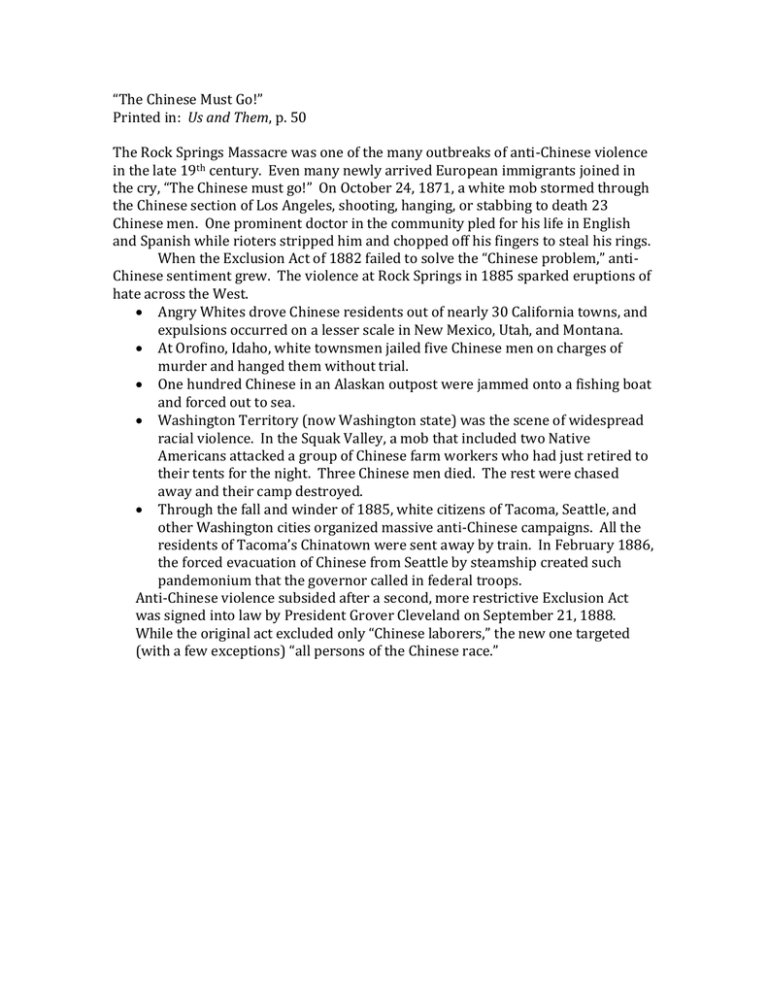

“The Chinese Must Go!” Us and Them

advertisement

“The Chinese Must Go!” Printed in: Us and Them, p. 50 The Rock Springs Massacre was one of the many outbreaks of anti-Chinese violence in the late 19th century. Even many newly arrived European immigrants joined in the cry, “The Chinese must go!” On October 24, 1871, a white mob stormed through the Chinese section of Los Angeles, shooting, hanging, or stabbing to death 23 Chinese men. One prominent doctor in the community pled for his life in English and Spanish while rioters stripped him and chopped off his fingers to steal his rings. When the Exclusion Act of 1882 failed to solve the “Chinese problem,” antiChinese sentiment grew. The violence at Rock Springs in 1885 sparked eruptions of hate across the West. Angry Whites drove Chinese residents out of nearly 30 California towns, and expulsions occurred on a lesser scale in New Mexico, Utah, and Montana. At Orofino, Idaho, white townsmen jailed five Chinese men on charges of murder and hanged them without trial. One hundred Chinese in an Alaskan outpost were jammed onto a fishing boat and forced out to sea. Washington Territory (now Washington state) was the scene of widespread racial violence. In the Squak Valley, a mob that included two Native Americans attacked a group of Chinese farm workers who had just retired to their tents for the night. Three Chinese men died. The rest were chased away and their camp destroyed. Through the fall and winder of 1885, white citizens of Tacoma, Seattle, and other Washington cities organized massive anti-Chinese campaigns. All the residents of Tacoma’s Chinatown were sent away by train. In February 1886, the forced evacuation of Chinese from Seattle by steamship created such pandemonium that the governor called in federal troops. Anti-Chinese violence subsided after a second, more restrictive Exclusion Act was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland on September 21, 1888. While the original act excluded only “Chinese laborers,” the new one targeted (with a few exceptions) “all persons of the Chinese race.” “Targeting Undocumented Immigrants” Printed in: Us and Them, p. 42 In February 2004, Domingo Lopez Vargas was leaving a grocery store in Canton, Georgia, when four white teenagers in a pickup truck offered him work at $9 an hour. The day laborer, originally from Guatemala, accepted. The young men drove Vargas to a remote field and then pummeled him with pieces of wood for half an hour, leaving him bloodied from his thighs to his neck. The attack was part of a growing pattern of violence against low-income, immigrant, day-laborers. Attackers lure their victims with promises of work and then assault and rob them. In many cases, the attackers are teenage boys. The tensions rose amid a rapid demographic shift and public animosity toward undocumented immigration. Between 1990 and 2005, 1 million Latino immigrants moved to Georgia – an increase of 300 percent. In the first few years of the new millennium, Georgia had the fastest growing Latino population in the country. Jobs – usually accompanied by long hours and few protections – draw immigrant workers here, typically in construction, manufacturing, agriculture, and forestry. While many of these industries have been dominated by immigrant labor in the past, the noticeable growth in the Latino population caused many nonimmigrants to complain that undocumented immigrants were stealing jobs that should go to U.S. citizens. Immigration into other Southeaster states has generated low-level controversy and occasional outbursts of anti-immigration rhetoric. The allegations always sound familiar: higher crime rates, littered streets, gang activity, millions spend on health care and education for “illegals.” But the backlash in Georgia has been unusually fierce, turning the state into an epicenter for radical anti-immigration activism. Much of the focus has been on undocumented immigrants, seen as an unnecessary strain on the state’s fiscal and social resources. Day laborers like Domingo Vagas have become easy targets. Unlike their counterparts in the fields and poultry plants of rural Georgia, they are more visible, waiting for work every morning in urban centers. The anti-immigration sentiment behind Vargas’ attack also is seeping into state law: A bill passed by the Georgia legislature in March 2006 would make it a crime to provide certain social services to undocumented immigrants. But immigrants – including those who risk deportation – are fighting back against the hate and injustice. In April 2006, at least 50,000 immigrants and their allies hit the streets of Atlanta as part of a massive wave of peaceful demonstrations sweeping the country. The message on many signs in the crowd was clear: “No human is illegal.”