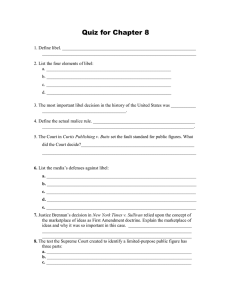

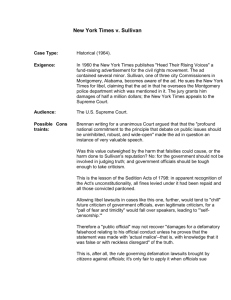

New York Times Company v. Sullivan 1964

advertisement

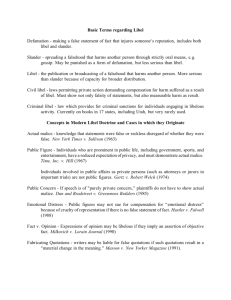

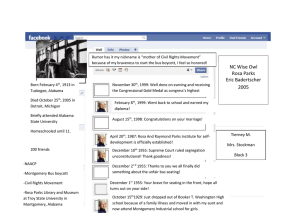

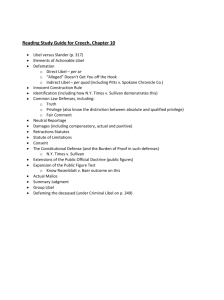

New York Times Company v. Sullivan 1964 Appellant: The New York Times Company Appellee: L. B. Sullivan Appellant's Claim: That when the Supreme Court of Alabama upheld a libel judgment against The New York Times, it violated the newspaper's free speech and due process rights. Also, that an advertisement published in the Times was not libelous. Chief Lawyers for Appellant: Herbert Brownell, Thomas F. Daly, and Herbert Wechsler Chief Lawyers for Appellee: Sam Rice Baker, M. Roland Nachman, Jr., and Robert E. Steiner III Justices for the Court: Hugo Lafayette Black, William J. Brennan, Jr. (writing for the Court), Tom C. Clark, William O. Douglas, Arthur Goldberg, John Marshall Harlan II, Potter Stewart, Earl Warren, and Byron R. White Justices Dissenting: None Date of Decision: March 9, 1964 Decision: The Alabama courts' decisions were reversed. Significance: The U.S. Supreme Court greatly expanded Constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and the press. It halted the rights of states to award damages in libel suits according to state laws. On March 23, 1960, an organization called the "Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South" paid The New York Times to publish a full-page advertisement. The ad called for public support and money to defend Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. who was struggling to gain equal rights for African Americans. The ad ran in the March 29, 1960 edition of the Times with the title "Heed Their Rising Voices" in large, bold print. The ad criticized several southern areas, including the city of Montgomery, Alabama, for breaking up civil rights demonstrations. In addition, the ad declared that "Southern violators of the Constitution" were determined to destroy King and his civil rights movement. No person was mentioned by name. The reference was to the entire South, not just to Montgomery or other specific cities. ACTUAL MALICE STANDARDS Until 1964, each state used its own standards to determine what was considered libelous. This changed after the decision in New York Times Company v. Sullivan. This landmark case established the criteria that would be used nationwide when determining libel cases involving public officials. The Court stated that "actual malice" must be shown by the publishers of alleged libelous materia, when the falseness of the material is proven. This standard was later broadened by the Supreme Court to include not only public officials, but also "public figures." This includes well-known individuals outside of public office who receive media attention, such as athletes, writers, entertainers, and others who have celebrity status. Sullivan sues Over 600,000 copies of the March 29, 1960 Times edition with the ad were printed. Only a couple hundred went to Alabama subscribers. Montgomery City Commissioner L. B. Sullivan learned of the ad through an editorial in a local newspaper. On April 19, 1960, an angry Sullivan sued the Times for libel (an attack against a person's reputation) in the Circuit Court of Montgomery County, Alabama. He claimed that the ad's reference to Montgomery and to "Southern violators of the Constitution" had the effect of defaming him, meaning attacking and abusing his reputation. He demanded $500,000 in compensation for damages. On November 3, 1960, the Circuit Court found the Times guilty. The court awarded Sullivan the full $500,000 for damages. The Alabama Supreme Court upheld the Circuit Court judgment on August 30, 1962. In its opinion, or written decision, the Alabama Supreme Court gave an extremely broad definition of libel. The opinion stated that libel occurs when printed words: injure a person's reputation, profession, trade, or business; accuse a person of a punishable offense; or bring public contempt upon a person. Supreme Court protects the press The Times's chief lawyers took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. On January 6, 1964, the two sides appeared at a hearing before the Court in Washington, D.C. On March 9, 1964, the Supreme Court unanimously (in total agreement) reversed the Alabama courts' decisions. The Court held, meaning decided, that Alabama libel law violated the Times's First Amendment rights to freedom of the press. The Court recognized what Alabama's own newspapers had written. The newspapers had reported that Alabama's libel law was a powerful tool in the hands of anti-civil rights officials. The Court's decision canceled out Alabama's overly general libel law so that it could no longer be used to threaten freedom of the press. Next, Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., stated that a new federal rule regarding libel law was needed. The new rule stopped a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood, or lie, about his official conduct unless he proved that the statement was made with actual malice (ill will). Sullivan had not proven that the Times had acted with actual malice. What is actual malice? The Court defined it as knowingly printing false information or printing it "with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not." Court broadens freedom of speech and press In libel suits after New York Times Company v. Sullivan, the Court continued to expand the First Amendment's protection of freedom of speech and press. The Court decided that for any "public figure" to sue for libel MONTGOMERY DEMONSTRATIONS Montgomery was the site of a lot of civil rights activity, largely because of the events set off by Rosa Parks. In 1955, Parks, then a forty-three-year-old seamstress working at a Montgomery department store, was on her way home from work. At that time, Montgomery city buses were segregated. Whites sat up front, blacks sat in the back. When Parks could not find a seat in the back, she sat in the middle of the bus. The driver told her to move to make room for new white passengers. Parks refused—and was arrested. Parks had been a civil rights activist for some time, working with the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Now she worked with local civil rights leaders who decided to use her case to end segregation on public transportation. Parks's pastor, the twenty-seven-year-old Martin Luther King Jr., led a boycott of Montgomery city buses. (A boycott is a refusal to buy, use, or sell a thing or service.) Local officials bitterly resisted the boycott. Police arrested Parks a second time for refusing to pay her fine. They also arrested King. First on a drunkdriving charge, and then for conspiring (secretly planning) to organize an illegal boycott. The boycott of the city buses lasted for over a year. It ended with the November 1956 Supreme Court decision against the bus segregation. Montgomery continued to be a center of civil rights activity throughout the early 1960s and win, she or he would have to prove "actual malice." Public figures include anyone widely known in the community, such as athletes, writers, entertainers, and others with celebrity status. Also, the requirement for actual malice protects anyone accused of libel, not just newspapers like the Times. The Sullivan case was a huge advance for freedom of speech. It prevented genuine criticism from being silenced by the threat of damaging and expensive libel lawsuits. Sullivan has not, however, become a license for the newspapers to print anything that they want to print. Defendants who act with ill will can receive severe penalties. http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3457000047&v=2.1&u=brem18020&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=7 18924cf8317a0af89b2c59a27da780c

![Think Like an Editor [Spoken libel is slander.] Strategy 31—Libel](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015585784_1-4a4df9f403a1d41970830c08b388ca3a-300x300.png)