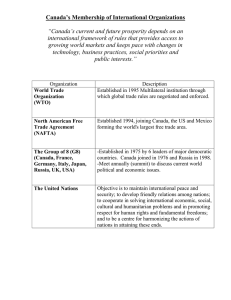

Table 1. Support for income differences as incentives in China and Russia

Q1. How would you place your views on this scale? 1 means you agree completely with the statement on the left;

10 means you agree completely with the statement on the right; and if your views fall somewhere in between, you can choose any number in between. Incomes should be made more equal vs We need larger income differences as incentives. (HIGHER VALUES: more tolerant of income inequality)

China Russia China-Russia

1990

1995

2001

2007 a

2012 a

Mean (standard deviation)

7.87 (2.32)

5.04 (3.15)

6.26 (3.11)

5.77 (3.10)

3.99 (3.01)

6.99 (2.52)

6.46 (2.77)

Na

6.40 (3.38)

2.98 (2.85)

Trend -3.88*** -4.01*** a Russia: 2006, 2011; *** significant at .001 level; na: not available.

Difference

0.88 ***

-1.42 ***

-.63 ***

1.09 ***

Sources: Q1: World Values Surveys Waves 2-6, China: 1990 (N=1000), 1995 (N=1500), 2001 (N=1000), 2007

(N=2015), 2012 (N=2300); Russia : 1990 (N=1961), 1995 (N=2040), 2006 (N=2033), 2011 (N=2500).

18

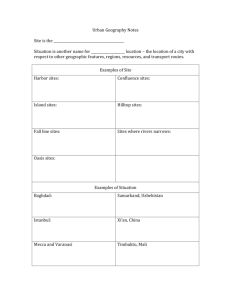

Table 2. Evaluations of the size of the income gap in China and Russia

Q1. What do you think about the difference in incomes people have in this country? Are the differences much

too large, somewhat too large, about right, somewhat too small or much too small?*Ϯ

China 2004

Much too large 40

Somewhat too large 32

About right 23

Somewhat too small 4

Much too small 1

8

9

6

39

38

Russia

1991 1996 2007Ϯ 2014* Trend **

61

31

82

11

59

31

+17

-9

7

1

0

5

2

Na

Na

8

2

-1

-4

Na

-3

-1

China-Russia

Difference**

-7

11

Na: not asked.

Ϯ In 2007: Do you think that the gap in incomes between rich and poor is now: less than it should be, as it should be, wide but acceptable, or excessively wide?

* In 2014: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the statement that differences in income in Russia are too large? Entirely agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, entirely disagree.

**calculated by excluding “about right” from the 1991 distribution.

Sources: International Social Justice Programme Survey in Russia, autumn 1991 (N=1734) and June 1996

(N=1585), as detailed in Stephenson & Khakhulina 2000, p.85; New Russia Barometer XVI, December 2007

(N=1601), as detailed in Rose, 2008, p.35; University of Glasgow & ANU Russia Survey, 25 Jan-17 Feb 2014

(N=1602), B11; China National Survey on Perceptions of Distributive Justice, autumn-winter 2004 (N=3267), as detailed in Whyte 2010, p.44

19

Supplementary Table. Support for reward of individual achievement in China and Russia

Q2. On this card you will find a set of contrasting opinions about public problems. Please say which alternative you agree with, whether strongly or somewhat. (% agree)

Incomes should be made more equal, so there is no great difference in pay

China 2012-13 Russia

Definitely

Somewhat

25

34

1996*

13

15

2005* 2014 Trend

20 22 +9

26 28 +13

Income differences should depend only on individual achievement.

China-Russia

Difference

+3

+6

Somewhat

Definitely

29

12

22

50

14

40

28

22

+6

-28

* Definitely asked first for each alternative

Sources: New Russia Barometer VI , July-Aug 1996 (N=1599), XIV, Jan. 2005(N=2069), PETU Health Care in China

+1

-10 survey, Nov 2012-Jan.2013 (N=3680); U. Glasgow & ANU Russia Survey, Jan-Feb 2014 (N=1602).

20