Frankenstein – Mary Shelley Author Biography

advertisement

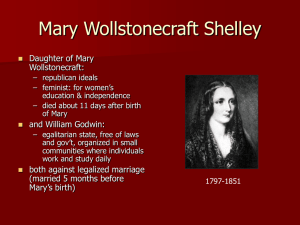

Frankenstein – Mary Shelley Author Biography Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, née Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, was the only daughter of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. Their high expectations of her future are, perhaps, indicated by their blessing her upon her birth with both their names. She was born on 30 August 1797 in London. The labor was not difficult, but complications developed with the afterbirth. Despite expert attention, her mother sickened from placental infection and died eleven days after her birth, on 10 September. Mary was brought up with her elder sister Fanny Godwin, the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft and her American lover Gilbert Imlay, who was adopted by Godwin and reared as his own child until the age of eleven when he disclosed her parentage to her. The family complications were considerably advanced in 1801 with Godwin's remarriage to his neighbor, the widowed Mary Jane Clairmont, which brought two further children, Charles and Claire Clairmont, into the household. A fifth sibling was added in 1803 with the birth of William Godwin, Jr. The five children were instructed principally at home. Following Godwin's own precepts, there was little distinction made in their educations on the basis of sex, so Mary Godwin had an education of considerable breadth, one that few girls in her age could equal. Apart from formal instruction, the children were exposed almost daily to Godwin's extensive acquaintance among the London intelligentsia, ranging from the poet and philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whom Mary heard recite "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" in Godwin's living room, to scientists like Humphry Davy and her father's bosom friend William Nicholson, the two foremost experimenters with galvanic electricity in the early years of the nineteenth century. These figures especially would later have a noticeable impact on the writing of Frankenstein. As heady as this intellectual climate was, there was a practical side to Mary's education in the Godwin-Clairmont household as well, for its income derived mainly from the proceeds of the Juvenile Library, their publishing venture specializing in books of instruction for younger readers. At the age of ten Mary had her first experience with publication, when the Juvenile Library printed her witty poem, Mounseer Nongtongpaw; or, The Discoveries of John Bull in a Trip to Paris. By 1812 it was in a fourth edition. That same year, at the age of fourteen, Mary was exposed to yet another broadening influence, when, in order to distance her from the step-mother she resented and disliked, Godwin sent her on an extended visit to the Baxter family in Dundee, Scotland. There she resided from June to November of 1812 and, again, from June 1813 to March of 1814, developing a strong attachment to the Baxter's adolescent daughter Isabel, who became her first close friend. Shortly after her return to the family home, she became reacquainted with her father's youthful admirer, Percy Bysshe Shelley, whom she had first met in the company of his wife Harriet in late 1812. Now, he became a frequent visitor to the Godwin household, and the two of them fell in love. In July, with Mary still in her sixteenth year, the couple eloped to the continent accompanied by Mary's stepsister Claire. It is perhaps to be expected that this couple, immersed as they were in the world of books, would turn the journal of their elopement into a travel book, which Mary wrote up and published as History of a Six Weeks' Tour in 1817, while her first novel was being prepared for the press. The conjunction of the works suggests a self-assured young writer assuming a professional identity. The young woman who returned in September of 1814 from her two-month tour, however, was not yet ready for such a role. The couple was penniless, and Shelley was forced to hide from creditors; Godwin, feeling injured by his daughter, would not even see her lover; and Mary, unmarried and barely seventeen, was pregnant. To aggravate this sense of a sudden and severe constriction of opportunity, Mary's friend Isabel Baxter was forced by her family to terminate their acquaintance. Years later, upon her return to England from Italy as Shelley's widow, Mary found herself regularly refused the notice of respectable people who would never forgive her, whatever her subsequent career, for so blatant a transgression of proper social decorum. Over the next two years Shelley fashioned a financial stability for them (and for William Godwin, even though he would still not speak to him), and the couple developed a circle of friends. Mary was twice pregnant, losing her first child, a daughter, after three weeks, but giving birth to a son, named after her father, in January 1816. In retrospect, she would idealize these years spent near Windsor, where she sets the early chapters of her third novel, The Last Man (1826). Still, she was as yet unmarried and had yet to accomplish anything on her own. The impetus to a new chapter in her life was provided inadvertently by her step-sister. Claire, who tended to compete with Mary, in a bizarre but successful scheme set out to secure her own poet-lover, and she hit on the chief prize, Lord Byron, whose separation proceedings from his wife formed the prime scandal of the 1815-16 winter. By the spring Byron had set off for exile on the continent, and Claire found herself pregnant. Claire, needing to establish the paternity of the expected child, confided in Mary, who, in turn, convinced Shelley of the importance of this claim. So came about the famous summer of 1816 on the shore of Lake Geneva. Mary has left her own account of this period in the Introduction she supplied to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein. What she does not quite get around to saying in that dignified memoir is that Claire did, indeed, establish Byron's care for his future child, though with the unexpected and rather unpleasant proviso that he never again see the mother; that Shelley made the acquaintance of, and then developed a particularly intense intellectual friendship with, the foremost poet of the age; and that, amidst all these heady events and with almost no one but herself noticing, she quietly became a writer and set out on her remarkable career. Upon her return to England in September of 1816, Mary quickly began to develop the novel she had started in the summer. Its progress was twice interrupted by family catastrophe, first the suicide of her half-sister Fanny in October, then the discovery in December of the body of Harriet Shelley, who, being with child, had herself committed suicide the month before. Two weeks after they were notified of Harriet's suicide, on 30 December 1816, Mary Godwin and Percy Bysshe Shelley were married. This event brought about an immediate reconciliation with Godwin, but was attended as well by a lawsuit in the Court of Chancery brought by Harriet's family with the intention of depriving the father of custody of his two children from the marriage. The success of this suit convinced Shelley and Mary that they would suffer continual persecution if they remained in England. On the first day of 1818Frankenstein was published anonymously, followed shortly after by Shelley's book-length narrative poem, The Revolt of Islam. On 12 March Mary and Shelley, with their two children Clara and William, along with Claire and her daughter Allegra, departed from England to make a new home in Italy. The four years they spent in Italy saw the establishment of Percy Bysshe Shelley as one of the foremost poets in the English language. It likewise furthered the career of Mary Shelley as "The Author of Frankenstein," the rubric under which she continued her anonymous publication with a second novel immersed in medieval Italian history, Valperga: or, The Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca (1823). After Percy Bysshe Shelley's death by drowning in 1822, Mary Shelley found herself without sufficient financial means to remain in Italy and, with some reluctance, returned to England to begin a second existence there in the fall of 1823. She never equalled the popular success of Frankenstein, but she published a number of other novels after Valperga: The Last Man (1826), The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830), Lodore (1835), andFalkner (1837). In addition to her novels, she produced a large volume of miscellaneous prose: short stories, biographies, and travel writings, including the retrospective Rambles in Italy and Germany of 1844. She likewise supervised the publication of her husband's Posthumous Poems, which appeared in 1824, his Poetical Works (1839), and his prose (1839 and 1840). Her only surviving child was Percy Florence Shelley, who was born in 1819 and who acceded to the baronetcy upon the death of Shelley's father, Sir Timothy, in 1844. Mary Shelley herself died in her home in Chester Square, London, on 1 February 1851.